‘Wayn maktab sahaafa Hizbollah?’ I asked a smiling man on the street. He had noticed that I was looking lost despite the Google Map coordinates telling me I was right outside the Hizbollah press office in question. The man enthusiastically led me into a building located a few yards ahead of us, five flights of dull concrete typical of many Beirut apartment and office blocks. ‘Third floor,’ he said, pressing the lift button for me and then waving goodbye as I ascended.

I was to meet Mohammed Afif, a journalist, and Hizbollah’s leading media spokesman, in his latest office. This one was located on Mouawad Street in the heart of Dahiya, the party’s southern Beirut stronghold. The last time I met Afif was in another Dahiya location some seven years earlier. His young female secretary had on that occasion provided the tea and the highly efficient translation, seemingly without pulling any of his punches. This time around her replacement, let’s call her Nisreen, welcomed me from a half-open office door opposite the lift. Nisreen seemed to have been only tasked with ensuring that I, the latest western writer to make their way to Mr Afif’s door, had physically got there and that, once inside, was made comfortable.

A recognisable reporter from a renowned US newspaper was waiting too; he with his Lebanese assistant. The US reporter and me exchanged wary words. I feared one of those competitive pooled media interviews but felt a lot more relaxed when Nisreen, reading my face, informed me that my audience with Afif would be in private. As we all sat and waited together, Nisreen asked me to tell her about the International Times; other foreign news titles with the word ‘Times’ in their title were presumably more familiar. In this Beirut press office of the leading resistance force in the region, Nisreen was wondering what exactly the ‘Magazine of Resistance’ was all about. I awkwardly began to mutter something fairly incoherent about a long standing British publication of cultural and political affairs, when to my relief we were interrupted by a call from Mr Afif’s inner sanctum.

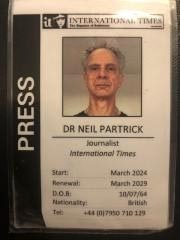

Having a physical press card still remains important for foreign writers wanting to meet state officials in many parts of the Arab world. As a freelance writer I don’t have one. So a few months earlier International Times had allowed my partner, the artist Valerie J Grove, to literally construct the press card that helped facilitate this meeting with Hizbollah. This was originally done as part of my visa application to northern Yemen, stronghold of fellow anti-Israel resistance force, the Houthi. The Houthi, who run much of the Republic of Yemen, never questioned who or what International Times was. However my visa approval from the Yemeni capital Sana’ was not forthcoming. The same concocted IT press card had also been photographed by officials in the Syrian embassy in Paris, while an almost smiling and decidedly younger President Bashar Al-Assad looked down on proceedings from a framed portrait. He said no too.

On a mission to explore the strength and weakness of the Arab majority states, not least in Lebanon, I had photographed the IT press card and my passport ID page and then WhatsApped them to Mohammed Afif two weeks before my arrival in Lebanon. I noted the irony that Hizbollah, a political and armed Shia Islamist group only modestly and indirectly represented in the then Lebanese government, and aways denying that its militant arm undermined the sovereignty of the official state, required the same press and personal ID that the Lebanese Government insisted on. Then again, this meeting was being held eight months into the regional war that had followed the Hamas attack on Israel on October 7 2023. Israel had been intensifying its air and missile strikes on Lebanon ever since, whilst a greater Israeli onslaught on Lebanon including ground troops seemed likely to follow shortly. You would expect security to be tight, wouldn’t you? Tighter than my own fairly effortless entrance to the building in which Mohammed Afif and his Hizbollah assistants dwelt.

Engaging as ever, Afif clasped my hand warmly. He smiled genially as we exchanged broken Arabic and English small-talk. There were at least five other men sitting with him. All, like him and me, bearded and besuited. I am always nervous on such set piece occasions, regardless of who my interlocutors are.

After more tea drinking formalities, Afif announced in English that ‘We are on the record,’ but politely emphasised that he would like to see any quotes attributed to him before publication. I turned to my list of scribbled questions, kicking off with a fairly predictable and easily deflectable enquiry into how much Hizbollah’s ongoing ‘Gaza support war’ was actually an extension of Iran’s forward deterrence. Afif then quickly switched to Arabic. A smiling, gentle man immediately to my right on our small shared sofa began to relay all of Afif’s extensive response in a highly mannered but efficient English. Nisreen had disappeared.

We are a Lebanese national movement, Afif stated. Our heroic resistance liberated Lebanon from Israeli occupation in 2000. That historic Israeli pullout, ending a near 20 year military regime that Israel had constructed in southern Lebanon, was arguably Hizbollah’s Lebanese and regional political trump card. This liberation was he said a Lebanese national act conducted by our movement. Yes, he admitted, Hizbollah’s formation was originally promoted by Iran, but as a solely Lebanese resistance movement to free the country from Israeli occupation.

Afif gave me none of the usual Lebanese rhetorical reference to the ‘still Israeli occupied’ Lebanese territories. These territories sit at the meeting point of Lebanon, Israel and the Israeli-occupied Golan Heights; namely the farming lands of Shebaa and the strategically valuable village of Ghajar through which the River Hasbani runs into Israel. These still disputed areas, at least partly Lebanese but not in the eyes of the UN who label them Syrian (except Israeli-held ‘northern’ Ghaja), did not interfere with Afif’s discourse on Hizbollah’s proven and successful armed commitment to the Lebanese national cause.

I detect opposition in other parts of Beirut to your current war with Israel, I told him, noting the distinct absence of Palestinian flags in the Christian areas in contrast with the broad swathe of such highly visible solidarity expressions in for example the mixed but Shia majority Dahiya. Afif responded that the Lebanese Christian community is varied in its attitude to Hizbollah’s armed actions. In our 2006 conflict with Israel there were Lebanese voices opposed to Lebanon being at war then. This time it’s different, he said. There are many Lebanese who welcome our defence of Palestine even if its flags do not flutter in some parts of the capital. There are some Christians who want a relationship with Israel, Afif conceded, but there are many more who oppose it. All opinions are heard in the Lebanese parliament and on the Lebanese street, Afif added.

Mohammed Afif laughed at my suggestion that Hizbollah forces were still present in Syria, supporting the Assad regime against ISIS, as he had described the movement’s original intervention in its neighbour’s territory. However Afif emphasised that should Israel further expand its regional war then Hizbollah could return to Syria. Afif said that the war against Israel that was being fought by Hizbollah from Lebanese territory could easily be conducted from inside Syria, even inside the Israeli-occupied Syrian Golan Heights. If there is ‘[A]ll-out war it may be possible that Hizbollah would deploy to Syria, for example to the Golan Heights,’ he said. From there Hizbollah could, he said, head south. ‘Events might happen, a breakthrough’ i.e. an Hizbollah armed push inside Israel proper. Afif noted that the ‘rules of engagement’ that it and Israel had observed with each other, buttressed by third party mediators, ever since the previous war in 2006, and previously, had now broken down. He foresaw that an end to Israel’s war on Gaza could be followed by Hizbollah’s ‘delegates’ meeting with the USA to broker a return to what traditionally had been its managed Hizbollah conflict with Israel. ‘If we meet again in a few months then maybe things will have changed,’ he said to me smiling.

This was the 16th of May 2024.

On November 17 2024 Mohammed Afif was killed, having been deliberately targeted in an Israeli air strike on, of all things, a building belonging to the Lebanese branch of the Ba’ath Party, still the ruling party of Syria at that time and formerly of Saddam Hussein’s Iraq. Hizbollah’s relations were no doubt more than cordial with the pro-Syrian Lebanese Ba’ath, but ultimately Israel only cared that this was where Afif was going to be located that day. By this stage Hizbollah leader Hassan Nasrallah, the successor to Abbas Musawi with whom Afif had been close, was already dead, along with many other leading Hizbollah figures, including those killed and injured in the infamous coordinated Israeli mass mobile phone explosions throughout the country.

Things had indeed changed.

Israeli ground troops were now engaging in their own disarmament of Hizbollah in southern Lebanon, following the systematic bombing that had forced many Lebanese Shia, including Hizbollah supporters, to Beirut and even to Sunni areas in the north of the country. Afif had laughed too at what he called my ‘journalist’s question’ about Hizbollah negotiating a deal whereby it stalled the conflict with Israel by agreeing to disarm in the south. He emphasised that what he claimed has been a non-armed Hizbollah presence in southern Lebanon before October 7 2023 as part of the 2006 ceasefire deal, was now a series of Hizbollah military camps set up to resist the expected invasion of Israeli troops.

Israel’s unleashing of a full scale war on Lebanon in September 2024 seemed intent on not only dismantling that Hizbollah armed structure but on coercing the Lebanese state to conduct a disarmament of Hizbollah throughout the whole country. Israel bombed Sunni and Christian areas with whom it was ostensibly not at war, seeking to terrorise these Lebanese into pressuring the Lebanese state into action against Hizbollah. Ironically, just ten days after Mohammed Afif, the official voice of Hizbollah, had been extinguished by Israel, a US-brokered ceasefire was negotiated by the Biden Administration. The November 27 2024 ceasefire agreement was an Israeli-Hizbollah deal brokered by the US’ Amos Hochstein with Hizbollah’s closest Lebanese ally, the speaker of the Lebanese Parliament Nabi Birri.

Like the October 10 2025 Israel-Hamas ceasefire deal in Gaza, the Israel-Hizbollah ceasefire agreement was not signed by the belligerents themselves. This understandable inability to lend your enemy the legitimacy of such ‘recognition’ emphasises how much these ceasefires are in essence just that: ceasefires. In Lebanon as in Gaza, Israeli occupying troops are left in situ, committed to eventually withdrawing but only as part of an open-ended process that requires the armed force that has local legitimacy in the territory Israel has occupied, to disarm under threat of Israeli fire. Hizbollah to a greater or lesser extent, has now been disarmed in the south of Lebanon in a peaceable process conducted in coordination with official Lebanese state forces, from the Israeli border right up to the agreed line of the Litani River. Even such a partial disarmament process is much harder to envisage Hamas doing in Gaza in favour of the proposed International Stabilisation Force, whether with Arab states’ active participation or not. Coercion by fellow nationals, let alone foreigners, western or Arab, is in either case a non-starter.

Israel is still demanding that Hizbollah be fully and totally disarmed throughout Lebanon, something that the Lebanese Army can only do by consent not the force that Israel publicly expects and which few senior Lebanese across the political and sectarian spectrum, or even President Trump’s officials, think realistic. Consequently Israel has not moved from the five locations inside southern Lebanon that it relocated to as part of the November 2024 ceasefire. In an augury of where things may well go in Gaza, Israel periodically strikes targets from inside Lebanon that it alleges are related to Hizbollah’s armed capability. While Israel may need to be a little politically cautious in the immediate aftermath of President Trump’s vainglorious peace pretensions, it will reserve the right to break the ceasefire in Gaza out of claimed security exigencies, just as it has been doing in Lebanon for the past year. Just in fact as it has increasingly been doing, without any notional ceasefire, on the West Bank since October 7 2023, including forcibly displacing some of the northern West Bank Palestinian population in the context of Israeli airstrikes and ground attacks conducted in parallel with the territorial expansion of semi-state militia otherwise known as Israeli settlers. This is not to deny that the West Bank has both Hamas and PLO-related anti-Israel armed militants who seek to kill Israelis. However the scale of Israeli state and semi-state armed action in the West Bank is about more than Israeli self-defence, just as its wars in Gaza and Lebanon have been. On the West Bank Israel is patently erasing the statehood ambitions of the Palestinians. In the unlikely event that Trump’s vague 20 point ‘peace plan’ actually succeeds in Gaza, then perhaps that Strip alone will become the Palestinian state, truncated and without key features of sovereignty, that western powers and Arab states seems to be interested in again.

In Lebanon, Israel seems likely to retain coercive options vis-à-vis Lebanese state forces that, despite Hizbollah’s reduced capability, cannot assume control of national territory, a situation hardly aided by the seeming semi-permanence of the renewed Israeli occupation.

Sadly Mohammed Afif did not live long enough for me to be able to check my quotes with him. He is though widely quoted in both the Lebanon and Syria chapters of the book on state failure that I eventually got published*. He died knowing that Hizbollah had been significantly reduced in armed capability by Israel, whether in leadership terms or in materiel. It remains practically and politically unable to act with the scale of armed capability against Israel that might resume the relative balance in strength of the so-called rules of engagement that he had told me could return. Either that, he said, or all-out war.

Almost to the day that the Lebanon ceasefire was agreed, the Syrian regime that Hizbollah had defended and that had provided a key strategic conduit for Iranian arms westward to Hizbollah, began to collapse. A barely functioning Syrian state essentially went with it. A few months later Israel, with US air force assistance designed to both degrade Iran and, paradoxically, control Israel’s political ambitions there, bombed Iranian civil nuclear and other key sites. However, in Lebanon at least, Hizbollah is not politically cowed.

On September 27 2025 it defiantly held a mass rally in Beirut marking one year since Hizbollah leader Nasrallah was killed by Israel. The ‘martyr’ Nasrallah and his successor’s image were projected together onto the iconic Raouche Rocks. By doing so Hizbollah made the Saudi and western-backed Lebanese premier Nawaf Salam, who had tried to ban such ‘anti-state’ activity, look impotent as the official Lebanese police and army ignored his request that they break it up.

Hizbollah remains the major political patron of the Lebanese Shia community, and while its resources and armed supply lines are constrained, it remains the pre-eminent national Lebanese political player. It has not gone from the south of Lebanon either. Removing men in uniform does not, as will be evident in Gaza, remove an armed capability opposed to an ongoing Israeli presence. Hizbollah does not need armed camps to remain important in the south of Lebanon, as well as in the Bekaa Valley bordering Syria and parts of the capital Beirut. On a visit south to Tyre (Sur) in late May 2024, the site of sustained Israeli bombing less than five months later, a Lebanese secular Shia noted a network of social privilege that Hizbollah provides for its supporters in this historic and beautiful Mediterranean city, and throughout the south. A Hizbollah loyalty card, she noted, buys its followers subsidised goods and services, and access to Hizbollah’s private schools.

My travels throughout the rest of Lebanon, meeting sectarian leaders, activists, and a significant number of exiled Syrians waiting for the fall of a Syrian regime that, unexpectedly, shortly followed Israel’s war on Hizbollah, had shown me that social and political fundamentals, often brutally ‘sub-state’ and competitive as much as ‘national’, would not be dislodged by external attack. Loyal articulate individuals without a role in the fighting, like Mohammed Afif, will sadly continue to be killed, but the struggle will go on. This lesson remains relevant in Lebanon and in Palestine, and indeed in Israel where religious nationalism is consolidating the historic territorial ambitions of the more cautious secular Zionists who no longer lead that state’s policy.

Without my International Times press card I would not have been able to tell Hizbollah’s part of the Lebanese story and for that I am very grateful.

Neil Partrick

*‘State Failure in the Middle East – Syria, Lebanon, Iraq and Yemen’ was published by Routledge in August 2025.

Mouin Rabbani, co-editor of the ezine Jadaliyya, wrote: “This book is an essential addition to the literature on the contemporary Arab state by a scholar deeply immersed in both the subject and the region. The extensive reliance on Arabic sources, and numerous, incisive interviews in particular, is a particular strength.”

Dr Mohammed al-Rumaihi, Kuwaiti journalist and government adviser, wrote in Al-Sharq Al-Awsat, “The value of the book lies in the author’s interviews with a number of current and former officials, advisors, analysts, and experts, both Arab and non-Arab, to present a more realistic picture than mere theoretical analysis. It is a valuable addition to the region’s affairs.”

Dr Hussein Ibish, Senior Resident Scholar, Arab Gulf Studies Institute, commented: “Anyone seeking to understand the cascading disasters in the Arab world need to look no further than this crucial volume. It is an indispensable addition to the literature on one of the world’s most important yet troubled regions, and will remain required reading for decades.”

.