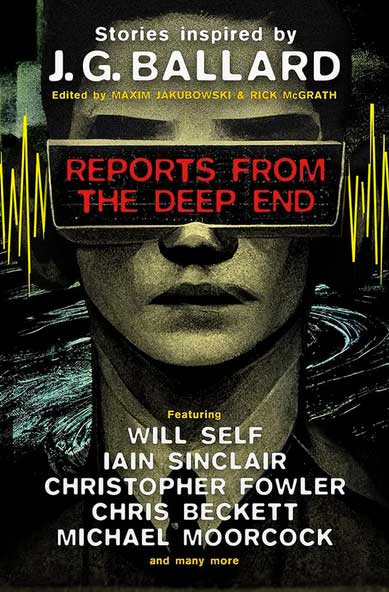

Reports from the Deep End: Stories inspired by J.G. Ballard, Maxim Jakubowski and Rick McGrath (editors), Titan Books

J.G. Ballard himself once said, ‘for a writer, death is always a career move’ and, in their introduction to this collection, the editors point out how, though a writer’s influence often quickly wanes after their death, in Ballard’s case, ‘his work and ideas are still strongly reflected in the stories and novels of countless contemporary authors.’ They go on to talk about what is meant by the commonly-used adjective ‘Ballardian’ and quote the Collins English Dictionary definition: ‘resembling or suggestive of the conditions described in J.G. Ballard’s novels and stories, especially dystopian modernity, bleak man-made landscapes and the psychological effects of technology, social or environmental developments’. Accurate though this is, there is a lot more to Ballard than the specifics mentioned here. If we want to see the bigger picture, it might help to spend a few moments looking at which writers influenced him. In a 1992 essay, The Pleasure of Reading, he talked about the things he’d read over the course of his life. As a child in Shanghai he read Alice in Wonderland and Robinson Crusoe. His list of ten favourite books includes Hemingway, Coleridge (The Rime of the Ancient Mariner) and William Burroughs. He name-checks Conrad, Graham Greene and The Water Babies. Echoes of his own reading crop up throughout his work. For example, reading Ballard’s novel, The Crystal World, with its colonialist overtones and its journey upriver, it’s hard not to think of Conrad. Reading his short story, ‘Terminal Beach’, it’s hard not to think of Robinson Crusoe. (The Water Babies, incidentally, also loomed large in the life of M John Harrison, an author conspicuous by his absence from this collection).

As well as the wide range of influences that helped shape his writing, one needs to think, too, of the effect he had on late twentieth-century science fiction. Along with Michael Moorcock (who does get a look-in here) and Brian Aldiss, he was a key player in the emergence of New Wave SF, turning his back on space opera and ‘outer space’, preferring instead to explore ‘inner space’. In doing so, he played a major role in blurring the distinction between SF and literary fiction. If there’s one thing that distinguishes most of the best stories in this collection, it’s that they’re at least as much concerned with the question of ‘inner space’ as they are with all the urban dystopia stuff.

Writing a homage is a dangerous game: if you do, you invite comparison with your subject and, if they were one of the best, you’ll probably be found wanting. For example, reading some of the stories in this collection made me realise how Ballard was a master of presenting complex situations with seemingly effortless clarity: rarely, if ever, do you find yourself going back a few pages to figure out what he’s going on about. And he’s never clunky. If you’re writing a homage, clunk at your peril. And know the author you’re paying homage to: one or two of the stories in this collection I liked least seemed to me to have only a tenuous connection with his work. One reminded me more of Quatermass, or perhaps John Wyndham. Part of the problem is inherent in the title of the book. This is not, as I thought at first glance, an overview of the influence of J.G. Ballard on the short story since his death. That would be quite an anthology. What we have here are a collection of writers’ responses to a call for ‘stories inspired by J.G. Ballard.’ The result is that one or two of the stories come over as no more than humorous pastiches one finds hard to imagine finding a life outside the book.

On the other hand, quite a lot of them are really good and there are more than enough of these to make the book worthwhile. The first story in the book (I can see why the editors put it first) is a case in point. In Geoff Noon’s ‘Chronocrash’ the science doesn’t even pretend to be remotely possible. The idea of driving car-like vehicles down roads through time is pure Surrealism. It’s the stuff of dreams, more Weird than SF perhaps. The way Noon uses it to create a satire of modern academe is very funny, too. The narrator goes off in pursuit of a colourful charismatic time travelling character, Alexa Brandt. The visual verbal similarity of the names immediately put me in mind of Amelia Erhardt. I suspect this is deliberate: two female pioneers, one of the air, the other, time. There is also a suggestion of the enigmatic woman in Ballard’s ‘The Prisoner of the Coral Deep’, another story dealing with time-fluidity. The narrator pursues Brandt both temporally and romantically. Surprise, surprise (given the title), she’s forever crashing her car/time-machine which, we’re told, is an Estelle Vanguard. When the narrator parks next to it in the car park, he’s concerned that he’s accidentally chipped her paintwork on opening his car door, only to discover her vehicle is covered in chips and dents. One can only go so far backwards or forwards in time: places in the past are sharply defined, but the people who inhabit them move more quickly and so are seen only as fleeting, ghostly apparitions. There are touching accounts of ghostly encounters with these people from the past. The future is very different and one can be subsumed into it much as one can into Ballard’s crystal forest. Perhaps it’s just me, but Ballard’s writing often gives me the feeling that the main character is, in the fictional present they inhabit, always living on the edge, on the verge of some great revelation. Whether it’s just me or not, Noon captures this: Alexa Brandt ‘was my age or thereabouts, but I couldn’t help feeling that she possessed arcane knowledge of some kind, perhaps of the nation’s impending doom. Ridiculous, of course: we could travel a few days into the future, no more.’ It’s one hell of a story and I wish I’d written it. It works on so many levels.

Perhaps my favourite story of all, though, is ‘Art App’, by Chris Beckett. A billionaire entrepreneur, Wayland Price, pours millions into creating a new form of art, in which AI and elaborate engineering are used to enlarge the 2D, framed Surrealist artworks of Max Ernst, Paul Delvaux and Salvador Dali into 3D worlds that extend beyond the limits of their frames and which the viewer can explore through virtual reality. Not only was Ballard known for using Surrealist art-works as starting-points, but also the story pretty clearly draws on something Ballard actually said about his life. He had a copy of a Delvaux in his Shepperton writing room. The huge painting stood on the floor beside his desk. He said of it, ‘I never stop looking at this painting and its mysterious and beautiful women. Sometimes I think I have gone to live inside it and each morning I emerge refreshed.’

David Gordon’s ‘Selflessness’ is another intriguing exploration of inner space: an unemployed man is seduced into taking part in a medical experiment for money. He’s given a pill that breaks down the mental barrier between himself and others. He gets enough to pay the rent out of it but he’s being exploited. Talking of inner space, Adrian Kinty’s ‘A Landing On the Moon’ has a bold – and effective – simplicity about it. Will Self’s contribution, ‘Operations’, is a surreal encyclopedia of bizarre medical procedures. It bristles with Self’s dry, wry wit and, in true Ballardian fashion, pushes beyond boundaries more squeamish writers would baulk at. Iain Sinclair’s ‘London Spirit’ is part essay, part derivé, part memoir and part short story. Sinclair’s narrator encounters the ghost of Graham Greene in a bookshop he once helped to run. Greene peruses the shelf where his own first novel, The Man Within, sits. Concrete Island sits on the shelves not far from the Greene book and the narrator wonders if he can summon Ballard’s ghost. He imagines a car crash in the book happening on ‘a tease of liminal ground’ between the Westway, the M41 and the A40. After a digression taking in the author and film-maker Chris Petit (who made a film with Ballard) and Patrick Keiller’s film, London, the narrator sets off on a psychogeographical derivé through the landscape of Concrete Island, hoping to somehow invoke the ghost of J.G. Ballard.

Michael Moorcock’s contribution to the book is a new Jerry Cornelius story. It’s difficult to say exactly when and where it’s set (‘The New Alchemy threatened. The boundaries between physics and metaphysics were blurring again. Voila! Le Multiverse! Behold the Second Ether!’). It features the familiar cast: Miss Brunner, Catherine Cornelius, Bishop Beesley, et al. The Derry and Toms rooftop garden (familiar to Jerry Cornelius fans) gets a J.G. Ballard makeover: ‘clouds of yellow flamingoes would burst into the air from the ornamental waterway and settle on surrounding branches or chimneys. Then, slowly, one by one, they would drift back. To her north she could see the last ruined high-rise, stabbing from the water, an island of burned-out concrete…’

David Quantick’s Champagne Nights is set in a labyrinthine gated community overlooking the Bay of Cannes: a J.G. Ballard setting if ever there was one. At the behest of one Machliss (‘clearly some kind of headshrinker’) the narrator goes off in search of four missing residents. It has the feel of a dream within a dream. The final story in the book, ‘The Next Five Minutes’ by James Grady, is a surreal, darkly comic story in which a simple – if gruesome – life-hack penetrates the highest level of US security. There is stuff in there one finds hard to get out of one’s head once one’s read it, but to say more would be a spoiler.

It would, as I’ve already said, be interesting to see an anthology of stories by writers influenced by Ballard, but not, like these, consciously written for an anthology of work inspired by him. However, I’m suggesting this would be good as well as, not instead of, this book. This one should both intrigue and entertain J.G. Ballard fans and, indeed, should be of interest to anyone curious as to the direction being taken by literature these days. Those who read it will never look at a jar of olives in quite the same way again. As to what I mean by that, you’ll have to read it yourself to find out.

Dominic Rivron

.