GEOFF Nicholson is a distinguished and acclaimed English writer, born in Sheffield in 1953 and educated at Cambridge, who has taken an interest in topics of travel and movement in more than a 15 novels and delved into topics such as Andy Warhol and Frank Lloyd Wright in his prolific non-fiction output.

His interest in that Beat Generation moment is evident in many of the themes – the road and cars, specifically Volkswagens – that pervade much of his work, which has attracted critical recognition along the way from novelists such as JG Ballard, who called his 1987 debut novel Street Sleeper ‘witty, zany and brilliantly comic’.

Ballard was a man with a taste for sci-fi dystopias in ways that a fan of his, William Burroughs, shared. Yet Nicholson is a more sardonic, amusing commentator than that lofty literary pair: his work relies on wit and whimsy, black humour even, more than psycho-ideology or despair at the arc of Western history.

Pictured above: Author Geoff Nicholson, image by Caroline Gannon

Yet if automobiles, guitars and the USA have more than hinted at his deep-seated transatlantic inspirations, Nicholson also displays a more down-to-earth concern – walking is both his passion and his cause, with the ‘Right to Roam’, a celebrated political campaign to set the British countryside free for hikers, high up his individual agenda. His latest title Walking on Thin Air: A Life’s Journey in 99 Steps considers these issues.

Our regular interviewer MALCOLM PAUL tracked down Geoff Nicholson to explore his views on the Beat writers and the musical threads that feed into his experience, personal and artistic. His responses provide a lively interpretation of the role of literature and rock and jazz in the working life of a cutting-edge commentator…

MP: I’d like to ask a few questions about your possible connection with the Beats and also the ways in which music has shaped your own creative landscape. First those writers. When you started reading adult literature. other than the books of the time, did you encounter books like Kerouac’s On The Road, Burroughs’ Naked Lunch or Ginsberg’s ‘Howl’?

GN: Yes, the Beats were the first writers I discovered for myself, Kerouac especially. I saw a copy of On The Road when I was hitchhiking around France – at the time Kerouac was considered to be the patron saint of hitchhikers, so I bought a copy and I was hooked. Don’t quiz me on it but I think I’ve read all his fiction.

I had my first glimpse of Burroughs even earlier. I went to a rather grim grammar school but one or two of the English teachers were cool. We were shown it was OK to read things like Lennon’s Spaniard In the Works and the Liverpool Poets. A teacher named Bill Scobie mentioned Burroughs’ Dead Fingers Talk, which he said was strong stuff but he thought we could handle it.

Naked Lunch was the first Burroughs book that I read, then Junkie, then The Soft Machine, largely because I was a fan of the band. I did write a dissertation as part of my final university exams on Kerouac and Burroughs – though Henry Miller and Anaïs Nin crept in there too. The dissertation had something to do with adventure and experiment – in the lives and in the writing: Kerouac’s ‘spontaneous prose,’ and Burroughs’ cut-up and fold-in methods.

I was less of a fan of Ginsberg. I sometimes say I have a blind spot for poetry but it’s not absolute. I was a fan of the Liverpool Poets – especially Brian Patten. Do they count as Beat? The Beats seem to be an essentially American phenomenon but of course the influence spread far and wide. At university I was taught by the poet JH Prynne who was a champion, and I think friend, of Robert Creeley, Charles Olson and Ed Dorn, so I certainly read those guys, Dorn especially

And I came very late to Gary Snyder. I saw him read in a tent at the LA Book Festival in 2005 or so and I was knocked out. I said at the time it was the best poetry reading I’d ever been to, and I haven’t changed that opinion. I did meet him afterwards back stage and I’d just read Iain Sinclair’s book American Smoke in which Snyder appears, though Sinclair’s portrait of him isn’t entirely flattering. Stuck for something to say I mentioned the book to Snyder and he said, ‘Oh yeah, that was a funny piece.’ I’ve never known if he meant funny ha ha or funny peculiar!

For a while I was ‘prose editor’ of the literary magazine Ambit, edited by Martin Bax. I had no say in the selection of poetry but Martin was full of stories about people he’d published, that included Burroughs but closer to home it meant Ivor Cutler, Jeff Nuttall, Ralph Steadman, Michael Horovitz, Michael McClure, Stevie Smith, one or two of whom I got to meet.

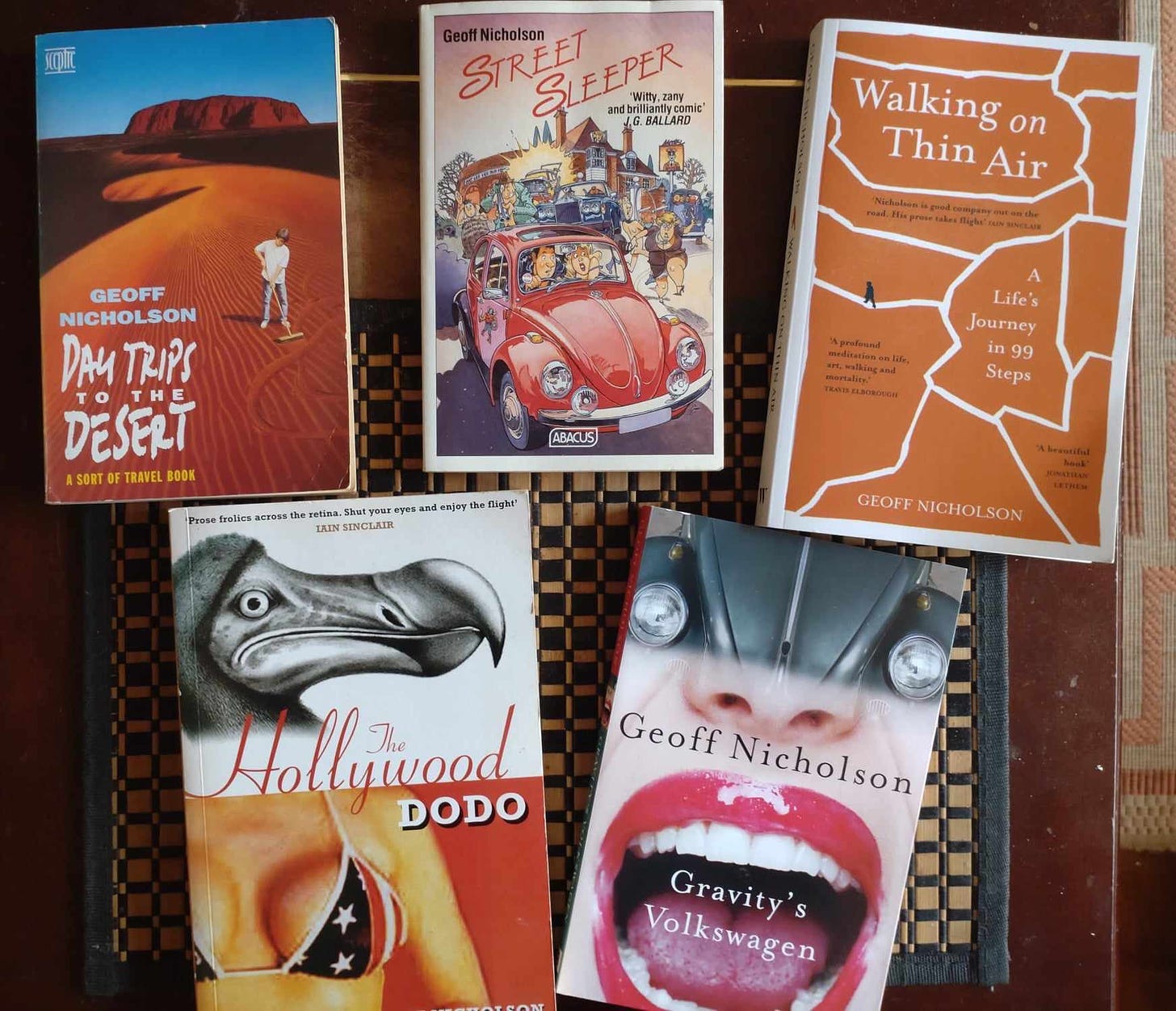

Pictured above: A selection of Nicholson titles

MP: If you did read these authors did they influence your writing style?

GN: I think an author is never the best judge of his own influences, but I’ll try. I started out writing plays – I wrote a couple of things that got put on at the London Fringe and the Edinburgh Festival, but I always had ambitions to be a novelist. My first novel Street Sleeper was an attempt to write an English road novel, and it was a satire of the American form. The lead character is trying to live out some of that Zen, Beat thing, and, although it was ironic, in my own way I still find that very appealing.

The Beats’ lives, with all their troubles, always sounded a lot more interesting than mine. Kerouac would go cross the country, meet up with Neal Cassady et al, and they’d go to a club and there’d be jazz and poetry and girls and reefers. I was envious.

There are also notions of transcendence whether through art or sex or religion or music, a recognition that ‘ordinary life’ isn’t enough. And then there’s drugs. I was never much of a druggy but I do find drugs interesting – as in Thomas De Quincey and Coleridge. And different states of consciousness were obviously a major part of the Beat/hippy ethos, but anybody who reads Naked Lunch and thinks heroin is a good lifestyle choice is obviously out of their mind (I have in fact met such people).

MP: Having your read your books, the one thing I think you share with the Beats – and it’s only my opinion – is that you are fearless in your plotting, unafraid to celebrate the fantastical and those who might exist outside of so-called normal society. To give the drifters and the washed up, marginalised folks all, a place in the scheme of things is something the Beats – especially Burroughs and Kerouac delight in. I think it’s the willingness to take a risk on a story or a plot that others might think too outlandish that you share with the Beats. Do you think that’s a fair comparison?

GN: Harold Bloom says somewhere that all great art is strange. Which of course is not to say that all strange art is great. I’ve never consciously decided to be ‘zany’ in my writing – it comes out the way it comes out. But it’s true enough that I don’t find ‘naturalism’ very attractive. I recently read Jane Eyre for the first time (there are a lot of holes in my reading) and it’s great but it’s weirder than hell, which I don’t think is generally recognized. And Jane Eyre, the character, isn’t just Beat, she’s downright punk!

MP: The Beats were/are often about seeking a freedom inner and outer – often by experimenting with drugs, sex and alternative lifestyles, dropping out, taking to the open highway. Do you think that like the hippies – let’s regard them as the Beats’ radical offspring – were just were a bunch of guys mainly on some kind of ego trip, often abusing others and, as critics have often pointed out, merely a bunch of narcissists whose idea of rebellion and a counterculture contributed little to life or culture. Alternatively did they actually galvanise the post-war generation into escaping the grey world that was America of the 1950s? Big question…

GN: Big question indeed. I think we do come back to the effect of World War II – Lawrence Ferlinghetti, who was in the US navy throughout the war, became an ardent pacifist. And why wouldn’t he? War was terrible; we should give peace a chance and all we needed was love. None of that, of course, is exactly controversial. But I think the early post-war generations had a sense that their parents were too serious, too materialistic, too scarred by the war; so let’s grow our hair, smoke dope and dance. There are worse strategies.

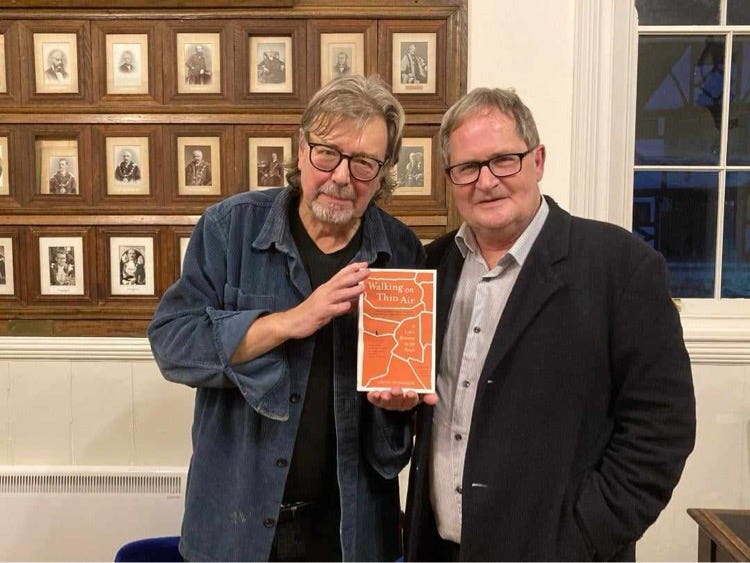

Pictured above: Geoff Nicholson with his interviewer Malcolm Paul at a recent Faversham Book Festival, image by Caroline Gannon

MP: Do you think that the whole idea of rebellion – attacking the establishment, being a radical is an outmoded concept. Did it die alongside the Beats, hippies, punks and so on? Does a countercultural revolution have any meaning or relevance today.?

GN: An even bigger question! Of course everybody’s a rebel when they’re 18. The fact that I did a certain amount of travelling, backpacking, hitchhiking when I was young, and was interested in art and literature and music, made me feel like there was a chasm between how I wanted to live and how my parents lived.

But then at some point I realised that when my parents were in their teens there was a war on, and my dad volunteered for the navy and he spent some years travelling the world, usually while people were trying to kill him. After the war, he was content to stay in his semi in Sheffield and have a week’s holiday in Blackpool every year. At some point that started to make perfect sense to me.

Of course we now have Extinction Rebellion. The desire not become extinct is again an uncontroversial and perfectly reasonable one. Whether throwing soup at the Mona Lisa at quite achieves that aim is another matter…

MP: As an author with a lot of life experience here and in the US, having written a lot about travel.in many different ways from Street Sleeper to Walking on Thin Air, be it on foot or whatever, does the nomadic lifestyle appeal to you? Or living in communities away from others perhaps? Maybe that is something you share with the Beats?

GN: There was the very briefest moment when I thought that living in a commune sounded great. My extended family were rollicking, argumentative Irish Catholics – and it was easy to think that RD Laing might be onto something with the idea that the family was the cause of a lot of trouble, even madness. Certainly in my own life I haven’t replicated that big rollicking family. It seems to me now that it’s hard enough living with one person: living with a whole commune would be hideous.

MP: Did you listen to lot of jazz when you were/are writing your novels? For instance, Street Sleeper and the Volkswagen series?

GN: As I was growing up jazz meant Acker Bilk and Kenny Ball. Only gradually did I realise it meant Miles, Coltrane, Monk, Parker. To a large extent I was introduced to it via rock music. There were a lot of jazzers who crossed over into fusion and jazz rock. I loved a lot of free jazz – Lol Coxhill, Han Bennick, the Spontaneous Music Ensemble and especially Derek Bailey (a man from Sheffield, like me). I was sold on the spontaneity and improvisation. The idea that you could just go up on stage and make it up as you went along was and remains incredibly attractive.

Frank Zappa was also a favourite. I liked the combination of virtuosity, high seriousness and low comedy. Jazz was part of his vocabulary and he worked with quite a few jazz players – Archie Shepp, Roland Kirk, Jean Luc Ponty. He opened my ears and a lot of other people’s too, I’m sure,

MP: Did you own a Walkman for walking? I imagine not…I personally hated missing what was going on around me then and now…

GN: I’m the same as you – the idea of being shut off from the environment while walking is horrible. If nothing else you want to be able to hear the car that’s about to run you down.

MP: If you listened to prog rock, can you share your favourites? I saw Yes three times in the 70s!! King Crimson. too…

GN: The first headline act I ever saw were the Nice – Keith Emerson leaping on his Hammond and sticking knives into the keyboards. I thought it was fantastic. In the late 60s early 70s a lot of touring bands came to the Sheffield City Hall and I saw anyone who came – Pink Floyd, Led Zeppelin, who weren’t all that great but maybe they were having a bad night. Genesis, King Crimson, Van Der Graaf Generator. And Lifetime – that was a hell of a night – Jack Bruce, John McLaughlin, Tony Williams. I think we were expecting something a bit like Cream. They started playing, making torrents of incredibly harsh and complex sound for about 15 minutes, then they stopped, said nothing and started up again. The whole of the City Hall let out a collective ‘What the fuck?’ It was wonderful.

MP: Did you prefer the Beatles to the Stones? Did you find the later Beatles, Lennon lyrics particularly, inspiring?

GN: I could make a playlist of say a dozen Beatles songs that I absolutely love – that would include ‘Tomorrow Never Knows’, ‘I Am the Walrus’, ‘Norwegian Wood’, ‘Come Together’. But I could equally make a playlist that that would make me cover my ears – ‘Michell’, ‘Something’, ‘Lovely Rita’, ‘The Long and Winding Road’.

Whereas the Stones somehow you take or leave as one piece. I take.

MP: Can lyrics inspire novelists? I have heard it said they can.

GN: It sounds perfectly likely though I can’t think of an example in my own case. I’ve had conversations with people who say can you analyse Beefheart lyrics in much the same way as you’d analyse John Ashbery (does he count as an honorary Beat?) and of course you can, but I’m not sure if you’d want to.

I know people who do readings with music and it seems a great idea, and I’ve done it myself a few times but it never quite worked for me.

MP: Has your taste in music changed much over the years? If I knocked on your door now and you were listening to music what would it be?

GN: It’s changed but it feels like a continuum. I can’t think of any music I really used to love and have completely rejected. But I’m not a nostalgic – I like Scott Walker but you won’t find me playing ‘The Sun Ain’t Going to Shine Anymore.’ Tilt, maybe.

The pile of CDs currently next to the player includes Stolen Car by Carl Stone, Jah Wobble’s 30 Herz, Miles Davis’ Big Fun, Congotronics by Konono No 1, John Cage’s In a Landscape, the Acid Mothers Temple with Afrirampo album, the Johny Depp/Helena Bonham Carter soundtrack to Sweeney Todd. Of course most of this music didn’t exist when I was young but if it had, I think I’d have dug it…maybe not Sweeney Todd.

MP: Have you met any star musicians? Heroes? Maybe while you were in LA?

GN: Well one of the things about living in LA which I did for 15 years is that you’re waiting in line in a supermarket and you exchange a couple words with the person in front of you and you suddenly realize it’s Rickie Lee Jones – this happened – though that hardly counted as ‘meeting’.

And I once went to a party that didn’t promise to be very glamorous and I found myself sitting at a table next to Matt Groening. We discussed Captain Beefheart and Henry Kaiser who I still think is one of the great experimental guitarists.

I’m well aware how male-oriented all the above sounds – but the Beats were kind of that way. I read and enjoyed the female Beat poets Anne Waldman and Diane di Prima, and I’ve read some of the accounts by women of hanging around with the Beats, which sounds like very hard work indeed, hence I suppose the title of Joyce Johnson’s book Minor Characters.