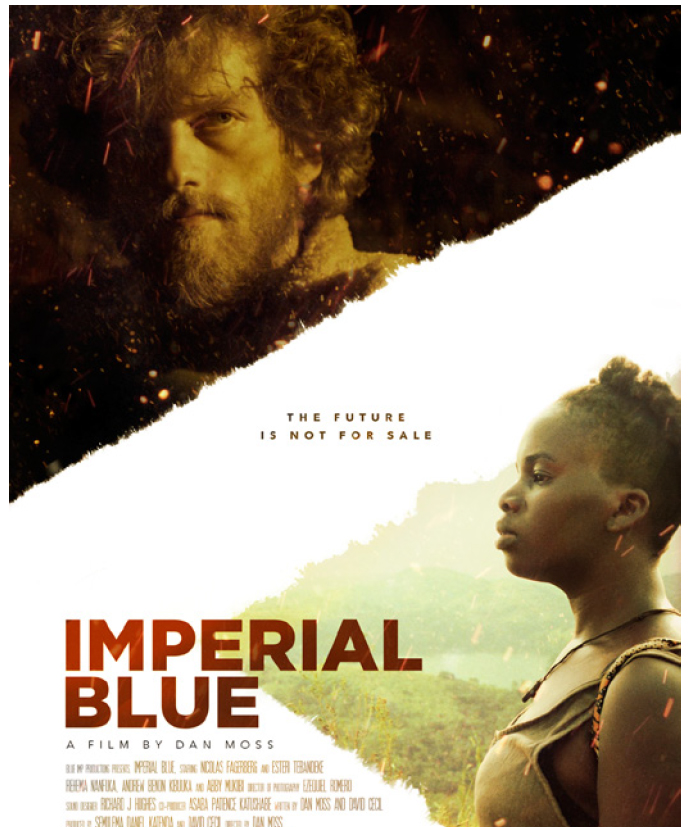

Reviewing IMPERIAL BLUE – A film by Dan Moss (Blue Imp Films 2019)

The notion of the quest lays at the heart of not only all human stories, but all animal ones also. Whether it is for food, warmth, closure, security or treasure, the unresting spirit as both a narrative imperative and source of elucidation and entertainment underpins and explains what connects us to a previously uncharted chain of events, whether in the form of the artful documentaries of Werner Herzog, the shocking factoramas of John Pilger and Errol Morris, or Ingmar Bergman’s ancient Knight courting death on the loneliest ridge. Dan Morris and David Cecil’s new film IMPERIAL BLUE is a fascinating mix of documentary style realism and drug fuelled fantasia set in the furthermost reaches of Uganda, where both encroaching forest and stolen land house the possibilities of future discovery and salvation while at the same time housing danger of the most murderous kind.

In the film, what IMDb describes as a ‘roguish drug dealer,’ Hugo Winter, played by Nicolas Fagerberg with a slightly heavy handed form of angst travels to the African continent in search of a semi-mystical drug Bulu, the ingestion of which bestows on the taker the ability to see the future. At a time of political, moral and social crisis this lends the concept written by Moss and Cecil a faintly Utopian air, with the foreboding forests and back streets of the broken African towns acting as breeding grounds for a new form of hope, and indeed this is a notion that might have been achieved with a different style or choice of protagonist; one more attuned to the wonders or potential for wonder than the chosen character of Hugo Winter, whose ever present anger and jadedness afford the story a more nightmarish quality. Its arguable if a different sensibility or set of decisions would have altered the film but as Dan Moss stated in a post screening Q&A at the Raindance Festival, his and Cecil’s love of noir led them into this specific style and territory. What results is reminiscent of both Coppola’s A.N. REDUX (particularly the long excised French Plantation sequence), Claire Denis’ WHITE MATERIAL and the John Huston of UNDER THE VOLCANO; a heat soaked voyage into both silence and recrimination and a gathering miasma of threat. This is all to do with specific story choices of course, but taken as it is, the film becomes a new form of Kurtzian/Conradian travail through and into the heart of a far reaching and often bewildering darkness.

Despite the fact that the story centres around Winter and his relations with the two Ugandan sisters Kisakye Gloria and Angela Mbira, played by and Esther Tebandeke and Rehema Nanfuka, who respectively act as both guardian and temptation, much of the power of the film rests in the structure that Moss and Cecil have contrived and in Moss’s assured direction and Ezequiel Romero’s audacious cinematography. Each shot is beautifully measured and composed and has what very few modern films possess, or see as useful in terms of possession: a form of gravitas. One feels not the filmmaker’s outside eye observing events, but rather fate’s own viewpoint, or, perhaps, the detached and coruscating, if achingly, withheld judgement of an unappeased jungle spirit or God. Winter’s search for Bulu is fired by the settling of debts to a London Ganglord, but the notion that the drug once obtained could bring financial gain is outbalanced by the potency for change that it offers. Winter ingests the cocaine like sediment of the blue flower several times in the film, ultimately sacrificing himself to it when he sees that his own personal options are running out, and one feels a degree of both frustration and enchantment at this lost or truncated opportunity. Like the black roses that bloom through the Scottish highlands at the end of Troy Kennedy Martin’s seminal BBC TV series EDGE OF DARKNESS, these blue roots offer the last vestige of hope in a word all too ready to succumb to damnation. That they and the secrets of their preparation are protected by Tebandeke’s sacred Kisakye is even more telling. She has the resonance of an ancient myth, whether African, Norse or Greek; the caretaker or protector of that last resource intended more for the planet itself than for its inhabitants.

Winter certainly does nothing with his visions other than illuminate his current predicament. In one sequence he defies the revelatory aspect of the plant itself and Uganda’s resident gods by outwitting the housing village’s resources and saving a drowning boy from the river, so the notion of Bulu’s usefulness for man is thereby brought into question. What becomes more appealing is the idea that it is in fact solely for the land itself, which has already been fought over and stolen from Kisakye and Angela’s father, a factor that incurs one sister’s enlivened spirituality while hastening the other’s descent into decadence, damnation and death. The land in defying the transgressions of man has evolved at a faster and higher rate, growing the seeds of its own salvation as it is worn away, worried and drained by man’s petulant wasp, or be, eternally mining it for salves to the sours we make.

Extended sequences in the film play in near darkness. This is visually challenging, emotionally arresting, and technically accomplished. We see outlines of faces, shredded by the intense night, or crescents of expression, as in the once hidden dimensions of a swollen Brando, before plumes of fire and distant beacons offer some sense of proportion and place. This visual assurance helps to lift the film from its basis as mere documentary of discovery and lends the quest a more magical air. It was Burroughs and Ginsberg’s search and detailing of the hunt for Yage in the late 1950’s that sprang to my mind as I watched the film, along with Conrad Rook’s near forgotten CHAPPAQUA, in which an addiction ridden American princeling attains a soul settling sense of nirvana while undergoing cold turkey in a French institution, through the dream tinged memories of discovery across distant plains located somewhere in a far east of the mind.

Moss and Cecil in both script and film keep things carefully balanced. Extended darkness gives way to spectacular scenery. Angst and suffering enable fleeting moments of joy and satisfaction, before the blue taints on Fagerberg’s matted beard remind us that while drugs provide escape, the true destination to which they deliver us is simply an inch deeper down in our pain.

As a truly independent film attempting to make its way in the world and skilfully fusing elements of noir, cinema verite and science fiction IMPERIAL BLUE is something of an accomplishment. At a time when film plays endlessly with the stereotypes of accepted action, its locale and emphasis are refreshing. While there are plenty of frightening and threatening figures of all denominations, there is also the simple tactility of a woman and child and of a world longing for its own repair. The hazey, phased hallucinatory sequences, artfully achieved by Romero’s detaching of the lens are ingenious and denude the need for the CGI that stains most modern film now like dye through cake, adding to its effect, affect and authenticity. The two women are particularly effective and the near constant soundtrack by David Bryceland does not fall into the trap of what Hollywood music does by telling you what to feel; instead it and the numerous other pieces of source music reflect and enhance the environment, providing some of the detail that in the night sequences we are kept away from.

IMPERIAL BLUE is a trip Philip K. Dick might have taken, if he could have prised himself away from the catfood and the pink triangle of light. It is the kind of Science Fiction that JG Ballard celebrated; the glimmerings of a future that remain mired in the present. It is only when we adjust our perceptions that we will be able to see each individual light some other higher source has set for us. Once recognised we will be able to distinguish what it means to be truly shining. Here, in this deep blanket of darkness, stained as it is by blood, sweat and effort, something old feeds the new and just as its borrowed, it allows for transference and for deeper truths in the blue.

To seek should be all. Here, then is seeking.

The Quest is continued.

And as we ascend, so we fall.

David Erdos September 22nd 2019

https://drive.google.com/folderview?id=1FD0BMeh-QQzYgi1Pqxl0DaLHferT3fOT