Ticker-Tape, Rishi Dastidar (Nine Arches Press)

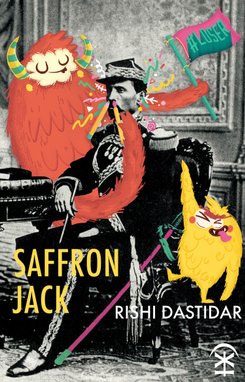

Saffron Jack, Rishi Dastidar (Nine Arches Press)

The covers of these titles jumped out at me on a recent visit to Foyles in London, especially Saffron Jack, a hallucinatory image of cartoon monsters hanging off a self-important military officer perched on an antique chair in epaulettes, fancy hat and medals on his ITchest. Rishi Dastidar is a new name to me, and if I am a few years late to the party I only have myself to blame, but am happy to play catch-up.

Ticker-Tape, the earlier of the two volumes I bought, evidences a poet torn between lyric impulses, politics and comedy; and one who is also an expert at list poems. Dastidar isn’t afraid to address racial and sexual politics, but is also prone to trying too hard to accommodate both the lustful male gaze and attempts to undercut it:

We are the girl boy you never slept with | that you want to forget |

We put and rattle to infinity | Can we objectify you yeah |

This imperative mood is infectious | This imperative mood infects us |

This is a manifesto for us | This is a manifesto for the cosmic us |

(‘The Girl Boy Black White Urban Desert

Digital Blue Rhinestone Drone Desire’)

It’s all a bit too knowing for me (‘the cosmic us’?), although I wonder if it might work better in performance? Here’s a monologue, ‘Licking Stamps’, from someone addressing ‘painter boy’ and how he might perceive them as a sex object. Having declared that they ‘don’t want things like “fireworks” / or “starlight” either’, the narrator concludes:

I know, I’ve got it. How about

fucking me is like licking stamps?

Sticky, time consuming and capable

of taking you to destinations exotic and

mundane. Yes, I’d like that very much.

We are clearly meant to laugh at the overstretched simile, but at the same time it is an overstretched simile. Dastidar is on better form in the overlong title poem, a long litany of… well, everything that makes up ‘My city. My belonging. I am waiting to fill it in.’

‘#MyEngland’ is not only (much) shorter, but also more successful as it lists and juxtaposes a series of the English’s assumptions about themselves, highlighting how ridiculous it all is. This poem is part of a short sequence, ‘Pretanic’ which also includes poems like ‘The British genius’, ‘Diagnosis: “Londonism”‘, ‘Strategies to save the Union’, and the brief final poem quoted here in its entirety:

The problem of becoming English

wasn’t, as I was supposing,

of whether the ethnicity

would accept my race;

but rather one of posing

in a top hat for publicity.

Elsewhere, as the book moves towards its back cover, Dastidar uses redaction and satire to good effect (‘I am an expat. / You are a refugee. / They are a migrant.’) but also offers a softer, more romantic voice, although unfortunately one still subject to using terms like ‘she-god’ and ‘babe’.

Two books later, and we find Dastidar using a Wittgenstein-ian numbering system to construct a whole book about Saffron Jack, self-appointed ruler of his own nation, intent on ‘cocking a snook at the existing nations’ and excluding everyone else. Slowly the 193 sections (plus interruptions) of cod-philosophy and comment combine to construct a devastating commentary on self- and nation-hood, on belonging and rejection, on exclusion and inclusion, racism and hate.

Just as the realities of being king or dictator start to kick in:

23. You do not get into the kingship racket to make a

fast buck.

23.1. There are better ways to make some

money –

23.1.1. or a living

23.1.1.1. or to stay alive.

so too does recognition of cultural assumptions and expectations from others, even your own family:

160. But the assumptions, always the assumptions.

160.1. No, you are not from here.

160.2. No, you were born here.

160.3. No, you have not been.

160.3.1 Sure, maybe, why not, no plans.

160.4. No, you are not all friends.

160.5. No, you do now all know each other.

160.6. No, you are not an accountant.

160.7. No, you are not an doctor.

160.8. No, you are not a lawyer.

160.9. No, you do not work in a corner shop.

160.9.1. And your parents do not either.

160.10. And no, you do not like Bollywood and

you fucking hate curry.

Even as we (and Saffron Jack) slowly come to terms with our own racism and exclusionary politics (‘186. Now you get it.’) were are told ‘If you are waiting for a moral, do not.’ (192) There is no moral, just a car-crash of self-serving delusion and self-mythologizing that ‘has made you what you are. The hollow wreck / that you are.’ (191) And meanwhile

WE HAVE INVADED YOUR COUNTRY.

STOP.

This is a digressionary, witty, provocative and indeed revolutionary, critique of the idiocy of contemporary politics, warmongering and neoliberalism. Dastidar points the finger at all of us, including himself, without preaching or offering any trite solutions. It is the best book of poetry I have read for a long time, and I look forward to getting the author’s next book when it comes out rather than several years later.

Rupert Loydell