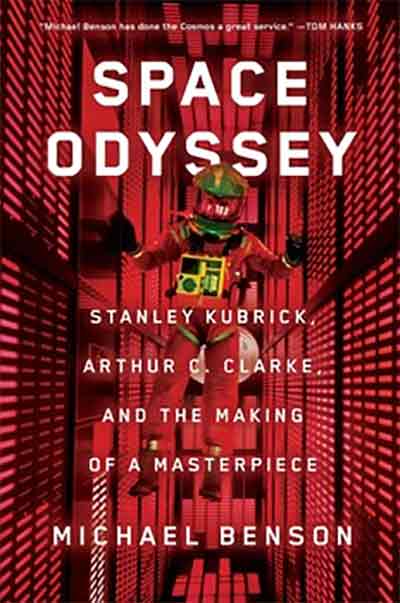

Space Odyssey. Stanley Kubrick, Arthur C. Clarke, and the making of a Masterpiece, Michael Benson (Simon & Schuster)

Apparently the films were released 18 months apart, but in my mind I saw them within a couple of weeks of each other at the same West London cinema. Thunderbirds Are Go was an exciting longer version of Gerry Anderson’s puppet TV show, and if the added length and exploration of Mars wasn’t quite what I expected, and the Cliff Richard & The Shadows puppets sang for too long, I went home a happy boy, clutching my souvenir programme and my mum’s hand. 2001: A Space Odyssey, however, was a different matter. It was epically long, there was little dialogue, and I didn’t understand what was happening, especially in the 20+ minute Stargate sequence. Neither my mum nor I made much sense of it all, why apes were dancing around a black monolith, waving bones, why HAL the computer was killing people, or why after the long psychedelic journey of Dave Bowman he turned into both and old man and an embryo.

The same questions were and still are being asked about Stanley Kubrick’s epic space film. And if Michael Benson’s book doesn’t quite explain everything, it goes a long way towards explaining the thinking behind the writing and making of the film, in readable and detailed chronological chapters. Kubrick was looking to make the first believable and intelligent science fiction film and was recommended the writing of Arthur C Clarke, a science writer and science-fiction author. Although they at times had their differences, and Kubrick – as he did with many people – often bulldozed his way through people to get where and what he wanted, Clarke’s philosophical and scientific reasoning would underpin the many years it took to film 2001.

‘Normal’ films get written, filmed and edited, but 2001 mostly emerged in the studio. Kubrick would set ideological and practical problems to all those working with him: Why would this happen? Was that possible in space? No, it must be filmed that way! No, make it weirder/louder/longer/more believable. New ways of filming were invented by the camera crew and technicians, full size sets took over Borehamwood where most of the film was shot, characters were pushed to the limit, scenes redone over and over, then sometimes abandoned or ignored.

Some ideas took years to resolve. How were the audience going to understand the story without the planned voiceovers? (They didn’t.) What exactly were the black monoliths that appeared in each section of the film? (Some kind of alien signal device.) How were the costume department going to produce believable ape costumes, and how were actors going to breathe let alone act in them? (Enter mime experts who ‘became’ ape.) How was the computer going to be switched off? (Or more exactly, killed… Kubrick makes the computer lose his mind as Bowman pulls his circuit breakers out one by one, from within the mainframe; it’s tear-jerkingly emotional.)

As the budgets went sky high and the film company were on Kubrick’s back even more, having not seen rushes of the film or been given anything to market it with, Clarke retreated back to Ceylon, without Kubrick’s permission or approval for a book deal. It is Kubrick who obsessively assembled and reassembled, edited and re-edited the film for completion. Even at that stage the director was unsure of what music he would use, commissioning and discarding (as well as paying for) a score in the process. He eventually decided to use the likes of Strauss and Ligeti which he had been using as a temporary and makeshift soundtrack.

Eventually it was finished, eventually Clarke was allowed to publish his novel, eventually there were film premieres. Film moguls and businessmen walked out, and the critics panned it. Kubrick cut another 20 minutes from it, and from then on it was a success, riding on the counterculture, youth and the Apollo program for momentum. The book quickly became a bestseller too as 2001 launched into the future, to where we are now.

I was lucky enough to see an original 70mm print in New York a couple of months ago. I’d forgotten how visually stunning the film is, how mysterious, powerful and ‘other’ it remains. Even 40 years later it makes me feel like a confused little boy, it is so awe-inspiring, strange and visionary. Benson’s book reveals the personalities, relationships, details and obsessions behind Kubrick’s masterpiece, but, thankfully, it doesn’t explain or take away anything from the film itself. File under ‘required reading’.

Rupert Loydell