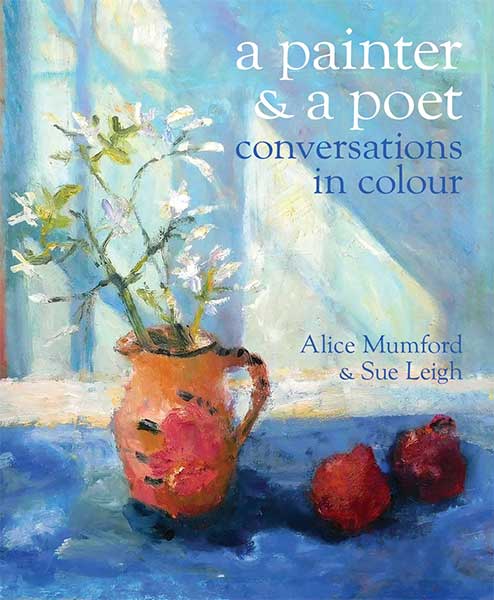

a painter & a poet. conversations in colour, Alice Mumford & Sue Leigh (Sansom & Co)

Alice Mumford’s paintings, mostly still lives, but often with windows or open doors leading out to the landscape, are exquisite, glowing exercises in form, colour and perception. The obvious comparison for me is Bonnard, with some underpinning from Cezanne and Matisse. This is meant as high praise by the way, not as an implication of copying or pastiche; Mumford has her own way of subtly delineating the forms of table and chairs, jugs, flowers, bowls and fruit, and of making colour sing. The air around her subjects is saturated in colour, heavy and hazy with the effects of light, distinct from the patterns of tablecloths, shadows and wallpaper.

Sue Leigh is a new poet to me. Here, she mentions how she came across Mumford’s work and requested permission to use a painting for a book cover, and how later on they met and became friends. This book is the result of a decision to formalise and make public some of the discussions they have had around writing and painting, similarities and difference, process and context. Quite rightly, Leigh points out in her ‘introduction’ that ‘[c]ollaboration does not seem quite the right word, noting that they ‘would be working alongside each other rather than with each other.’ The interaction, responses to each other’s work, continued after the specific period at Mumford’s house in Cornwall, and became this book, which is also a catalogue accompanying an exhibition in a St Ives gallery.

The specific pages of ‘conversations’ starts by discussing how poems and pictures begin. I like the fact that neither poet nor artist mention inspiration, instead they talk in terms of preparation and rituals, thinking and organising and then a constant editing of both paint and language. Although Leigh talks about ‘paying attention’ and ‘intense listening’, she unfortunately still mystifies the process, declaring that she ‘cannot say where poems come from’, which to me is a denial of both authorial responsibility and of language: poems (on the page) are quite clearly constructed with words, just as paintings are made with paint.

Mumford picks up on Leigh’s mention of ‘the physical experience of writing’ which is interesting, the fact that (in Mumford’s words) ‘[w]e hold so many things in our body’. She talks of physically limbering up and getting ‘the body to remember’, but also of painting being a ‘conversation – with myself, with my mother, a close confidante, the past, dead artists’. This, it seems, is at odds with Leigh who states she doesn’t think she ‘is aware of anyone else when I write’, a feeling I can certainly empathise with.

Even better for my understanding of creativity is Mumford’s declaration that:

[w]e need to allow the chaos, not to overwork or attempt to pin things down. There

should be imaginative space for the viewer. So the viewer becomes a participant.

[…] I think that things that are just out of reach are more comprehensible.’

For me, this describes writing as much as painting; this is how poetry works, by metaphor, allusion, hint and spaces for ideas and the unspoken. Also, Leigh’s comments further on, that so much shaping of a poetry collection is ‘intuitive as you work and it is only later that you see the connections.’ That is the author becomes reader and intepreter as they start to understand what they have made.

Honesty compels me to say that most of the poetry in this collection adds little to the reproductions of the paintings. All too often, they try and make specific what is left open in the images, or the reductive banality of ‘jasmine and blue haiku’:

white petals fallen

on a blue cloth have made

a paisley pattern

which anyone who has paid attention to the painting has already seen. And whilst I do like straightforward language, I also expect new ways of describing things: surely Bonnard deserves more than ‘lemony-yellow’?

Criticisms aside this is an interesting collaborative project and publication. The actual documented conversation between painter and poet is especially intriguing, and I’d like to see that developed more, and more in-depth discussion of ekphrasis, the visual elements of poems, texture; how poems move beyond narrative and description in the same way that Mumford’s wonderful paintings are so much more than just pictures of things.

.

Rupert Loydell

.