from THE RUMMAGING DIARY OF A GENTLEMAN-POET

Saturday, August 2nd

I have had a letter – on paper, in an envelope, with a stamp on it: a surprise in itself, in this age of instant massaging, twitching, and Artificial Idiocy – from 27 (I counted them: 27!) “admirers” of my work, saying that they miss reading the regular instalments of my Diary, and that I must recommence it immediately before they all lose their minds. I am not at all sure that I “must” anything, other than certain unavoidable bodily functions. Much as I enjoy the occasional compliment from a fan, these people really should understand that genius comes at a price. Why do not they go back and re-read the earlier instalments published in this popular journal? Everything I write is worth reading at least twice, if not more! Also, if they would care to send me a small financial consideration, I may consider starting things up again on a regular basis. In the absence of financial inducements, they will have to put up with only occasional treats – like this one.

Saturday, August 9th

I have been rummaging among old files and papers while I try to find things to put into my “Collected Poems”, although the publisher who suggested doing the book seems to have gone a little bit quiet and has of late begun to take an inordinate amount of time to reply to emails, and his telephone is constantly engaged. And when he does write to me I am sensing a distinct lessening of his enthusiasm for the project. Given that it was his idea I am a little concerned, but perhaps he is distracted. From what I know of his private life I would not be surprised. She is much too young for him.

As I was saying, I have been rummaging, and in a box labelled “Rejections” – a box which, incidentally, has very little in it – I came across a piece of prose that I do not remember writing, and I think it’s not at all bad. I have never written much in the way of prose, although I would be good at it if I could be bothered. Of the piece in question, after perusing, I deemed it worthwhile to make one or two little adjustments, and since I have typed it up I will include it here. I think it is alright, as far as it goes. It labours under the title of “My Childhood”, a title which I will probably, nay, must change, because it wasn’t.

My Childhood

I had only been at the orphanage for a couple of years when one day a lady nurse, a lady I now recall as having had tremendous legs (which surely I must have been much too young to appreciate) took me by the hand and led me along a long corridor until we came to a door. She opened the door and took me into a room where there was a big bed. She led me across to the window and opened it, then she picked me up and sat me on the sill and swung my legs outside so they were dangling. Then she told me to jump, at the same time as giving me a gentle shove. I landed on some yellow flowers that were about six inches below my feet. (I should have mentioned that we were on the ground floor.) A voice behind me told me to run, so I ran. I ran along the tree-lined drive, past the gatekeeper’s lodge where the gatekeeper’s wife was hanging out the washing, past a black and white dog, and out on to the main road, but I didn’t know which way to turn so I tossed a coin in my head and it came up ‘tails’ so I turned right and ran past the Post Office, past the entrance to the park where some men were felling trees, past “The Haunted House”, which is where ghosts lived, past the Church where we were dragged every Sunday to sing to the God, past the bridge over the canal and its barges taking coal and steel to factories where they made smoke, past the allotments, which is where old men were in sheds, past a field where gypsies were encamped and where it was said if children went in they never came out again (I speeded up), past a bus that was broken down, with all its passengers milling around at the side of the road hurling insults at the driver, past the new housing estate that was being built, past a very big house, which I now know was a sanitorium, which was on fire, and people were running out of it screaming, although some were laughing, past a big hole in the ground that had voices coming out of it but I did not stop to hear what they were saying, past a statue of The Duke of Wellington I think it was, although it might be someone else along the same lines, they all look the same to me, past a pedlar selling trinkets from a tray, past a waterfall beneath whose cascade frolicked lithesome maidens in swimwear and nice hats who called to me but I was too young and innocent to understand what they meant, past the reservoir which was empty, past the railway line and the level-crossing where in 1978 a famous poet would end it all by stepping in front of a train (I think he wrote a poem about it), past a signpost that said “To The Sea” and after a few yards I turned back and I took that turning and ran towards the sea, the sea I had read about and seen pictures of in books and in my head, at night I had sailed that sea in ships, through becalmed and be-stormed, and I ran past children who would never grow up, past old men and women sat at the roadside selling seagulls, some dead and some alive, past a man building a great big boat, a boat bigger than any other boat he had ever built according to I suppose it was his wife who was telling everyone about it using a megaphone, the boat was certainly very big, and I ran past a row of shops, all of which sold things made of seashells, covers for books made of shells, little men and women made of shells, ashtray shells etc., and I ran past a hotel, past an ice cream parlour, past a stall selling fish and chips, past a widow stood gazing helplessly out to sea from where her sailor husband would never return, and I ran past the sea itself, I ran and I ran, I ran with my legs pumping and my heart pounding past the sea, and I kept going and going and going, and I didn’t stop, not ever.

*

As I said, I do not remember writing that, and I think it’s not too bad, but I’ll probably not do anything with it. I do not really know what it is, apart from one more indication that a genius’s discarded pieces are better than almost everything else out there in literature land. But it is not a poem, and I disdain the so-called prose poem, which is more often than not written because the so-called poet has not the discipline required, the attention needed, to command the movement of conversational free verse. Stapled to the version I found in the box is a note from the editor of a journal I shall not name. It says “Don’t give up the day job.” Where is he now, I wonder?

.

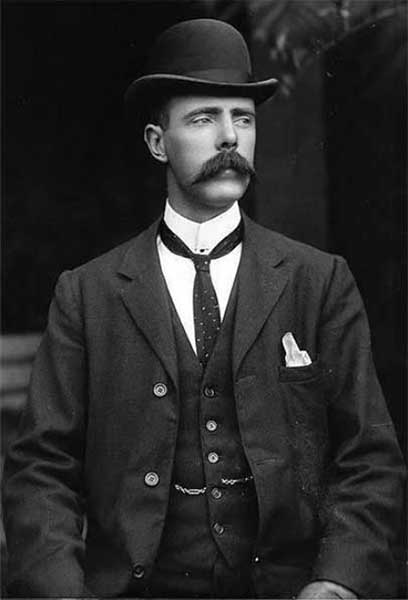

James Henderson

.