Dark Room, Garry Fabian Miller (Bodleian)

Adore, Garry Fabian Miller (Arnolfini)

Last Evenings, Garry Fabian Miller, Oliver Coates & Alice Oswald (Filtow/The Letter Press)

Against Leaves, Alice Oswald & Garry Fabian Miller (The Letter Press)

for measuring blueness, Alice Oswald & Garry Fabian Miller (The Letter Press)

When I first got to know Garry Fabian Miller and his photographs, he was working with plant material, making direct images from the likes of leaves and seed pods, sometimes in grids, documenting individuality, contrasts, change and the passing of time. This had been preceded by a series of photographs of Sea Horizons, which have since been written into histories of land art with the entire series exhibited and recontextualised.

This recontextualisation is not unusual. Miller originally discussed his art in terms of science and optics, but soon moved towards a spirituality, curating The Journey exhibition and conference in Lincoln, which engaged with ideas of site-specific art, pilgrimage, contemplation, and community (and because of some of those present health care and well-being). Sister Wendy Beckett was a speaker there, a charismatic one, although in the calm light of day her tendency to see (her) God in everything, a result of her prioritising interpretation over the image itself, was not a rational basis for art criticism.

There were vague, if somewhat naive, discussions about somehow using the Church of England’s parish system as a basis for art, which came to nought (I don’t think Miller had realised the difference between the Quakers and the establishment C of E!), and a kerfuffle about a nude male statue in Lincoln Cathedral, but the weekend conference helped cement the relationship between Sister Wendy and Miller. One of the results of this was the book Honesty, which my press Stride published, containing five short texts by Sister Wendy and a sequence of images of the eponymous seed pods. When we designed it, Miller talked about it being a kind of prayer book.

I moved away from Devon during a time when MIller was having to rethink and change his practice, partly due to the fact that Cibachrome photographic paper was not going to be produced any more, but also because the ‘symbiosis between photography and photosynthesis’ had run its course. Miller gradually came to a realisation that he could work with light and colour itself in his darkroom, rather than with any kind of filter such as plant material, or the likes of the grids or cross shapes produced by the vertical and horizontal window frames which he had photographed during a residency at Petworth House. In Adore, Miller states that ‘Their crossings makes the centre of my world’, relating it to the idea of home, which is ‘The heart of the real, beyond which all becomes fragmented and falls apart.’ He also goes on to state that ‘This is not a symbol of doctrine, but the mark of a free spirit.’

In Dark Room, which is a beautiful hardback publication serving as both monograph and autobiography, Miller states that he ‘wanted to do more with less’ and that he ‘was beginning to recognise limitless potential between time and exposure as the activator of pure colour.’ We are still in the realm of science here, if somewhat romantically described, but elsewhere we get more mystical statements, such as

The image is only waiting for the chemistry. As soon as it receives

the light it makes itself. If you stay in the back of the darkroom for a

photographic exposure of, let’s say, six hours, the experience

becomes a kind of meditation – a rite.

or the likes of

Some days in the darkroom it feels as if an image is waiting

on the outer margins of visibility […]

I’m not very good at this kind of talk, which also features in the smaller and also beautifully designed book Adore, published to accompany a major exhibition at Bristol’s Arnolfini Gallery. Statements of this type sidestep authorial and artistic responsibility, and befuddles what is actually going on, which is that Miller has constructed an image and chosen to make it. And, yes, sitting in a dark room for hours on end, whether photography is involved or not, can become a kind of meditation, but what has that got to do with the mechanics of photography or the images that result?

Miller has always lived a simple, ordered and organised life, spending time gardening, walking and reading as well as making art. His beautiful house on Dartmoor is a light-filled sanctuary and Miller has always taken time to think through and plan what he has done, wants to do next and how he will facilitate that. His studio contains not only a darkroom but a white space for looking at and considering the work he has produced.

Sometimes, however, it seems that this becomes overthinking. The Sea Horizons series do not strike me as particularly original or interesting. Many artists – myself included, not to mention Sean Scully and others – take these kind of photos as reference material, mostly regarding them as stripes of colour. I am not sure they relate to land art practices (Richard Long’s photos, for instance, are only to document his art , are not the art itself); they are certainly not as innovative as work such as Hiroshi Sugimoto’s night sea photographs.

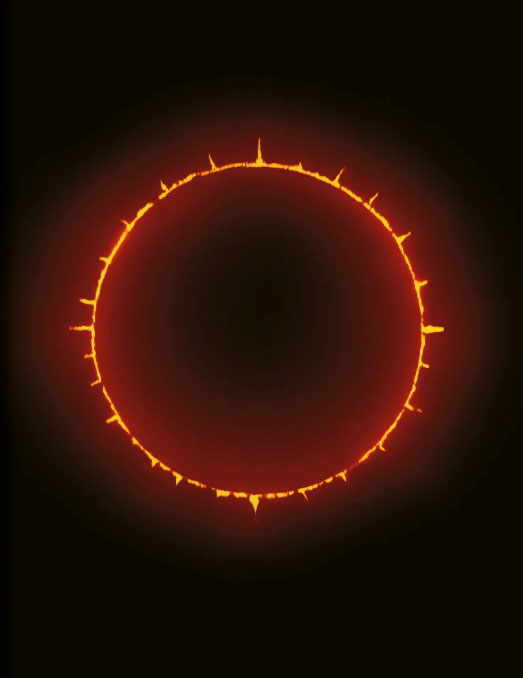

In a similar way, many of Miller’s colour abstracts of the last few years seem simplistic, relying mostly on their large scale and surface sheen to bewitch and bedazzle the viewer. I have no problem with abstraction, but apart from the fact these aren’t paintings they seem to be exploring similar territory to, for example, early John Hoyland stained and poured paintings, some of the less complex works by Helen Frankenthaler, and Kenneth Noland’s geometric works. Or perhaps they could be considered as less sculptural images than James Turrell’s light works. For me the absence of human traces in Miller’s photographs is a problem: despite their vivid colours they are cold and lifeless.

All artists at times pause and wonder how the world around them is so much more complex, beautiful, colourful and interesting than their own work, but all too often with MIller’s later art I can’t help but consider then in relation to images from space – solar flares, or Hubble telescope images – and feel that Miller’s work is too simple. Or perhaps I have simply lost my sense of wonder, something which Miller has in abundance, about the world around him, but also about colour and technical possibilities. The floating red square which floats against pink, ‘The Blossom Room’, is hard to reconcile with the statement Miller places opposite:

The pink blossom

is now here,

its beauty to be seen

or imagined.

The photo neither depicts or evokes the complex colours and movement of blossom; there is little to look at or actually see.

Miller is now exploring the use of natural dyes, which has also led him towards collaborations with textile artists and rugmakers. The resulting hangings simply do not have the luminosity of Miller’s photographs, and I am not convinced that reframing images through craft techniques is the right way to go. Instead, the works seem part of Miller’s wish to leave a legacy, to reframe and recontextualise his work, to turn it into a series of narratives about landscape, the self, a vague mystical spirituality (be that Christianity, Don Cupitt’s ‘Solar Theology’ or simply ‘light’ and inspiration) and a narrative of one artist reconsidering his art and practice as he carefully used up his remaining stock of a photographic paper which is no longer produced. The Adore publication is very similar to Dark Room in this respect, and although it brings some different contextual material and concepts into focus, both books take a similar approach and repeat many images and ideas.

Miller is articulate and engaging: his lectures for the Bodleian Library have been intriguing and informed as he tells the story of his life and art, but – and he is not alone in this – he less and less discusses the formal properties of his art works, instead surrounding it with allusions, quotations and collaborations, which sometimes distract and undercut as much as contextualise, inform or complement.

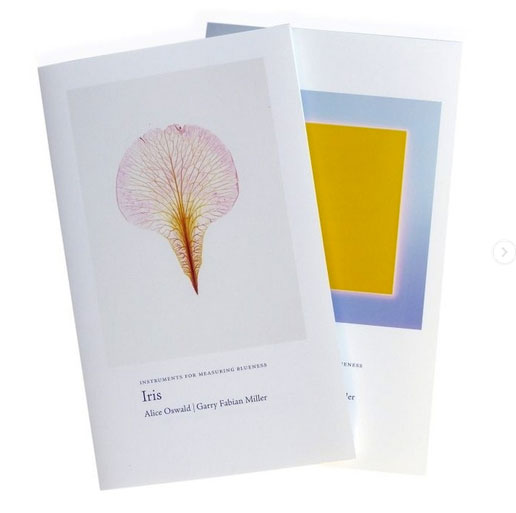

Having said that, the three Letter Press pamphlets are beautifully designed publications, which include poems by Alice Oswald rather than Miller’s own writing, along with carefully reproduced photographic images, including – in Last Evenings – stills from a film by Miller, which includes music by Oliver Coates. Book jackets unfold to become posters, text fades in and out, colours sing, cards unfold into concertinas. I confess I prefer the work presented this way: short poetry, small selections of images, a size I can engage with without feeling bullied or persuaded by the overwhelming scale of many of the originals.

Apart from the images of Honesty, my favourite Miller photograph remains ‘With Its Own Light’, a leaf turned into a flame, a reproduction of which prefaces Dark Room. It, or a very similar image, was placed in one of Lincoln Cathedral’s chapels during The Journey, and its small intensity, its focused colour, lit up the space. For the moment, Miller’s current work does not have this effect on me: I am rebuffed rather than seduced, and Miller’s suggestion that he is an ‘unlikely carrier’ of ‘the residue of English Romanticism’ does not help, any more than the claim that ‘photography is a direct extension of the human imagination’, or that it ‘allows the projection of an inner vision – a mirror of thought and dreams’. For me this falls into the trap Surrealism, mysticism and new age beliefs fall into: thinking that the ‘inner world’ is intrinsically more interesting than what is around us. It isn’t.

Rupert Loydell

The Letter Press: https://www.theletterpress.org/shop/

A film about the collaboration between Garry Fabian Miller and Dovecot Tapestry Studio: https://vimeo.com/191490217

Arnolfini details about Garry Fabian Miller, including videos of his Bodleian Library lecture series ‘The Light Gatherers’, and the BBC Radio 4 programme ‘The Last Exposure’: https://arnolfini.org.uk/artists/garryfabianmiller/