Reviewing Peter Brook and Marie-Helene Estienne’s THE PRISONER

National Theatre , September 17th 2018

As the dream fades,

What we recall of that intangible aspect

Or essence that first claimed us through sleep,

Lingers,

As if painting the air.

Just such a legacy permeates both theatre, audience and consciousness after tonight’s production, the latest fruit from theatrical grand master Peter Brook’s Theatre des Bouffes Nord’s great tree of truth to fall and settle, having breached the all too real waters of detachment and conflagration that continue to separate us from the once calming European traditions from which we were first formed and found.

Storytelling in its purest and most metaphysical state lays at the heart of this beguiling masterwork in comparative miniature, (the play lasts just over an hour) as it relates the tale of Mavuso, a young man from a ‘far country,’ guilty of passion and sexual engagement with his beautiful sister Nadia and the subsequent murder of their father, after he discovers their blood sparked conjugation. Taken in, solaced and in a spiritual sense given succour by his uncle, Ezekiel a local wise man, Mavuso’s fate is argued over and his sentence transmuted to remaining an inmate of the outside, condemned for an indefinite period to simply staring at and contemplating the meaning of the prison that would otherwise confine him. As we witness the myth fired events that lead to this situation we are aware of the journey Brook and Estienne have taken throughout not only the many years of their collaboration, but clearly their lives as a whole. From Brook’s The Ik, Conference of the Birds, Mahabharata, through to his and Estienne’s Je Suis Une Phoenomene, The Suit and The Man Who, the work has been consumed with both defining and distilling what true theatre is and can be.

Each production has utilised powerful spectacles of economy with elegant poetic structures and techniques that date back from theatre’s cave fed origins through to the full range of classic and contemporary european, african and asian studies of shadow and skin. That these are married with the cutting edge of contemporary practise and a great deal of philosophy,contemplation and reflection makes them all the more affecting and important to those of us marooned in the jaded digital age, sourced as it is from an all too worldly sense of deceit, abuse and ignorance.

Each of the 29 episodes that comprise Mavuso’s story, encapsulates the nature of survival, endurance, and an absorption in the self of the kind that can only lead to revelation. Brook’s theatre is concerned primarily with the actions of the soul upon the body and no doubt vice versa , as he uses the spaces he casts and peoples as a form of mirror, reflecting back to an attentive yet challenged audience their unglimpsed potential beyond the confines of their all too familiar world.

As Mavuso undergoes trials of being while remaining bound by the outside air, his inner spirit wrestles with all he is confronted with. He befriends a rat in his splendid isolation and soon eats it. He continues to learn at the foot of his master Ezekiel and he begins to understand his profound desire for Nadia, as the supposed license and versatility of his sentence speaks ultimately of his and indeed, our inner need for punishment. In this way, The Prisoner, like Patrick McGoohan’ psychology to psychedelic television masterpiece of the same name teaches us of the ways and means with which we submit to capture, all the while exposing the fact that the structures we create around us in western society at least, are the smoke from a far greater fire, eating away at the splinters and rope in our hearts.

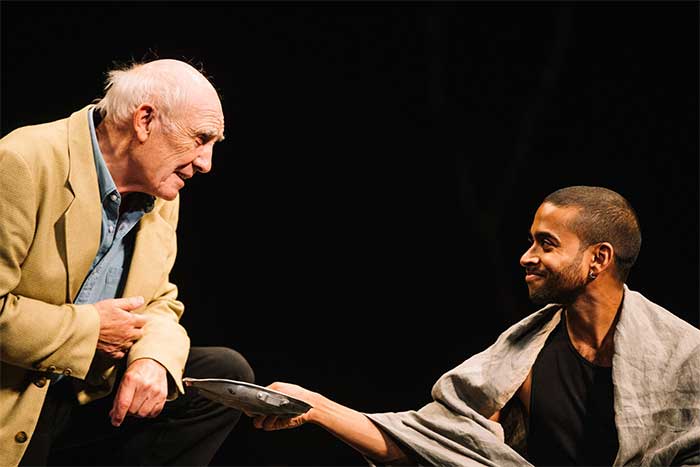

Brook and Estienne’s achievement is to educate without hectoring. They do this through the power of their theatrical craft and the enchantment they have been able to capture and transform into an almost visible music and sense of magic in both the design and otherworldliness of their approaches to art as it is meant to be observed and no doubt, lived. Simplicity and a lack of ceremony becomes a ceremony in itself, a controlled form of ritual and an endeavour to be savoured; a meal finessed from the most nourishing and natural ingredients. The cast, comprising a wonder sparked Hiran Abeysekera as Mavuso, Herve Goffings deeply responsible and charismatic Ezekiel, an earnest and pure hearted Kalieaswari Srinivasan as Nadia and a fish intoxicated guard, Omar Silva as the decapitating and ultimately despairing Man from the village and a far more fearsome form of guard, and England’s own great theatrical mainstay, Donald Sumpter as a hugely appealing Visitor to the story and thus embodiment of our own interest and understanding serve each breath and moment with the utmost of commitment, mining all aspects for the gold of significance. Brook, Estienne and the artfully simple lighting of Philippe Vialette that effortlessly conjures the passing of time embue each aspect of The Prisoner with an eerie and equally effective sense of authority. At the same time the need to be as simple, direct and as open to each of these elements and gestures as a still searching pilgrim or child in the enveloping dark is wonderfully persuasive.

The play opens as a conversation, a relaying of events, unfolding as a viable alternative for man’s time and earth, and therefore becoming a much longed for truth. The play and the decisions that comprise it, appear out of a kind of haze, but attain an immediate clarity, as can be seen on the page of the published performance text and on the stage of the Dorfman theatre as the masterful ensemble conjure these characters from an air of solid saffron and umber.

The stillness was practically visible and the meditative state that the play enduced in its audience was itself a reflection of the clarity of intent on display. Poetry was brought into play between those watching and more importantly, listening and those experiencing the depicted events. Suggestion becomes action and the mystery deepens and in so doing, touches all in the room. If actor and audience can on some level combine than art as I understand it, is achieved. One can be too sacred of course but with the dignity embodied here the balance was powerfully observed.

The play’s length as mentioned previously, is a testament to its theatrical potency. Many modern plays now run to this length and labour under the illusion that they deliver through brevity either a universality or sense of directness. Unlike the great One Act Plays of the post war years, that brevity is not evidence of succinctness of poetry, certainly not of the sort that rivers through Pinter, Beckett, and the increasingly astounding Caryl Churchill. The Prisoner honours that former tradition because like the best art it makes its frame part of the painting itself. Its form is necessary in order to achieve the enchantment we do not always know we are searching for, and precision and indeed concision are the point, as opposed to the transitory passions of the fashionable and the flip. Like the best poems the work is a kind of clenched fist, flowering into an open palm, that offers its prized and precious aspect to us, rather like the beggar offering the bowl in the visitor’s opening monologue. Sumpter’s Visitor is our host, a narrator on one level, (while also visually suggesting a surrogate Peter Brook), but also a bridge between the worlds we inhabit and those that unknown to us, we all continue to aspire to and dream of.

On a set of bark, bone and stone the world is repeopled. Sumpter’s low opening energy allows us easy admittance and there is a grace to be found in the lack of grace evident as events unfold in an unadorned and factual manner. After his legs are pierced with a branch, Abeysekera’s walk of recovery combines man and nature, as he uses the very stick that speared him to enable his recovery , just as his mercurial and athletic climbing onto the theatre balcony gloriously shows his wonder at being led into a forest made of actor spun whistles and clicks in anticipation of his spiritual confinement. It is a last shot at life before his own target closes and the lightness is wonder is once again, visible.

As Nadia healed his wounds with traditional song, so the ghost of his murdered father returns when Mavuso reads his father’s book, gifted to him by Ezekiel as exile’s study text. These sacred moments inform all of Brook’s work and yet license has been granted for humour and extemporisation beyond the text as Mavuso comforts the rat he creates with hand movements under his blanket and Sumpter’s guard contentedly satyrs away to his young companion. But chief among all these things is the need and value of transcendence. The prisoner will not finish his sentence until time itself has spoken, and as the country diminishes around him and the prison also deteriorates, life is reduced to the bare essentials in every sense.

Survival is all that matters and its hardships and rituals form an internal prison containing its own freedoms and codes of initiation. The length of a legend is as short as a phrase and as endless as a sentence containing the development of our own unravelling sense of identity and expression. If the air is not recognised as the intended reflection of all it is possible for us to achieve, then it cannot be fully tasted or ever form part of our ascent and connection to the world and environment we would master. Here, then, we find amidst a search for sensation and a true quest for meaning, the child who learns darkness is its own kind of light.

Harness the world and it soon gives way to another.

As the prison door opens,

We find in a cell made from sticks, stars, stairs and stirrings,

Ways in which magic gives those who were blind true insight.

images by Ryan Buchanan

David Erdos 17th September 2018