Five Broken Cameras is a remarkable new film about the conflict in the Middle-East. There have been many documentaries on this subject, but this one is being touted as something special. After the showing in Riverside Studios as part of the Doc House Festival www.dochouse.org there was an immediate standing ovation from the audience as the joint directors took to the stage to answer questions.

The directors are Guy Davidi and Emad Burnat (see below) and their collaboration is a complex one. Guy is Israeli and Emad is Palestinian, but they themselves play down the significance of this. It is not a selling-point. This was cleverly explained by Davidi who also said they included footage of Israeli-Palestinian co-operation in the resistance movement but did not wish to make it a central theme. Both men met in activist circles, are friends, and their collaboration feels ‘natural’.

The film, however, is really Emad Burnat’s. This amazing documentary works so well because it is personal-political. It is his footage and his voiceover; and it is his life. He tells how he originally got the first of the ‘five broken cameras’ to celebrate the birth of his son Gibreel and to make home-movies. As this was happening, the Israelis began sending bulldozers into his hometown of Bil’in. Their plan was to steal land from the Palestinians, build new housing for new settlers, and erect a protective barrier between those settlers and the residents of Bil’in. One moment we enjoy the vista of a new-born son, the next moment we see JCBs – sold by Britain – digging up olive trees and moving them out of the way. It really is more informative than a thousand newspaper articles, but it is also moving.

Emad is one of the leaders of a group of activists who decide to oppose the Israeli plans even as they are being ruthlessly carried out. Their tactic is to demonstrate weekly, every Friday evening, after prayer. Emad brings his camera and films the colourful protests, the chants and banners, and the passionate confrontations between the activists and the IDF soldiers. Two important characters emerge in Emad’s spoken word narrative, his friends Phil and Ameed. Both are large men. Phil is the eternal optimist who is loved by the town’s children because he seems to radiate a hope that is scarce among the adult population. Ameed is a mustachioed drama queen who is ‘always making a scene’ but this makes him an excellent demonstrater. Again and again we see him histrionically making loud speeches to astonished Israeli troops. ‘Where is your heart?’ he roars. Another time he falls on the ground as if he’s been shot and begs the Israelis to kill him. It is hilarious to watch his antics, except when the Israelis decide they’ve had enough and cart him off to prison. Regularly, Emad’s friends and family are arrested, for nothing more than shouting.

One decibel too loud and you vanish… for months or years.

One of the fantastic features of the film is Emad’s monologue. Amazingly, it was written by Guy Davidi who was able to capture his friend’s way of speaking but add the necessary literary structure and poetic refrains needed to tell the story. Viewers, of course, read the English subtitles but are still able to hear Emad’s voice, his gravelly Arabic, which burns with a dignified fury throughout. The sound of his voice is one of the key features of the film’s greatness, adding a visceral dimension, even though we don’t understand what he is saying. It is the voice of the oppressed; its tones are sad and wise.

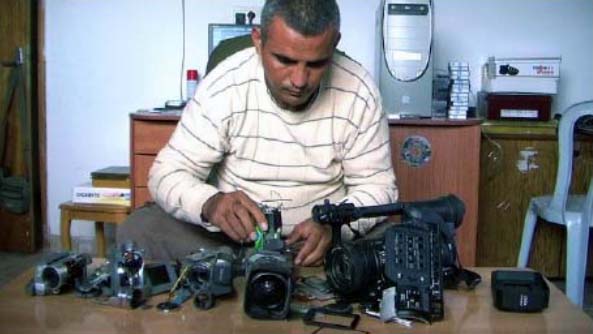

The main structuring device is that of the titular ‘broken cameras’. Filming the protests is very important in Palestine because of the very real threat of injustice. The protestors are unarmed. The Israelis are armed to the teeth. Cameras are a warning to the soldiery that their actions are being recorded. And they really don’t like it. Trained snipers aim at cameras and are thankfully successful i.e they mostly get the cameras rather than the cameramen. One by one, from 2005 to 2010, Emad’s cameras are shot at or vandalised. This has its own interest. Though it is not only a film-makers’ film, it is a film that would interest film-makers even if they weren’t interested in the Middle-East conflict.

It is not only the Israelis who object to Emad’s all-seeing eye. Another leading character in the narrative is Emad’s wife Soraya. She implores her husband to stop filming because of the double risk of imprisonment and/or assassination. These scenes are both moving and comic, because the cinema-goer already knows that he will not take her advice. Emad himself tells the viewers how he feels as if the camera gives him protection, but actually it’s something of a miracle that he’s lived to tell the tale. We learn what a film-maker really is, someone compelled to film. A great moment is when he has the idea of showing some of the footage to the people of Bil’in. It has the effect of lifting the morale of the activists, and it is out of these necessary, tribal, private screenings that the internationallly released film has come. Altogether he shot 700 hours of footage. The decision to tell the story of Emad’s own life meant that it was relatively easy to sift through the 700 hours and find what was needed.

I do not wish to spoil the film by telling too much of the story, but it really is something of an epic. There is so much going on. So many stories. So much of the drama that conflict is rich in… One moment I will mention as outstanding is the footage of one of Emad’s brothers being arrested, and how his parents both argue with the soldiers and beg for his release. It is incredible to see the weeping mother charging at armed men and to see Emad’s elderly father climbing onto the jeep in which his son is captive, clinging to the roof, and demanding the release of the prisoner.

As one watches the events unfold, it impossible not to be outraged by how the Israelis behave. It is striking to see how racially similar both peoples are and the very different realities they inhabit. Their shared reality is fratricidal. Emad calls himself ‘a peasant’. He lives off the land. The connectedness of the Palestinians to their land makes the Israeli incursions seem like violations of the sacred. The Israelis are so heavily equipped it beggars belief. They seem like very small boys with very big toys. They also seem like the U.S. Army. They are very young men and women. During one tense moment of resistance, we see a young soldier talking into a headset to an absentee overmaster. ‘What do you want us to do?’ he shouts nervously, awaiting the next command. They deal with most protests by throwing tear-gas grenades, and shooting their rifles to miss. Except they don’t always miss.

It is depressing and uplifting by turns. Another of its points of interest is that it’s a marvellous film about activism and activists. It dignifies political protest, and validates direct action. The people of Bil’in are an inspiration. Emad feels his filming is like healing and that: ‘By healing, we can resist oppression’.

It was a pleasure and privilege to attand a screening with the film-makers present. ‘Is it heroic?’ Ken Campbell always asked. This is. Asked by a member of the audience what he would like the audience to take away with them, Emad said that he would like people to remember that this is not a film, but real life.

Niall McDevitt