By Leon Horton

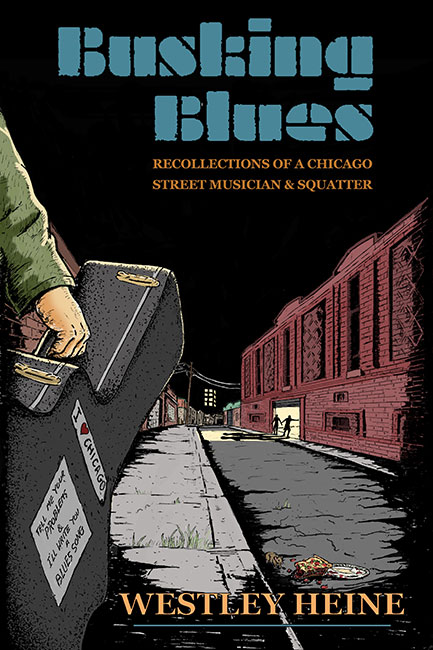

At the height of the recession, a singer-songwriter throws himself at the mercy of the Chicago streets in a class menagerie of workers, graffiti artists, hipsters, hustlers, punks, drunks, poets, grifters, and gangsters. Down but not out on the frontlines of modern America, Westley Heine’s freewheeling novel Busking Blues: Recollections of a Chicago Street Musician & Squatter hits like a shot of neon blue morphine icing through your veins. Provocative and visceral, this book will make your teeth curl and your hair bleed.

Westley Heine is the author of 12 Chicago Cabbies and The Trail of Quetzalcoatl. His poetry and prose has been published in The Chicago Reader, Gravitas, Heroin Love Songs, Beatdom, Dumpster Fire Press, Gasconade, and The Wellington Street Review. Life is always creating new characters inside him, but he is always a writer. To paraphrase Oscar Wilde: We are all in the gutter, but Westley Heine is staring at the curb. He grew up in Wisconsin, was lost and found in Chicago, married in Texas, and now resides in Los Angeles. Leon Horton steals a quart of whiskey and listens to the music…

Wes, your new novel Busking Blues was only recently published by Roadside Press and is already garnering some excellent reviews. Ron Whitehead, U.S. National Beat Poet Laureate no less, described it as “a broke down history of the blues. Ain’t no other map of Chicago like this one.” Dan Denton, author of 1000-A-Week Motel, proclaimed it “the underground indie hit of the summer,” and some hack from the UK charged that the book “eviscerates the Chicago streets with a rusty knife.” I’m quite proud of that last one, though I haven’t a clue what I meant. Do you think these accolades are a fair summation of the novel?

Yeah, I’m honoured by the heavy reviews. But I think the book comes on more subtle, accessible. It begins upbeat, like an adventure story, but it will sneak up on you, rip your heart out and stomp on it. My favourite “characters” aren’t around anymore. They didn’t make it. So yeah, you and the poets caught the gritty essence. But it’s like the carnival. The pitchman at the gate is welcoming. It’s all glitter and wholesome bullshit. But what you find at the heart of the show is the Geek biting the head off a chicken. That’s the truth. That’s what people are secretly looking for: that Earthy truth; that mirror, distorted as it may be. They say even humans taste like chicken. Yum yum.

Actually, I have it on good authority that human flesh tastes like pork, but we won’t go there. For the benefit of the reader, how would you describe Busking Blues?

In Busking Blues I use the hook of my experiences as a street musician to muse on such basic existential matters: free will vs. determinism, superstition that living on luck breeds vs. rational scientific thought, race and inequality, capitalism, addiction, heartbreak, the purpose and limits of art, homelessness, crime, and just the plain facts of life – the blues.

A street musician lives on chance encounters. As a person who has a scientific worldview, I found it unsettling during the busking period because I found myself thinking in terms of luck, fate, karma – sometimes, downright superstition. One of the underlining themes I was grappling with in the book is the age-old philosophical problem of Free Will vs. Determinism. How much of what happens in life is fate or from pre-determined forces and how much is from one’s own free will/ mindset/ decisions? Through the first half of the book, I bring up the question; but brush off philosophical questions as basically pointless when one is just trying to survive day to day.

What led you to become a street musician?

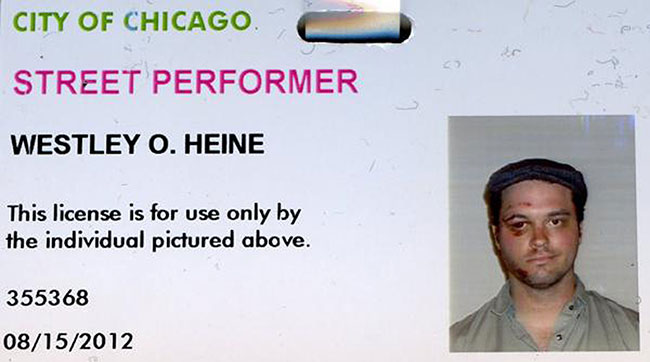

After graduating in 2007, as the Great Recession was dawning, I found myself working odd jobs and learning about real life rather than dream life. Chicago quickly kicked a lot of the Art School pretension out of me. After losing jobs, my car, and my mind due to a toxic relationship, by 2010 I decided to give up/go for it and become a street musician. This is where Busking Blues begins. It’s about giving up everything for the muse. Living on art and luck, my only concern was to get enough money each day for a meal.

Let’s get to the emotional crux of the book for a moment. What were you trying to achieve, creatively, when you volunteered yourself into the muttering gutter of the streets?

Creatively, I was expressing gritty realism, writing and singing stories about real life. The stories are about being poor, bad relationships, drinking in alleys… You can see the overlap with many of the Beat Generation’s subjects. Only, I write from the perspective of an ex 1990s garage band kid and a 2000s Art School nerd trying to keep his belly full. Maybe some things never change. Poetic writers always focus on eternal themes.

You served jail time in Wisconsin in 2002 for assaulting a fellow high school student after he sexually molested your then girlfriend. You have my utter respect for that. A criminal record can ruin a person’s life, but for a writer it can be a credential. Does your experience bear that out, or am I just being romantic?

I think you’re right. When it comes down to it, jail ain’t that different from a college dorm. Your roommate is in the way. It smells. The food is bad. A bit like joining the military. Thankfully, I had been accepted to an Art School in Chicago at the time. Based on this, the Judge let me out of jail after five weeks. My jail experiences and the characters are in a book called Little Rooms. I hope that one gets picked up next.

When did you first realize you wanted to be a writer?

It all starts with kid’s stuff: pretending, making up stories, playing army with your buddies in a cornfield, explaining crayon drawings of stickmen over a childhood lisp. Then, in adolescence, you have to deal with all these emotions and coming to terms with identity. Writing little rock songs, poems in spiral notebooks, drawings, making collages with magazines on bedroom walls help a kid figure out life. Back in high school I played in a metal band, did a lot of painting (including word-collage) and, most revealing, when I got my hands on Hunter S. Thompson’s Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas, I began writing, printing, and publishing my own gonzo newsletter where I would mock the news, and basically spread trouble and insanity throughout the school.

It wasn’t until college that I completely accepted the fact that I could say a lot more and say it faster with literature than with music or visual arts. I accepted this is where any talent I have actually resides. Of course, dabbling in other mediums informs the writing. One reviewer called Busking Blues a lyrical novel. I like that observation. Writing is this giant canvass where you can machinegun images, antidotes, ideas, dialogue, and character sketches into the imagination of a reader. When people find a book that speaks to them it usually cuts deeper than a film, a painting, and perhaps on par with music.

Do you work at a computer or write longhand?

I compose on the computer. If I’m travelling or out for the night and ideas attack me I will stuff my pockets with scribbles, scraps, notes – but those are just seeds to the actual work at the typer.

I find it interesting that you should use the word “compose” there. Are you still making music?

I’m not a musician who writes, I’m a writer who sometimes writes songs. Any new audio, I set free on YouTube under the Heaven’s Heartache project. I’m not Kerouac using words like jazz solos, but the pulse of the blues is under the lines somewhere. It’s more like what Henry Miller said at the beginning of Tropic of Cancer: “This is not a book… This then is a song. I am singing.” Meaning the new forms are open, sparse, poetic – a song unstrained by all the shit they force-feed you in English class.

Why do you write?

Everyone has something to contribute in this imperfect world. Some can fix a car, do your taxes, draw, perform a heart transplant, whatever. So many people have trouble finding the right words to articulate how they feel. When a person has an ear for words and can capture the ethos or a certain sensibility in writing, then everyone with those feelings finds a voice and finds some words. Perhaps those with a different sensibility will find empathy by seeing the world through a different point of view. But let’s get real: I’ve been typing prose and poems for twenty years and only recently have been getting published regularly. There is a reason I’ve been doing it beyond any philanthropic ideals. Any benefits to society from writing are a side effect of the original impulse. The real reason I write is for my own sanity, vanity, to scream in the dark, “Hey, this really happened. If no one reads about this, why did it even happen?”

Busking Blues is a confessional novel in many ways – at times, it reads like a psychiatrist’s wet dream, and for you most of those events are real. Is writing purging?

Is the cure for the blues the blues? I find writing therapeutic, but only to a certain extent. If your goal is to purge your demons with writing, I’d advise you to write it all out, read it to yourself once or twice and then burn that shit. If the goal is to write more professionally, you will quickly find out you aren’t cleansing yourself of the past but wallowing in your own bathwater. This was the main theme of my article in Beatdom#22 this year about Jack Kerouac, To the Things We Can’t Remember. To the Things We Can’t Forget, where I said: “As a writer all I have is my past. As a person, I need to move on. Reflecting on life is healthy but only to a certain extent. There is analyzing and then there is over-analyzing. There is self-awareness and there is being self-conscious. There is learning from the past and then there is dwelling in the past. Lao Tzu warns: ‘If you are depressed you are living in the past.’

A writer always runs the risk of reliving the past ad-nausea; exacerbated by the fact that every writer knows that writing is actually re-writing, draft by draft.” So is writing purging? No, writing is bingeing.

The novel isn’t all down and out – we shouldn’t let people think that – there are some incredibly beautiful and moving moments – moments where you capture the living essence of the passionate, vibrant organism that is Chicago. You’ve written about the city before in 12 Chicago Cabbies. What is it that draws you back there?

I’ve gained material from every place I’ve lived, but my work about Chicago keeps getting picked up for publication. I think people are fascinated by Chicago because they are scared of it. Chicago has a certain gritty noir, a hard-boiled no-nonsense attitude. It’s a very working-class town. The harsh winters weed out the weak. It’s also where I spent my twenties, when I was more adventurous, so I have a wealth of material from that time.

In Chicago there is a community of creative people that help each other. At the end of Busking Blues all the characters come together to hear me play at the Gallery Cabaret. I realized that though I’m a loner I’m not really alone. Here were all these people who cared about an artist sticking his neck out and trying to do something real. Suddenly there was this great community feeling. It was really touching so I closed the book there.

John Guzlowski, author of Echoes of Tattered Tongues, described the prose in Busking Blues as an “honest and rocking and often intensely poetic language that evokes Kerouac and Bukowski at their best.” That’s damn flattering. Has the Beat Generation informed your own writing? I’m thinking in terms of style as much as content…

Yes, it has. It’s all about honesty. Like the blues, tell your truth and people will listen. It’s a sensibility that is important to rediscover right now. As far as style, yes the influence is there. All the art movements a generation before influenced the Beats: Surrealism, Dada, and film solidified into a true art form in the 1920’s. These were all things I studied in art school as well. Burroughs’ work draws from his own life but has a surreal bend. The cut-up technique is, basically, Dadaism with words. The Beats were the first generation of writers weaned on film. In Busking Blues, the prose is full of great imagery, flashbacks, juxtapositions, and the Burroughs montage technique he used in Naked Lunch. I do default to the tight prose and short sentences that Hemmingway, Bukowski, and Vonnegut advised. They proved that you don’t need big words to have big ideas. Yet, when the story calls for it, I will rant, run-on, employ montage, and spin purple prose with the muses.

As far as content, I’d say yes as well. The poetry world has always been accepting of autobiographical material. But when I read the prose of Hunter S. Thompson, the Beats, and proto Beats like Henry Miller and Celine… Eureka! You don’t have to hide behind some contrived fictional world to say what you want to say. You can be yourself. Just be honest. Real life is weird enough, and better than any formulaic genre fiction. Also, you can make the argument that reality is largely subjective and our memories are confabulation. It’s all fiction. Once you accept that fact, it frees you to write. Present the world as you see it. For the most part, I write about my own time. On occasion, I write fiction and period pieces – but my experiences are still there somewhere.

You’ve written numerous essays about the Beats, most notably for the literary journal Beatdom. How and when did you first become aware of those “angel-headed hipsters”?

Literally, the first day of college I found William S. Burroughs Naked Lunch like a dowsing rod on the library shelf. I just got out of jail. I didn’t see any other leather clad metal heads around school. So writers became my imaginary friends. One cold Chicago morning I was on the subway reading the part where the patients escape from Dr. Benway’s mental institution, and I just started laughing out loud. All the quiet commuters moved away from me. I knew at that moment, this was going to be my real education.

If we take On the Road, Howl and Naked Lunch as given, which do you feel are the three most important works by the Beat Generation?

Most important? Well, after the works you mentioned, Ferlinghetti’s Coney Island of the Mind, and Corso’s Bomb are the heir apparent. I actually think John Clellon Holmes’s Go captures the setting of late 1940’s New York best. It describes the actual synthesis of The Beat Generation, including Ginsberg’s Blake-like visions that sparked things. Personally, I think Burroughs final work The Western Lands is the most underappreciated work. He poetically combines all his edge zone theories and some physics into a narrative where he explores a hypothetical Land of the Dead through his dream state as a way to come to terms with his own impending mortality.

The Beats faced their share of attempted censorship, of course, with the trials of Howl and Naked Lunch. With the rise of so-called Cancel Culture, many writers and their works are once more under attack. What the fuck is going on out there?

The Beats fought and won the battle against censorship. The trials contesting Howl and Naked Lunch as obscene set the bar for what can be published in America.

Right now people are banning books again. Right now free speech is under attack by religious puritans on the right and the politically correct on the left. Be an individual and push back against both sides. Yes, there is a lot of disinformation on the internet – but we don’t need censorship as much as we need individuals who can think for themselves, who can recognize bullshit when they see it. It’s not that hard, because most things are bullshit.

You mentioned the Recession as being an underlying factor in Busking Blues, much like the Great Depression influenced, directly or indirectly, many great writers of the 1930s – specifically John Steinbeck and Jon Dos Passos. Is that fair comparison?

Busking Blues ain’t The Grapes of Wrath. I tried to keep the book buoyant. I am very upfront about how I brought a lot of my troubles on myself. The Recession wasn’t the Dust Bowl. But we were and still are Beat. In the book, booze and babes constantly tempt me, and one can try to blame it on some imaginary devil, but it’s really my own doing. In this sense, the book really isn’t promoting my own ego. It’s self-deprecating. The real main character isn’t myself but Chicago, and the real life people who I interviewed on the street and wrote songs about. It’s about the side-effects of Capitalism. It’s about what an uncompromising artist is willing to do for a buck. I have tried to live simply where I can make my art without the clutter of materialism. Turns out you spend even more time worrying about fucking money. I always knew my music wasn’t for everybody, but I think there is something in this book for everyone.

Where are you going from here?

I’m really looking forward to the small book tour I have lined up with stops in Trinidad, Colorado – Belle, Missouri – Michigan City – and ultimately back in Chicago. The guitar is coming with me. I mean, it has to, I’ve had too many requests; and it fits the busking theme to do multimedia readings for the book. I have readings at Phyllis’s Musical Inn and The Gallery Cabaret, two rooms where the book actually took place. Also, a feature with Fernando Jones, a character in the book, at a Southside jam at the jazz and blues venue Knotty Luxe. It will be like a homecoming. Maybe I won’t come back.

Busking Blues: Recollections of a Chicago Street Musician & Squatter is available now on Amazon or at https://www.magicaljeep.com/product/busking/98

Photographs by kind permission ©Alexis Rhone Fancher.

About the Interviewer

Leon Horton is a countercultural writer, interviewer and editor. Published by Beatdom Books, International Times and Beat Scene magazine, his numerous essays and interviews include ‘Hunter S. Thompson: Fear and Loathing in Utero’; ‘Charles Bukowski: Only Tough Guys Shit Themselves in Public’; ‘Where Marble Stood and Fell: Gregory Corso in Greece’ and ‘Gerald Nicosia: In Praise of Jack Kerouac in the Bleak Inhuman Loneliness.’