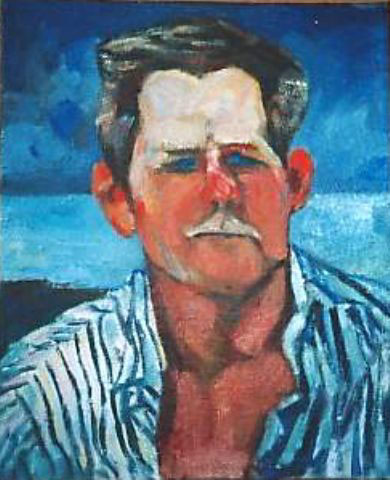

Self Portrait Stanislaw Frenkiel – 1978

CHAPTER ONE

11th November 2003

7am

This art business

The cab door opens. A contraption appears like a flattened tripod, tapping at the ground. Then a battered shoe, grey corduroy leg, and the whole of Josef Stefko. steps into the bitter breeze coming off the Thames. Bundled in a black coat he wraps the red woollen scarf around his neck and ears, his thick hedge of white hair making a hat unnecessary.

‘Bit early for Tat Modern?’ says the cabby.

‘Old tat, and so it is,’ says Stefko, deliberately thickening his accent, ‘especially mine.’

‘You famous, then?’

‘Nie,’ he says, handing over a twenty-pound note. ‘And please do keep the change.’

As the cabby drives off, Stefko and his peculiar walking stick make their way down the long concrete slope towards the entrance declaring –

JOSEF STEFKO – A RETROSPECTIVE.

A side door opens and he steps into the rarefied atmosphere of Tate Modern.

‘Dzien dobry, Mr Stefko,’ says the security guard. The door closes again, sealing off the outside world. ‘Good morning to you yunk man’’ he says, ‘and learn English if you want to get on, you bloody Pole.’ The bloody Pole, grinning, gives a middle finger salute. ‘You need to search me for bombs, no?’ says Stefko, holding out his arms, cruciform, the walking stick hanging from his wrist.

‘No,’ says the guard, ‘and good luck for tonight.’

‘Thank you.’

Stefko continues, down through the Boiler Room, past the shop with his own works miniaturised on bags and T-shirts looking back at him. Then into the Turbine Hall once containing the beating heart of the great power station. There is a massive virtual sun, not yet switched on. He like’s the Dane’s work: well-intentioned, plenty of heart. And heat.

Turning left, another glass door opens and Stefko walks into an place that reminds him of a hospital reception, with its cloakrooms, lifts and escalators. He smiles, thinking about all those paintings and sculptures waiting in wards for their visitors.

His bladder hurts and he heads for the toilet.

Unzipping, he thinks of how well his little doll has served him over the years. But the energies coursing through him now are mental, spiritual. As he waits for his pee to come he looks down at his derelict brogues. Bought in Oxford fifty years ago, when he’d been the keynote speaker at a conference The Importance of the Émigré Artist. His body had absorbed their stability, up, through his legs, into his heart and brain, rooting him finally in this country where he’d nourished a pallid English art scene with new form and colour.

After a small amount of urine, he zips up, walks over to the washbasins and washes his hands. He looks in the mirror: his blue eyes still lively under the wire-rimmed spectacles, like creatures in a rock pool. His jowls drag only slightly at his mouth, and he can still manage that charming smile, the hearing aid a discreet beige button behind his left ear. He’d preferred his hair and stubby moustache grey, but the white comes eventually, like the snow on the Tatra Mountains.

Jan Woolf

.