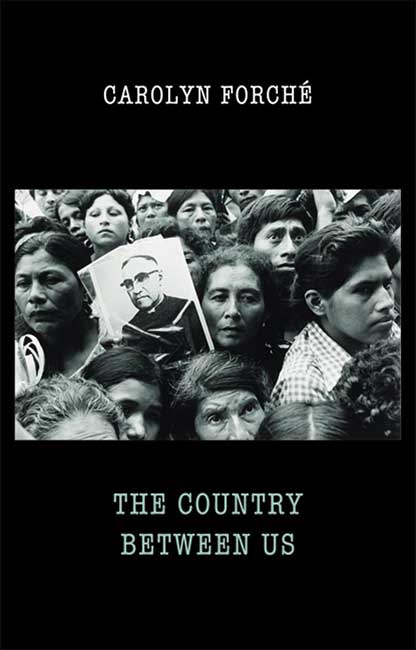

The Country Between Us, Carolyn Forché (Bloodaxe)

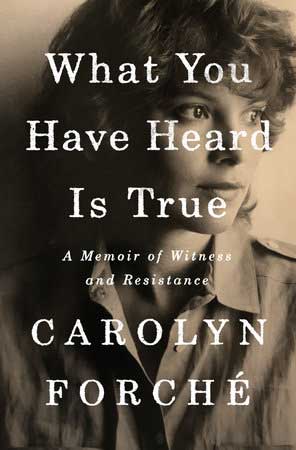

What You Have Heard is True, Carolyn Forché (Allen Lane)

Thirty years from now, you might

hold this room in your hands.

–‘Photograph of My Room’

Almost forty years from the first publication of Carolyn Forché’s The Country Between Us, Bloodaxe have reissued her seminal book of poems which documents the author’s trip[s] to El Salvador (and elsewhere), and her return to an everyday life which will never be the same again. Meanwhile, Penguin have published What You Have Heard is True, ‘a memoir of witness and resistance’ which takes its title from a key poem in the poetry book and documents Forché’s travels to El Salvador and her relationship with the country as the result of that first tip.

Forché has edited a pair of anthologies of poetry that bear witness to human history, as well as further volumes of poetry (also published by Bloodaxe) but I confess that neither The Angel of History and Blue Hour have the power that The Country Between Us has and are no longer on my shelves. This power derives from a sense of innocence abroad, a first encounter with corruption, warmongering and atrocity, in stark contrast to the American sensibility Forché seems to initially carry with her. Soon, she realises that ‘There is nothing one man will not do to another’ (‘The Visitor’), perhaps as a result of visiting ‘The Colonel’ who is happy to pour a sack of shrivelled human ears onto the floor and announce that he is ‘tired of fooling around’, and ‘As for the rights of anyone, tell your people they can go fuck themselves.’

This is in stark contrast to the whiff of hippy traveller innocence that Forché’s poems also contain, and works because the story is told, in fact recounted, in unemotional prose. Only the reader judges, the poem’s narrator does not, she simply reports what she has seen. This is the poetry’s strength, because it avoids polemic or any insistence on telling reader how to respond. The reader is shown what happened, occasionally asked questions, and left to make up their own mind.

The beginning of ‘The Colonel’ provides the title for Forché’s memoir which is told through a mixture of narrative, passages ‘written in pencil’ (which suggests they are notes from the time), quotations and photos. It reads as an expanded version of the poetry and is, to my surprise, just as powerful and detached. It’s clear that the poetry was distilled down from a much wider engagement with El Salvador than the concise and focussed poems suggest, and of course this memoir is told many years later, and over a long period of time, though Forché is at pains to point out she used ‘research to confirm the facts’ rather than just memory.

The story begins with a dismembered body in a sorghum field, then backtracks to a knock on the student poet’s door and the arrival of Leonel Gómez Vides, who persuades her to travel to El Salvador to write about what is happening and the war he believes will soon happen. Vides is a brave, self-possessed man who moves between territories, classes and enemy zones with apparent ease, though it gradually emerges just how careful and wily he is.

Forché is initially lost in South America. ‘I should go home, I thought’ she writes, as blood, bodies, dust and confusion surround her. Looking back she tells us that ‘Later I would understand that here the dead and the living were together’. And sometimes they blurred:

There were eight attempts to assassinate Leonel, and finally the military sent a unit of sixty soldiers to apprehend him. He received an advance warning and managed to hide himself in a large pile of garbage against a building on his street. He had to stay in the garbage for hours. ‘The dogs knew I was there,’ he said, ‘the children knew I was there, everyone knew I was there except the army. I was very moved that no one gave me away.’

Vides is finally given political asylum in the USA, where he keeps on campaigning for human rights and keeps information about the war and abuse in El Salvador flowing to senators, congressmen and the public. Forché and Vides returned to the country when peace returned, and Forché also made one final trip, following his death, to sprinkle his ashes in 2009, which is there this memoir ends. Or almost. The whole book is not only about the poet and her story but about her relationship to Vides and how he enabled her to write. The book ends with her answer to those who ask what it was like to work with him and who he really was:

It was as if he had stood me squarely before the world, removed the blindfold, and ordered me to open my eyes.

Rupert Loydell