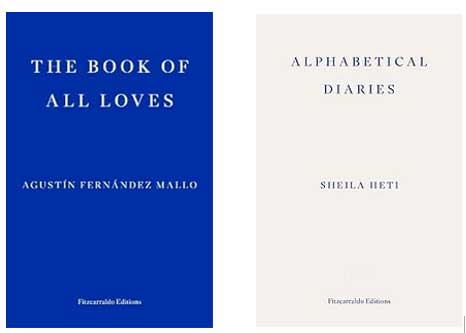

The Book of All Loves, Agustín Fernández Mallo (Fitzcarraldo Editions)

Alphabetical Diaries, Sheila Heti (Fitzcarraldo Editions)

Agustín Fernández Mallo is the author of the amazing Nocilla Trilogy, and one of a wave of new experimental Spanish writers. The Book of All Loves is, as you can imagine, a kind of love story, but it is also a dystopian novel, a work of philosophy, and a bit of a mindfuck (in the best possible way).

There appear to be three stories going on here: a dialogue between ‘she’ and ‘he’ about love in somewhat heightened, sometimes sexual or occasionally pretentious terms; strange musings by a narrator, who draws the reader’s attention to different types of love, often rooted in cultural or scientific terms; and an account in the past tense of a couple in Venice.

The she/he dialogue is set after The Great Blackout, which appears to be related to an expanding area of sensory deprivation that occurs in St. Marks Square in the Venice story. She/he are, or assume they are, the last two people left, hidden away in a beautiful valley, besotted by each other, romantically and physically:

When your body and mine light up in the night like

fireflies, the moon darkens. More and more with every

passing day.

– he says.

The sun already did the same. As did artificial light, even

earlier on – it gave up on the world of the living with no

explanation.

– she says.

Each time a fragment of conversation such as this occurs, which is often, we then get a discussion of love in a different form. After the extract above it is Language love, but there are numerous others: Urban love, Advert love, Immemorial love, Epidermal love, Oxide love, Underlined love, Last judgement love, Fire love, Match love, Mandible love, Crystallized love, and many, many others.

In each of the four sections of the book, the she/he dialogue and the loves then cease and we get a fairly straightforward account of a romantic holiday in Venice. The former do not change, but gradually the Venice story allows us to bring the seemingly disparate strands together, towards a moment where urban landscape becomes nature and the two lovers become ‘two enigmas of flesh’ caught up in eternal conversation, part of which we have ben fortunate enough to be privy to.

It is a disturbing, engrossing read. The only comparison I can think of is David Markson’s Wittgenstein’s Mistress, where a woman wanders New York and then a beach, convinced she is the only remaining human, trying to work her life story out. But Mallo’s book is very different and totally original. I suppose it could be a metaphor for how obsessive love shuts the world out and creates a new insular world for a couple, but I prefer to read it as a kind of fantasy novel, where humans become post-human, something new and very wonderful; where love conquers all.

Sheila Heti’s Alphabetical Diaries is very different. It is a diary, ten years of the author’s ‘thoughts’, rearranged alphabetically, taken apart and reassembled as dense blocks of prose: relentless, often staccato phrases with little space around them in 25 alphabetical chapters. (There is no X.)

I’d previously read a 17 page online piece by Heti which was published as ‘From My Diaries (2006-10) in Alphabetical Order’, so was expecting a longer version of the same, but the work appears to be partly different material, and has a very different texture to it. The online piece looks like and reads as a list poem, with a lot of headings – single words or short phrases – within the text. It also undercuts itself with its jokey final line: ‘What a load of rubbish all this writing is’. Although that phrase is present in the Fitzcarraldo book, it is no longer the final phrase (and I won’t spoil the read by telling you what is).

You would think that this might simply produce a pile-up, even a car-crash, of language; but you’d be wrong. What it allows the reader to do is focus on the language and experience how each successive phrase reconfigures what has gone before and raises expectations for what comes next. And if you are the kind of person who worries about things like ‘the author’s voice’, I can assure you that Heti’s voice is more than present, because of the vocabulary, syntax and her subjects; it remains her writing. By rearranging sentences alphabetically we notice textures of, and the changes in, her voice, as – for example – ‘I was’ slips to ‘I watched’ to ‘I welled up’ to ‘I went back’ and then ‘I went back’, ‘I went into’, ‘I went to’, ‘I went up’ and so on.

By fragmenting and then formulaically rearranging these personal records, Heti has reinvigorated them as more than a journal, brought them to life as a fascinating book which highlights the consistency and inconsistencies of us all, how our minds flit from subject to subject to elsewhere. It is a warm-hearted, individual, exploration of what it is to be alive, what it is to be human. As the opening line says, it is ‘A book about how difficult it is to change, why we don’t want to, and what is going on in our brain.’

Rupert Loydell