Dear Celeste,

This morning, in the twilight of a heavy dawn shower, I tried to edit some of the mouldering boxes in the library. What a grand name for a cube of walls with rising damp! Drawn away from the thrashing branches and lancing rain, I heard sounds from the past – an overlapping duet of blackbirds, you children playing, the smell of honeysuckle. Four hundred miles away and four hundred years. Looking around in the room’s silence and then beyond the window, there was no reassurance in today’s flowers. In the garden outside the rain died away, but neither the low stone wall towards the falling woods, nor even the sunlit fells, rising behind, meant anything to me. Their reality faded. Their bright screen was only one of those faked scenes in films where you know they’ve paid the fire brigade to contradict meteorology.

The last thing I would ever wish to do is depress you, but to find all those old things you made – no longer chronological, unexpected, a miscellany – tears me out of daily life . . . and that is good, he says. Anything that breaks routine in such a way is good, he claims – against the disquieting rage inside: closing his eyes against himself; forcing a smile.

The stories you made, the books you drew, the magic paper screens . . .

I reeled through “Mum’s baking day”; turning the wooden dowels that have pierced that inside-out decorated box for two hundred years. It made me laugh and perhaps began to induce the timeless state about which I’ll always bore anyone who’ll listen. Amazing how the cheap felt pens have not faded, not one jot.

Did I ever mention that dream I had about a middle-aged man who can come and go, disappearing in one life to appear in another? Each time though, he could always take the best of his life with him, so long as he could hold it tight enough. This must have been influenced by a dream I had when I was a kid, one when I knew I was dreaming. I had this special packet of sweets and was convinced I could bring them back to waking life. Later my mum explained the deep red marks on my palms, showing how they fitted with a tight fist’s fingernails – which seems obvious now.

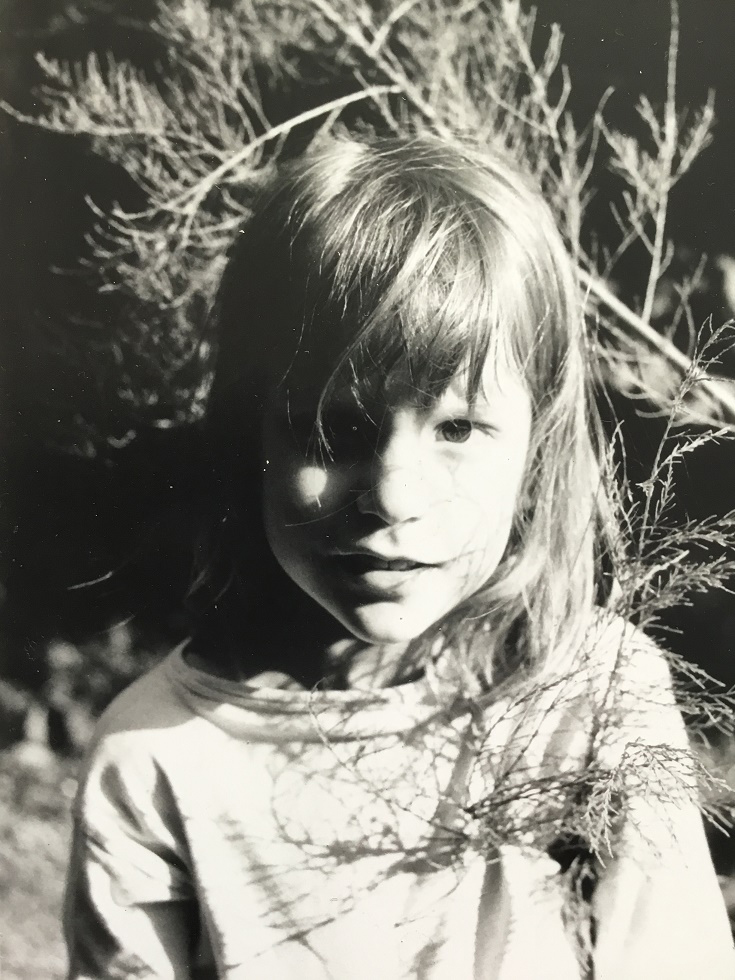

In one of your homemade books about a holiday, I came across a photo of you with your brother, one I feel sure I’ve never seen before, both so young and shining . . . and the doors of time began to slam shut all down the corridor behind me.

____________________________________

Every day that I wake up, I lie a moment wanting some kind of peace, some satisfaction, some earthly idealistic hope. Inevitably, inaction rules out such things. Each day is severed from all that went before – unless I make the effort to rejoin it, unless the forgetting of motion seems to rejoin it. Life in time is a chain of fragments and most of us only cope by forgetting, a big forgetting – the huge forgetting outside the brackets. But this forgetting does not seem to be an option for those with what . . . with too much awareness? Is that what it is, this over-sensitivity, this neurosis, this inability to forget? I always hope that sheer bloody-minded willpower might serve instead.

Amongst the letters, the birthday cards, the humorous certificates, I know that the photos I find of you, must be the people you were; and I know that these other things – these partly random survivors – were what you made, or saw, or did. I know again when you learnt to swim and when we went to stay in Wales, or crossed the Channel to France – I can feel the boom of the ferry engines and see the churning wake under the sun deck. I know that none of these was even a hundred years ago. You would know all this too if you were here. If you were here, you’d laugh and remember some of the things, feel them and know them inside.

Looking for a moment the other way, there’s one other who especially I remember; who appreciated our young family at the time, valued it more than I could. Her whose writing crosses sheaves and postcards waiting in the boxes – writing that now looks almost runic, mythological. Your grandmother too, would laugh and remember all this. And whenever all the doors are open and time disappears, I’m sure she still does.

Back into the box in different random layers go the living, dying, proofs, and fifteen years becomes fifty. But the pragmatic impulse that might have soured this recovery of lost treasure, has failed. The protective boxes are no emptier.

Which is truer, our bursts of reckless pragmatism, or the heart’s self-destruction? We must move on, but at what cost and where are we going? The human condition is not tenable. Almost nothing in it makes any sense. As I’ve wittered on before – the destruction of past caring, all those lives vanished . . . people that had we known them well, we’d have to struggle to forget. Yet isn’t all memory and art concerned with just the opposite? With remembering and identification? Isn’t that the only true point of it all – resurrection or intense identification with some other moment or time or person?

Also in the box, I found some strange belt of power, a gold and silver-foil bejewelled medallion on a red band, and under it an old poem of your brother’s. A summer poem from 17 summers ago – in which trees cover themselves with leaves and bees look for nectar.

The lines combining ringing church bells with picnics on the beach had a strange effect – conjuring a time before he or you were born: A church where the girl who became your mother, climbed the tower with me. Together, from the roof, we saw the map of lanes that had led us there, and curving in to meet their end, under red sandstone cliffs, the beach. As the bells began to ring beneath our feet, we saw the endless blue optimism of the sea. And that was like yesterday!

The poem’s next lines were light: of crabs and sandcastles and kids covered in “sun cream and ice cream” – that was your brother’s great joke . . . before he travels inland and becomes omniscient: “Mossy walls, wasps, cherries start coming . . .”

It ends with memorial grandeur, under a Tor – another picnic – the primeval above the fleeting: “Rocky moors stand high in the sun”.

With cameras now, the click of a shutter can be a chosen sound effect, and the moments reeled off without crucial decision. That is quite different from the photos in our albums – and even from the odd failed image seamed in the boxes. We had to select and take a risk and pay for our mistakes.

If the human condition is untenable, why do most of us keep going? Is it through hope – or only through guilt, only ultimately through fear? Life has its moments, and so many objects in the box brought others back. I know I’ve been lucky. My life has had chains of perfect moments – far more than most. But don’t we all crave more than moments? Don’t we all desire the belt of power that will take us away from ordinary life? For the best of us is hidden inside, and shuns the daily round in which, even together, we’re largely condemned to exist alone.

Some moments have a sense of eternity within them, a timelessness that expands us – moments from life or art, or perhaps most purely, from dreams, where our trained rationality and the tyranny of facts don’t interrupt and contradict: Dreams of love; dreams of flying; dreams outside this body. Dreams when I escape my claustrophobia. Ironically, it’s anxiety and technology, that progressively keep us under control, and envy under materialism is part of this unintentional conspiracy.

Trying to hold the line between sincerity and sentiment, between onward force and self-pity, am I managing to say anything here? Do I celebrate, or does everything sound only negative or maudlin? All these uncontainable feelings! For what I’m about and unable to say, is just the tip of a hidden unconscious mountain. A reservoir of things we did together or have told each other – but now can’t clearly remember. All those photos, the shaky films, the letters and diaries we’ll never have time to see or read . . . And if we did, your newer life, my fractured waking every morning, would be consumed by the past – or by the myth of the past. Time would run backward. But where too? Would it recover lost treasure or only a stress of claustrophobia, an isolation, a stagnation?

Without recollection and reassertion, nothing lives. That yea-seeming directive – we’ve laughed at versions of it declaiming from stickers in cars – to Live in the Moment, is glib: The moment that was then, has to be now too. There is no moment except as kept alive by its hope and its echo. It doesn’t exist without the long-term memory of it. But how do we forge a positive connection between us now and us then? Is it mostly preserved by what we don’t or cannot say? Happy or irritated to be with each other – in our now, less shared, experience of time – how can we combine all the fragmented selves, and disregard the generational divide?

These questions: how to keep the vital spark of connection; the passing of time; all the people we were that we can never be again . . . are challengingly depressing I know. I’ve always been sure though (if of little else), that it’s through the time-filled that we will find the timeless. But can I always keep believing that? Writing to you, my daughter, who I love more than anything can say, yet cannot express . . . have I protested against time too much? Am I persuading myself here again? Is that how I always repair myself? Patch myself up every day, using so-called art or at least creativity, a self-indulgence, a therapy. Making memorials to force the moments to exist and keep existing, all just to be able to carry on.

That day we forded the wide but shallow-seeming river, whose unexpected force shone fiercely in the sun, and suddenly realised we needed to grip and trust each other’s arm . . . that day which in fact was only a few weeks back . . . yet as I sink, it feels like it belongs in the box, a hundred years past.

How impressed my mother used to be by the model railways I built when I was nine or ten, the tunnels, the lanes, the landscape around them. As if it was the act of a God – to build a world! This came back a few weeks past in another dream – if three dreams in one letter isn’t too many? But in this dream, it was the real world we looked down upon – a wide panorama featuring four main lines passing happily through a perfectly mown cutting. On these tracks a continuous cavalcade of trains was passing, steam expresses, or diesel and electric; cheerful freights – a fabulous Jubilee of loads and colours and eras . . . and we just beamed upon the view, standing by then much closer to the joyous scene, behind the old wooden fence at the lineside . . .

My parent’s house: the easy rooms, the furniture, the high garden above the park with the lawn shaped like a wine glass, the towering sycamore tree silhouetted at night against a sea of lights – when I used to go home for visits, in summer or winter my parent’s house always felt like a place that was fixed forever . . .

Anyway, I’d better go. The fire needs more coal and the sky looks threatening – I chanced a load of washing to the gaps in the raking clouds . . .

Got some replacement reading glasses from Poundland (or it might have been Pound World?) the other day. Can’t imagine how they look and I don’t want to! (though its more myself I don’t want to see anymore. Not that I was ever that vain, I hope?)

Lots of Love, Dad XXXX

Lawrence Freiesleben