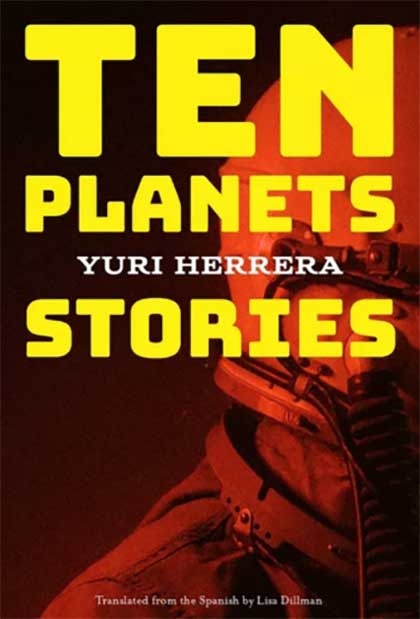

Ten Planets, Yuri Herrera, tr. Lisa Dillman (108pp, £11.99, And Other Stories)

Change one thing and think about the effects of that, and you have a new world. In Ray Bradbury’s Fahrenheit 451 the firemen burn things, and books are subversive; the author took the idea from watching a newsreel of the Nazis burning ‘degenerate’ literature. Yuri Herrera plays with similar causes and effects, sometimes within the language itself, more often as a by-product of the worlds he creates.

So in ‘House Taken Over’, the characters are called things like &°°°, *~, #~ and @°°°. To be honest, it’s bloody annoying, and detracts from the story itself, which is about a house that learns from its residents, although it’s unclear if this is to cater for them or to imprison them. More interesting are texts like ‘The Science of Extinction’, where a man forgets not only his past but also the names of things, as he watches ‘[t]he increasingly depopulated world rewilding on the other side of the glass’ and listens to ‘[t]he too many silences’. It’s not clear if this is some kind of post-apocalyptic world or one vacated by his species: when he is visited by what he perceives as ‘an undulation of swirling sounds, colors, velocities’ he reports that he ‘found a message that someone left us on a card. It says, “Everyone is going away.”‘

Other stories are built around very different ideas: Zorg invents ‘stories about improbable worlds’; in ‘The Other Theory’ it is ‘confirmed that Earth is indeed flat’, resulting in the formation of a sect with strange ideas about ‘Earth as a host wafer, a tortilla, a cracker travelling through the universe, just waiting for an encounter with the mouth of the Creator’; whilst in ‘Living Muscle’ we find out about ‘a planet made of living muscle’ which travels across the universe either humming or in silence, and that it has not been named and will not be investigated further. Others are more straightforward, stories like ‘The Last Ones’ sets itself up immediately – ‘Before becoming the first human to cross the Atlantic on foot’, whilst ‘Warning’ is a brief spoof of online agreements, perhaps with a nod to Ayn Rand and her fascistic ‘free market’ and individualistic economic and political manifestos, in its use of ‘The Rand Corporation’.

My main problem is that the more interesting concepts often result in the shortest works, whilst some thinner ideas are drawn out, to little narrative or literary effect. Some of this is clearly to do with translation, as Lisa Dillman highlights in her ‘Translator’s Note’, where she notes problems with ‘standard versus non-standard usage’ of words, the way that Mexican Spanish words have multiple meanings, and that Herrera’s syntax is often very different from the English translation. In the end, however, Dillman relies on the fact that Herrera’s ‘belief that meaning is never fixed, and readers will make their own interpretations’, which, of course, the reader always does.

The back cover blurb on my proof copy suggests that the stories in Ten Planets draw on both Borges and Calvino, as well as science fiction and noir, but it’s hard to see the work in relationship to either of those authors beyond the occasional intertextual nod (Herrera’s ‘Zorg , Author of Quixote’ and Borges’ ‘Pierre Menard, Author of the Quixote‘) and the fact that so many of the stories included here are incredibly short, just as Borges’ work often is, using a story to explain an idea rather than tell a story. It’s clever stuff but to be honest a bit boring, and it mostly feels like an author deciding to experiment and ‘subvert’ science fiction, not understanding that literary fiction and science fiction have moved on since they last read or engaged with the genre

Rupert Loydell