View from the back of Frizington Main Street, 25th October 2020.

A visit to the wild, ex-industrial coastal strip of Cumbria is always bracing . . . which has the observational texture of an outsider’s or tourist’s comment. While it’s true that this area was not bred in our family’s bone, since circumstances shifted us further west after a decade in the remote landscapes of the Northumberland and Westmorland fells, most of us have come to know it well.

Frizington centre

From the gardens and conservatories on slopes above Windermere to the kitchen sinks of Workington or Barrow[i], Cumbria’s rich/poor divide is acute. One of my sons has for some years lived in Millom, where the partially landscaped ‘slaggy’ left by extensive ironworks now otherwise vanished, rises at the end of the street. Millom lies on the western shore of the Duddon estuary, excluded, along with Haverigg prison, from the Lake District National Park. Travelling north under the 2000-foot brooding fell of Black Combe, from Silecroft to beyond Ravenglass, the Park is unnoticeably regained and being now part of a UNESCO World Heritage Site, shouldn’t the land here at least be protected?[ii].

Sunburst, Frizington.

Blighted by the nuclear mess of Drigg and Sellafield (formerly Windscale – a whitewash which fooled no-one) as well as the criminally retrogressive plan to reopen Woodhouse Colliery, Whitehaven[iii] (inevitably supported by some in a community desperately short of jobs), much of the Cumbrian coast has long been treated with contempt. Before moving further up the coast, our eldest son lived at Calder Bridge, less than two miles from the nuclear reprocessing plant, and received one day a leaflet detailing the siren codes for varying degrees of danger from radiation leaks or fire. Advice ranged from SHUT YOUR WINDOWS AND STAY INDOORS, to – basically – GET THE HELL OUT!

Main Street, Frizington, looking towards Lank Rigg and Crag Fell

Turning north-east at Egremont, the road climbs gradually, the wasteland atmosphere resisting any obvious beauty or focus. This is no West Penwith or Elmet[iv]. Towns and villages such as Cleator Moor and Frizington, where our eldest son subsists, evoke the Wild West under a maritime climate. Their original terraced houses may be too squat and solidly built to become as wind-worried as the creaking wooden wrecks or shanties of gold rush towns lost on desert plains or abandoned in the Rockies, but the sense of frontier remains, even of hideout and tolerant anarchy. They cannot become ghost towns, since few of the inhabitants have anywhere else to go.

Frizington Pre-school

Yet despite the poverty inherent in these settlements, particularly under ice and rain, the sense of community, in a generalized, undemanding way, is strong, and most people you meet – pensioners, middle-aged and young – are cheerful and friendly, despite that for many it must be the end of the line.

According to an estate agent’s board, the reasonable shell of local saloon, The Griffin, has recently been sold. Perhaps, before long, the doors will swing open again and the tinkle of a piano be heard in the street? Meanwhile, the Whitestar Football Club[v] appears to be the social hub.

Occasionally, sheriff or deputy crawl or turbo-charge the main street under blue flashing lights – rarely to engage with the inhabitants in person, always missing the high-powered or unsilenced exhausts of other private cars occasionally punctuating the night in explosive, accelerative bursts.

Has covid knocked back the heavy traffic to some degree? Certainly, the crash and grind of the oversized lorries which pass my son’s front door seem to have lessened since last February. Double decker buses though still faithfully run, no matter how empty.

“40 lbs. of lead piping and a dozen chromium-plate mixer taps on Chiseller in the 3.45 at Aintree, ta.”

Thanks to blankets around his living room, this space at least can be slightly heated, or, on alternate days, the front bedroom. Connecting areas echo outdoor temperatures, while the bathroom, downstairs, out on a limb, is arctic. Here you needn’t move your arm to brush your teeth, you merely put the brush in your mouth and let shivering do the work. Which flippantly brings to mind Captain Oates and his famous phrase[vi] – not that it fits, no pre-meditated sacrifice being here involved.

Gas and electricity suppliers are not so community minded, their metered connections in rented housing always being via extortionate tariffs, bound to keep the poorest poor. We’ve offered my son a dehumidifier for Christmas, but he doubts he could afford to run it. Baths don’t come cheap at the ice cap, so are limited, like hot water, to every other day at most. His situation is only one of thousands in the area, families and the old. Jobs are scarce and before the covid crises the unemployed were continuously hounded to search for work that doesn’t exist. My son was heavily penalized for missing a job appointment when his bicycle broke down.

Bungalows, Frizington, Main Street, October 2020.

As usual, we ended up talking half the night, feeling that after the clocks went back at 2am, we’d fortunately been granted an extra hour out of thin air. At about 3, the last thing he said to me before I shut my bedroom door was: “Watch out for the ghost!” indicating where an old friend of his who’d visited a few weeks earlier had seen the grey spectral form, standing at the end of the bed. “What had you been smoking?” I joked. “Nothing,” he laughed in reply.

I wondered if the thought of this departed prospector, miner, cattle drover or gunslinger had made the room go suddenly very cold, but realised of course, that it was always this temperature when the weather took a turn for the worse.

* * * * * *

Next morning after a burst of violent hail there was some sun in the sky. Dressing quickly, I went outside for a walk to get warm. A tractor passed the funeral director’s opposite and down at The Griffin roundabout a woman rode through on a horse. A few cyclists also spun past, one braving old-style shorts – no fair-weather wimps survive long around here! Even a lone deputy came kerb-crawling by, briefly, behind glass, waving a greeting to a wobbly pedestrian with sticks – who tried to raise one to the sky.

Towards Weddicar Rigg

Some of the names hereabouts drill into the mind: Wath Brow, Lingla Bank and Foumart Hill; Bleak House, Acrewalls, Routon Bridge . . . Weddicar Rigg embraces the sun while Winder Gill has disappeared in hail. A siren bleats loudly, firing up the road towards Rowrah. The river from under Starling Dodd (633m) via Ennerdale Water, sounds like a clearing of the throat: “Ehen.”

Abandoned Council Chambers, Frizington, October 2020.

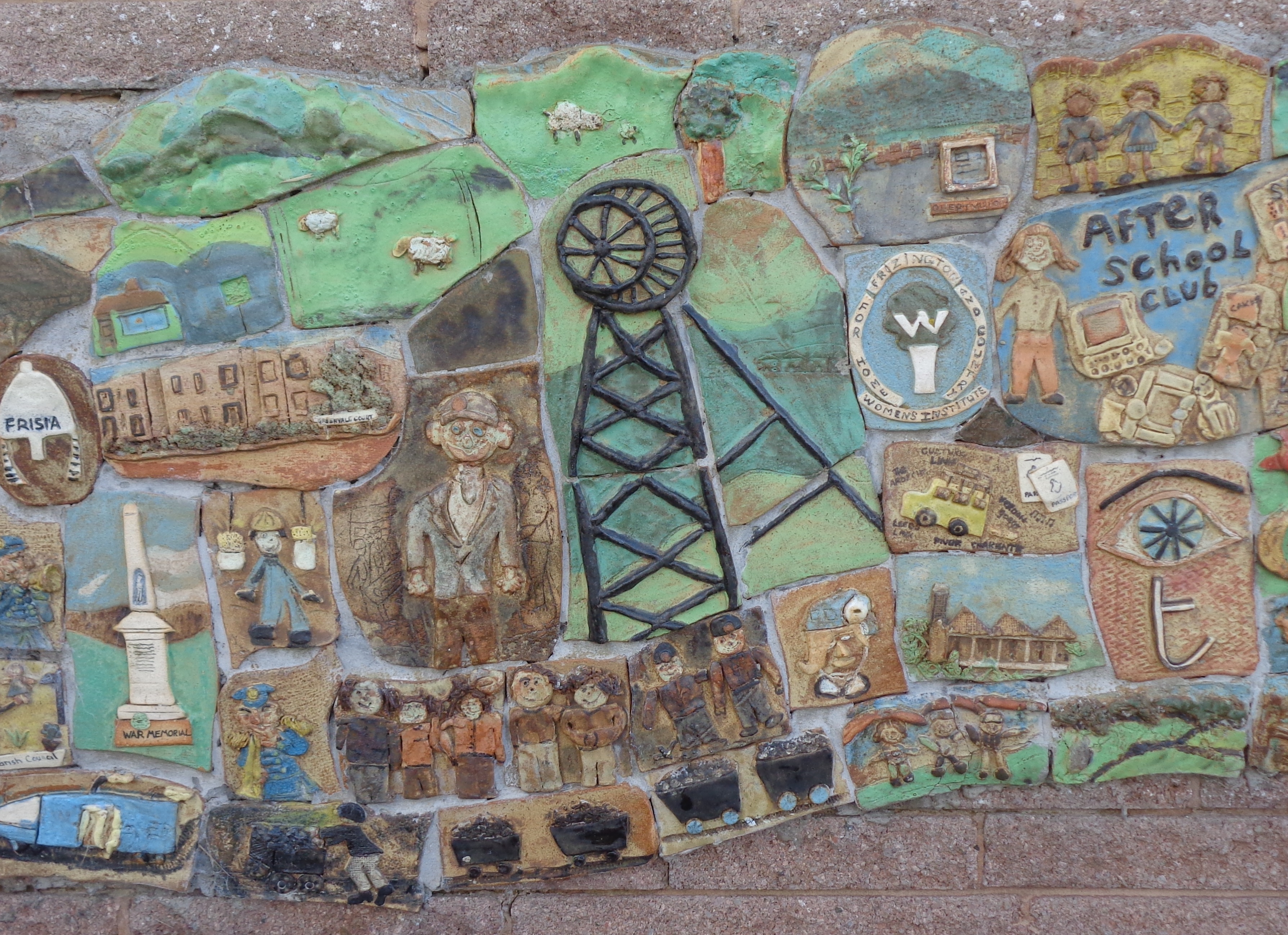

Yet this village has its own contrasts, areas or houses that rise above the general fortune. The red sandstone blocks of the council chambers may be colonized by lines of grass and the windows smashed but the school looks cheerful and there’s a wonderful, ceramic mural depicting the village and its history.

Frizington, Main Street, October 2020.

A blaze of low sun illuminates the fire station and the moorland fields behind. This village exists on a border where the traces of mineral railways crisscross the land and disused quarries abound: one of the last former coal and iron ore mining settlements before the National Park begins. At Cleator Moor, this boundary is less than half a mile to the east.

Meanwhile, as the mountains around Ennerdale’s lake emerged from the storm, I remembered other villages just a few miles further inland whose newly built villas include modernistic touches such as acres of glass. The gap between the avoided and the desirable is not wide, and the decorations for Halloween universal.

By the way, I never did meet that ghost. Perhaps, if it’s true that ghosts are creatures of habit, it had been confused by the twice annual farce of the clocks going back or forward from one fake time to another?

© Lawrence Freiesleben,

Cumbria, October 2020

NOTES

[i] http://internationaltimes.it/an-existential-road-trip-to-barrow-in-heavy-rain-notes-from-a-park-shelter/

[ii] https://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2018/sep/13/ban-4×4-off-roading-in-the-lake-district-campaigners-say – a controversy that still rages

[iii] https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2020/jan/15/new-cumbria-coalmine-incompatible-with-climate-crisis-goals

[iv] https://www.cornwall-aonb.gov.uk/westpenwith https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Remains_of_Elmet

[v] Very close to my son’s house, I assumed this was for local football players to go in the evenings, so was surprised to see members, some in full football kit, out on the fire escape, chain smoking. Correcting my impression, my son told me it was a social club where members gathered to drink and watch live football on a large screen TV. However, some weeks later, he saw a group in football kit, burst from the building and head enthusiastically to a nearby field dribbling a ball. Now, he is confused. Was my initial assumption half correct? Did the TV break down? Or did they just suddenly have a desperate urge to play football themselves?

[vi] “I am just going outside; I may be some time.”