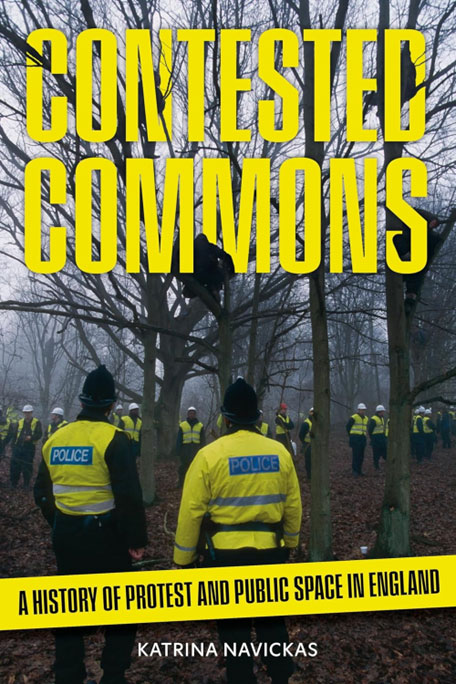

Contested Commons. A History of Protest and Public Space in England, Katrina Navickas (Reaktion Books)

Katrina Navickas waste no time in getting down to business. Her Introduction starts with this lucid declaration:

Protest is about claiming public space. The demonstration, the march

and the occupation are spatial forms of protest. Protestors enact

rights to meet, move and speak in public spaces. Public space is a

site of democratic performance, revolution and claim-making, where

the collective power of the people is manifested in action through the

occupation of squares and streets in marches and demonstrations.

But not so fast! Navickas immediately points out that public space is not always that public. Much of it is, and always has been, controlled by private companies, estates, landowners or businesses; most public land comes with rules about what you can do there and when you can do it. She considers the privatisation of many areas within cities, by the National Trust in their quest to maintain ‘heritage’, and how there was no ‘right to assembly’ until very recently.

It turns out that ‘the commons’ is a bit of a myth, is something that has never really existed. ‘Public space is a cultural understanding,’ she writes, ‘rather than a legal or economic reality’, a term with ‘no specific definition in English law or legislation.’ Landowners have always controlled where and how the peasants lived and farmed, wealth has always been accrued by those already wealthy, and there has never been much consideration for general wellbeing, health or leisure. Land ownership is an expression of power and money, with control of access just as important as control of production.

Navickas’ introduction points out that the imbalance between classes and their access to land was highlighted during the Covid lockdown, before the book proper starts proper with some history, both recent and more distant, gradually meandering towards the present in the final chapter. Time and again she highlights how specific spaces have been used for social and/or political ends, and how various legal games and new legislation, have tried to interfere with this, usually hand-in-hand with brutal intervention by the police or armed forces.

This is not new, it is just that social media and live news can draw more attention to it. Or alternative newspapers and zines back in the day. The Greenham Common protestors were finally evicted by declaring that the road verges on the ‘public’ side of the airbase fence were, along with the whole of the Common, owned and controlled by the armed forces and that those camping were trespassers. In a similar manner, razor wire, temporary road closures and police thuggery resulted in the Battle of the Beanfield near Stonehenge, in an operation to stop the Stonehenge Festival. Similar actions were previously undertaken to stop the Windsor Free Festival, raves and the traveller community.

There was little regard for the fact that peace camps and free festivals produced little damage or aggravation beyond temporary loud music and clogged roads, nor that laws that affected the New Age travellers also affected the Romanies and other nomadic groups. Middle and upper class England were aghast at hippies, rusty vans, body piercings, dance music and the great unwashed, and wanted them gone. NIMBIES one and all: out of sight, out of mind. And a little (or lot) of blood and broken bones wasn’t a problem.

Elsewhere in the book there are discussions of squatting and the occupation of empty houses and streets awaiting demolition and redevelopment, Reclaim the Streets, adventure playgrounds, the sus law, political and anti-war demonstrations, the miners’ strike, the poll-tax and other riots, Occupy and the gradual clamping down on demonstrations and marches. The police started arming themselves and using kettling as well as aggressive dispersal and holding techniques, whilst squatting became a criminal activity and any more than 20, and later ten, people gathered together could be arrested if they were likely to cause a nuisance.

Navickas has examples from all over England (Scotland has different laws about access; she says she doesn’t want to speak for Wales) that mostly show a political disregard for ‘the public’, but it’s not all bad news. There are many instances here of successful negotiation and also of intervention by left-leaning politicians or business people who want to work with people rather than against them. These didn’t, of course, stop land being fenced or walled off, bought or patrolled by private security; nor the introduction of entrance fees to many heritage and landscape sites.

There are clearly many questions still to be asked about ‘public space’, not least why England is so scared of adopting the Scottish system of free access. I’d also like to know how, if the ‘commons’ is a myth, the campaign to save the Undercroft skatepark at London’s South Bank worked. My understanding is that continuous use for several decades meant it could be declared a village green or public commons, which is why the campaign was successful.

Reaktion are becoming experts in producing highly readable non-fiction books for the general reader, and Contested Commons is no exception. Although Navickas points out that we ‘should be cautious not to romanticize publicly owned public space, or to celebrate an accessibility or inclusivity that never was’ she also suggests that ‘we all need to actively participate, as citizens, to resist re-enclosure and dispossession of our human rights and those of the marginalized.’ Too bloody right.

.

Rupert Loydell

.