I could start with a nod to Franz Kafka’s Metamorphosis by writing:

“Rupert Russell awoke one morning from unsettling dreams to find the world had gone mad.”

But that isn’t quite right and doesn’t fully describe the situation that filmmaker Russell found himself when he awoke on the morning of November 9th, 2016, to the news that Donald Trump had been elected the 45th President of the United States of America. Russell described it better himself:

“I felt a sense of unreality. That I had woken up on a different planet than the one I had gone to bed on.”

Seemingly, the world had had gone mad overnight. But how had this happened? And what had caused this strange insanity?

Russell wanted to understand what the fuck had just happened. He also wanted to do something about this new topsy-turvy world, where the lunatics had taken over the asylum. He was finishing work on his documentary feature Freedom for the Wolf. Nick Fraser, the editor of BBC’s Storyville, had come onboard as executive producer. Fraser had also just launched a new venture, Docsville, and asked Russell if he would like to make some short films for this new platform.

On the day after the election, Russell had written a Medium post on being sane in insane places inspired by the work of David Rosenhan, in particular his famous experiment in which he entered an asylum claiming he heard voices. The doctors and nurses had diagnosed Rosenhan as insane, however, the patients quickly realized that Rosenhan was actually faking it.

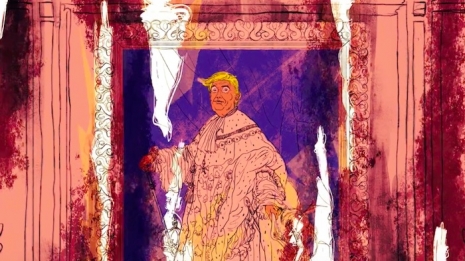

Russell also “sketched out two more essays on madness under the new regime of (in)sanity”. He sent these along to Fraser as a possible idea for a series of animations called How the World Went Mad which would diagnose Trump’s election as a form of madness and offer up a possible cure. Fraser told Russell to go for it.

The end result was a series of five short films explaining How the World Went Mad by which Russell asked the very pertinent question:

In a world gone mad who can you trust?

Beginning on that fateful morning in Fall 2016, Russell takes the viewer through a brief history of psychiatry, culture, and politics to explain how we have all ended up here. I contacted Russell to ask him about the making How the World Went Mad and what he hoped his diagnosis of our current malady would achieve.

How did you go about making ‘How the World Went Mad’?

Rupert Russell: I spent a month in the British Library going through histories and psychologies of madness. I picked out studies that could be linked together to form a narrative arc of the series: diagnosis, symptoms, transmission, epidemic, and cure. I turned the notes into scripts, recorded them, and sent the files to Dare Studio in Poland, who had worked on my last feature, who got to work on the animation. The rest is archival footage, which I trawled through.

The most arduous of which was finding out who the infamous “fat guy” that Trump tormented in The Apprentice was. When we locked picture, Alex Williamson composed a wonderfully off-kilter score and three sound designers at Unit Post created a soundscape of insanity filled with screams, explosions, and even orgasms.

The polemic for your films rests on the idea Trump is mad—what happens if he is not mad?

RR: The source of my anxiety, as I describe in Episode 1, “Diagnosis,” is precisely this question: What if Trump is the new definition of sanity and it is I who am in fact mad. The line between sanity and insanity has been a skipping rope throughout history, pulling people in and out of it. Gays, lesbians, and women have only recently escaped their 19th-century diagnosis as perverts and hysterics. The Trump/Pence victory signalled another swing of the rope. In their Handmaid’s Tale morality, these gender traitors deserve no voice in the patriarch’s definition of sanity—where only the male “commanders” are capable of rational judgements.

The insanity of this position should be self-evident. But too increasingly, it’s becoming the new definition of sanity. We are living through another reaction to social progress that has resurrected the same tropes and characters of the feminist backlash in the 1980s, which inspired Atwood’s original novel.

What if Trump is the naked representation of the lowest and baser side of populism in politics? Is he just the base and charmless reality of most politicians and governments?

RR: In the fabled Before Times, no politician—let alone Presidential aspirant—would refer to Neo-Nazis as “good people.” They would have been hurling themselves off the cliff of sanity into the abyss wondered by the lonely, babbling Birchers and the Truthers. But no longer. Now calls to “ban all Muslims” reap rapturous applause from voters. Xenophobia doesn’t have the ring of crazy anymore. The damn of sanity as ruptured.

As Nigel Farage said the day after Brexit to the European Parliament, “isn’t it funny…When I came here seventeen years ago and said I wanted to lead a campaign to get Britain to leave the Europeans Union, you all laughed at me. Well you’re not laughing now.”

Is it fair to suggest the same analysis could be applied to any leader or government? If not, what makes Trump different? What makes Trump so insane and so dangerous?

RR: It is true that the damn of sanity has broken all over the world and flooded our electoral bodies with crazy. But the maddening of our politics has been happening in parallel to the maddening of our media. It’s no coincidence. In the 1970s, it was obvious to Paddy Chayefsky as he wrote the prophetic Network that the quest for ratings would lead us to a place where psychics would predict the news on TV and terrorist groups would have Hollywood agents negotiating their reality show deals. And since the medium is the message, and elections are now experienced through television, it was inevitable that the quest for votes would become the quest for ratings. Trump’s genius was to grasp this shift and act on it.

In some ways, it’s a continuation of the tactics of past Republican presidents. We had the Reagan Show. George W. Bush cast himself the hero in a Jerry Bruckheimer movie. Trump went far further. He’s simultaneously the show’s producer, narrator, protagonist, hero and villain.

What makes Trump so dangerous is that he sees politics as just television by another means. Reagan and Bush used the tropes television had spread throughout popular culture to advance their agenda. For Trump, the ratings are the agenda. So he has an in-built incentive to raise the stakes, be unpredictable, and do something crazy you just have to tune in. Unfortunately, attacking minorities and threatening war achieve these goals better than anything else.

Where do you think this will lead the world?

RR: We’re amusing ourselves to death. Thanks to the global ubiquity of smartphones, we’re now more bored than we’ve ever been. We expect constant stimulation, constant amusement. When you go to Internet/phone addiction rehab, the most important lesson they teach is how to deal with “microboredoms.” Those 30 seconds waiting at a traffic light when people reflexively pull out their phones to fill the micro gap in their day. We also know from psychology that idle hands do in fact make the devil’s work. Boredom gives rise to alcoholism, drug abuse, domestic violence, unemployment, juvenile delinquency and racism.

Trump’s practice of politics as entertainment has come at precisely the right–or wrong–moment in history. Unable to deal with 30-second gaps in our lives, we turn to anything to entertain us. And what a show Trump is putting on. I think what we struggle with is realizing that we aren’t just observers but characters in this show. And our fates are determined by the quest to ensure that the ratings for next years season are even higher.

What do you hope viewers will learn from your films?

RR: Catharsis! I hope they learn they’re not alone in questioning their sanity.

Watch Rupert Russell’s superb series of short films How the World Went Mad here—subscription required.