Their songs are like eating honey. You don’t need much to be satisfied. They’re the Fab Two, partners-in-rhyme. Two guitars, two voices in harmony. Their music adds a touch of wonderful to your day, with the intimacy and precision of a Paul Simon song matched to harmonies that ache with Everly Brothers cadences. The humorous lyrics to ‘I Stay Away’ reference Don & Phil, and Paul & Art. So the odds are stacked, their voices create the perfect storm.

In a time when radio presenters are valued more as familiar TV-faces than for their commitment to music, Mark Radcliffe is old skool. He cares. Always has. And while his Radio Two Folk Show and shows with Marc ‘Lard’ Riley, or his 6music partnership with Stuart Maconie are literate and informed, Mark has always nursed his own music aspirations. As he tells the story in his Showbusiness: Diary Of A Rock ‘n’ Roll Nobody (Hodder Headline, 1999) he evolved in bands through glam, until the Punk revelation took him further ‘along the rocky road to anonymity’ by spewing Ridiculous & Jones, plus a group called She Cracked which also included a genuine ex-Buzzcock. Then the Ska-tological Bob Sleigh & The Crestas, who almost mastered the finer points of ‘starting and finishing together,’ until eventually he moved into the Shirehorses.

David Boardman, as well as being a fine guitarist and songwriter, is an artist of distinctively modernist paintings. Mark met David in ‘The Rose & Crown’ public house in Knutsford. That’s appropriate, because the duo’s first album – First Light (2024) narrates of the luring warmth of ‘Cheese & Beer’, the pleasures of wasting companionable time together in the local hostelry, as well as ‘Last Orders’ in which ‘he goes to the bar to get out of his brains’ in a numbing alcoholic blur. But there’s also rippling rolling guitar-strum that walks into the gloaming amid curling dobro, ambling at the first light of dawn before the world has woken. That first album-art shows the duo – Mark’s dog to hand, sitting on a rocky outcrop overlooking endless northern landscapes, where, with a little imagination, you can see the riverboat from Salford Quays.

The Mark & David Show is a joy, their amiable rapport is obvious from their verbal interplay.

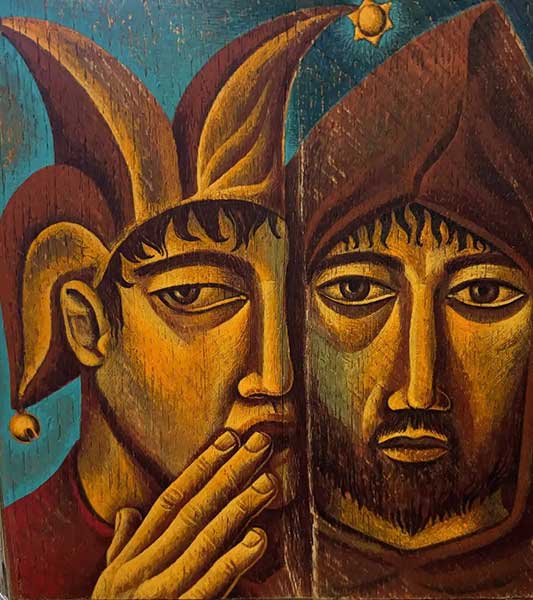

The second album – Hearsay & Heresy (2025), is a more integrated more cohesively focussed venture. Although cover-designed by David, the medieval art of jester whispering to the monk is by Michael Cook. There are more wistfully nostalgic harmonies, of journeys never ended, circles unclosed, suns that never set. Opening track ‘Merchant City, Driving Rain’ has soft urban images that melt in shimmers of rain, with a touching ‘mind how you go, my old friend’ refrain. But weren’t Paul & Art once ‘old friends, sat on a park-bench like bookends’ and look what happened them! Then Mark sings ‘On Euston Road’ ‘where the River Fleet flowed.’ He’s a hick from the sticks, trading northern skies for city gridlocks, ‘trying to look like some tortured soul, a troubadour, pure Rock ‘n’ Roll.’ The track closes with faint traffic sounds.

‘Steal The Sea’ is a major track that looks back to ‘when I was just a scrawny kid,’ but then delves yet further back to the year 1882 when the Cotton Kings of landlocked Manchester conspired to steal the sea from Liverpool by building the Ship Canal, so that they ‘will rule the world, once we’ve stolen the high seas.’

Mark’s latest book Et Tu, Cavapoo (2025, Corsair Books) tells of his three-month sojourn living in Rome with wife Bella and dog Arlo, a time which is also recalled in ‘At The Bar San Calisto’ with ‘Django sound unchained’ violin washed down by red wine and strong coffee. The bar is located in the corner of the square amid ‘garbage and graffiti,’ and while the song is the more lively source of the album title – Hearsay & Heresy, there’s the disquieting truth that ‘I will never know your secrets and you’ll never know mine.’

Through to ‘The Not So Grand Hotel’ which opens with the a-cappella ‘is this the last farewell’ and seems to paean the soft decline of England into senility, where the ‘human contraband’ of asylum seekers are besieged by rioters in a budget hotel, ‘where the wild things are.’

Stepping back to the first album, ‘Tear It All Down’ is a more affectionate memory of the old town with caricature character-sketches, before the wrecking ball demolishes it all. And the country-accented ‘Buy The World A Drink’ with banjo, linking into ‘We Saw The Light’ – which is a tribute to Hank Williams. On YouTube there’s a clip of the duo doing a version of Hank’s much-covered ‘Your Cheating Heart’, and it works immaculately. Honeyed tones in harmony.

Here and now, pictures hang on the wall behind them. Birds in flight. A stylised galleon in full sail. A timetable. A framed RCA record. David slurps tea from a Tintin mug.

Mark: Hi! Can you hear me? Yeah, great, OK good. David’s here (David waves).

Andy: It’s great to have the opportunity of speaking to you both.

Mark: That’s really kind. Thank you for your interest, Andrew. So what are we doing this for? Because we can’t remember (he slouches forward, resting his chin on the palm of his hand). Obviously we’ve done so many interviews – y’know, New York Times, all the prestigious publications, The Tonight Show With Jimmy Fallon, we’ve done ‘em all, we just get mixed up which is which. It just gets to be a blur.

Andy: The Rock ‘n’ Roll lifestyle can get so tedious at times.

Mark: But this is the big one, obviously. Where are you, Andrew?

Andy: West Yorkshire, near Wakefield.

Mark: Well… OK. We were in Ilkley last weekend. Is that near you?

Andy: Not too far away. Congratulations on a fine album. You must be very pleased with the way Hearsay & Heresy turned out?

Mark: Thank you very much. Yes… we were. It was Dave’s fault. We did the first album very quickly, which is the way I like to work. And then Dave said ‘that was fine… but’ (he turns to David) you wanted to do this one more… he takes more care than me.

David: Well, I thought it perhaps deserves a little more consideration. So, it took us a little longer on this one.

Mark: We did. We did.

David: Three days instead of two (laughs).

Mark: The first album was kinda songs we’d been doing with other bands and things, with a couple of new ones. But this was all new for this duo, so it felt like… in a way it’s the first album proper.

Andy: You do need that balance between consideration and spontaneity.

David: Well, hopefully we’ve got that, because I like to spend forever tinkering with stuff and doing it a thousand times. Mark gets bored after two takes. So we tend to… it’s quite a good balance, really. He tempers my excesses, and I encourage him to give it a bit more thought than he would normally.

Mark: I think it’s still quite spontaneous, because we’ve found by doing these… we can only really record the vocals together, because what we’re after is like two halves of one voice. So that’s quite spontaneous. We don’t spend an awful lot of time on the vocals, which sounds counter-intuitive really, but that’s the bit that’s quickest. So, we get the basic guitars and vocals down very quickly. And then Dave and our producer Jake (Evans) will spend a long time adding little details, which I do like… we’ve drawn the analogy of a painting really, because Dave is an artist. I sort-of think it’s finished when the figures are in the foreground, whereas Dave and Jake quite rightly say ‘yeah, but what about all the things in the background? What about the Turner-esque sky that’s got to go on this?’ And so, I do appreciate that, but sometimes I’ll take me dog to the studio and I’ll go for a walk while they mess about for ages with something.

Andy: That’s the dog on the cover-photo of the First Light album?

Mark: It is. That’s Arlo…

David: He’s here somewhere (looking around the room).

Mark: Oh! He’s under the desk here! And he’s got a book he’s co-authored with me, coming out in August, about our time spent in Rome…

Andy: That is a future question I’ve got lined up.

Mark: Fine, fine.

David (turns to Mark): Are you Arlo’s ghost-writer?

Mark (laughs): Yes, I’m Arlo’s ghost-writer.

Andy: Hearsay & Heresy does seem a more integrated and cohesively focussed album than First Light, it’s got that kind of yearning wistful quality.

Mark: Do you mean depressing, Andrew?

David: We do like the wistful side of music, but I think it’s got quite a balance of stuff. It’s got some slightly more jaunty things as well…

Mark: It’s got one slightly jaunty thing (indicates with a single finger).

David: One jaunty thing, which is neatly placed halfway through so people don’t get utterly depressed by the end of it.

Mark: I suppose the stuff that we do tend to write is kind-of reflective. I tend to write… basically I write the words, Dave writes the music, it’s not quite as simple as that, we have an input to what each other are doing, but I think at the age I am, you naturally veer towards reflective things. I’m 67 next month, and I suppose there is some nostalgia in there, and there is some wistfulness, but some of it is just pretty straightforward, really. The opening track – ‘Merchant City, Driving Rain’ was just literally… it is what it says it is, it’s just about getting caught in a storm in Glasgow, it’s not particularly profound in any way. But I think, when we wrote that song – which we wrote very quickly when we at ‘Celtic Connections’, we’d been to see the Milk Carton Kids at the Pavilion Theatre. We came out and it was blowing this almighty hooley, it was really fearsome, it was scary, wasn’t it…?

David: It was, very scary.

Mark: There were literally scaffolding poles clattering off buildings and things, you had to walk down the middle of the street, and I got back to the hotel and I couldn’t sleep, so I wrote that and then eventually I went to sleep and I woke up in the morning and read it, and I thought ‘that’s pretty good, that.’ And we were playing that night, so I gave it to Dave and said ‘this is new, let’s play it tonight while we’re in Glasgow,’ so he had to write the music, he had about three hours in the afternoon to write the music…

David: While you went for a kip!

Mark: I went for a kip, and when I woke up Dave said ‘I’ve done it.’ But I think when we did that we felt like we’d… sort-of, I don’t know, perhaps taken a step up in the writing for the duo – didn’t we? (turns to David). That song was quite key, I think.

David: It was. It was a key tune. But I think it was one of the first that we’d written specifically for us. Just to sing on our own, rather than writing for our previous bands. It sort-of solidified the sound and the harmonies and stuff, so it was quite a pivotal song.

Andy: There’s a touching ‘mind how you go, my old friend’ refrain. But weren’t Paul & Art once ‘old friends, sat on a park-bench like bookends’ and look what happened to them!

Mark: Yes, I suppose. Well… there you go. OK, well… we’ll take that, Andrew. Yeah, let’s go with that. But no, it wasn’t really. Honestly, it’s very good of you to try to read more into it than is there. But it was just ‘mind how you go.’ It’s like ‘bloody hell there’s gonna be a scaffolding pole falling on your head if you don’t watch yourself.’ It was really as simple as that. But we were there for ‘Celtic Connections’ and we were sort-of swept up in the atmosphere of that great Festival, and all the landmarks of Glasgow, which is a city I like a lot, and it really was just a postcard from the centre of a hurricane in Glasgow. No more, no less.

Andy: Then Mark sings ‘On Euston Road’ ‘where the River Fleet flowed.’ He’s a hick from the sticks, trading northern skies for city gridlocks, ‘trying to look like some tortured soul, a troubadour, pure Rock ‘n’ Roll’.

Mark: That’s what ‘On Euston Road’ is about. It’s exactly about that. That’s the second track. That’s very autobiographical about when I went to London.

Andy: ‘Steal The Sea’ is a major track that looks back to ‘when I was just a scrawny kid,’ but further back to the year 1882 when the Cotton Kings of landlocked Manchester conspired to steal the sea from Liverpool by building the Ship Canal, so that they ‘will rule the world, once we’ve stolen the high seas.’

Mark: Yes, well, I don’t live far from Manchester, but that came about because I spend a lot of time in Salford, working for radio programmes, and unusually… I was doing something, there was a reason why I was staying that night over in Salford, and I was in a big kind-of tower-block hotel, and I was looking out over Salford, which was… we’d been talking about it on the Folk Show about the seventy-fifth anniversary of ‘Dirty Old Town’, y’know, how Ewan MacColl came back to the city to sing, so I was looking out at that and thinking ‘what would Ewan MacColl think about this?’ and I’d also just read Walter Greenwood and Love On The Dole (1933) which is a classic book, all set in the streets of Salford, but also obviously I was looking at the Ship Canal and thinking back to when I was a kid and I thought Manchester was on the coast because when I came in from Bolton there was docks, so I thought well that must be the sea, why wouldn’t I think that? And then it just started to strike me how amazing it was really that the Cotton Barons of Manchester, resenting paying dock fees to Liverpool, decided to bring the docks inland, I mean they dug… they literally got a thousand shovels and dug the sea forty miles inland, and I’m thinking it’s a bit of a low trick in a way, isn’t it? So yeah, that song was really about that and sort of feeling – not exactly that I had a foot in both camps, but that I can remember… because obviously you know I wasn’t there in 1882, I’m not quite that old when they started building the Ship Canal, but I do remember that being a complete wasteland and looking very like a LS Lowry industrial landscape, and then being part of Media City with all this kind of glass and chrome towers. So I do feel like I kind-of had a foot in both camps really, and so – yeah, that song was very much just the history lesson really.

Andy: Manchester is a great Rock ‘n’ Roll city, from Freddie & The Dreamers right up to Oasis of which you’ve been part of.

Mark: Yeah, yeah, I mean I’ve been part of Manchester and Manchester’s kind-of… I came from Bolton to University there in 1976 and I did spend some time in London, which is a subject of the ‘Euston Road’ song, but yeah Manchester has been the kind of background and soundtrack to my life I guess, and its changed a lot now so that when we go there now we can’t find our way around can we? everything that used to be like… you know, Oh, just park on that piece of wasteland, now has two-thousand flats on it, and you can’t park anywhere, we get the tram now don’t we? We’re a bit frightened by driving into Manchester, but yeah, I still love it, but the part that I know as Manchester is like the centre of a much much bigger more sprawling City now, which is great, you know, things change, things move on. I mean that’s actually the subject of another song on the album called ‘Down The Steps’, which is set in an old pub in Manchester which is a bit of the old Manchester really, but it’s trying to say ‘I’m not crippled by nostalgia’ you know, it’s trying to say ‘we know life moves on, we don’t want things frozen in time, but that there’s precious bits of it still there in the midst of everything that’s changed.

Andy: You’re right about the luring warmth of wasting companionable time together at local hostelries, from ‘Down The Steps’ right through to ‘Cheese And Beer’ and ‘Last Orders’ on your first duo album.

David: Yeah, yeah, definitely a thread developing there…

Mark: You could do a pub-map of Manchester, we should give that with the album, so they can fold it out and find where all the places are. Yeah ‘Last Order’ was the Lass O’Gowrie pub…

David: We’re going to extend that to pubs around the country for the next album.

Mark: Yeah ‘Last Orders’. And ‘Cheese And Beer’ was a pub called the ‘Mark Addy’ on the Irwell, but that got flooded and it’s not there anymore. No, it’s not there (spoken to David), it’s never re-opened.

David:… really?

Andy: In the boozer is a great way of wasting companionable time together, but it can also be a detriment as well. I think of the likes of Gerry Rafferty and his problems with alcohol.

Mark: Yeah well… I mean, I really… we actually talk in the show a bit about something we call the two-pint axis. That if you’re feeling down or whatever, even if you’re feeling great, if you go into a pub and you drink two pints a beer the world shifts slightly on its axis, things feel slightly different. But we do think that you kind-of move away from that on three points, and so neither of us… yeah, we like going to the pub and having a couple of drinks but neither of us are real ‘caners’, especially not me, and so we do…

David: We’re getting on a bit.

Mark: We’ve had experience of friends with those sorts of problems. Though thankfully, mercifully neither of us are anywhere near that. But yes, you’re right.

David: We are quite in tune in that way.

Mark: Yeah, we are. I mean ‘Last Orders’ – which is the song you mention, is very much a cautionary tale about drinking. Drinking’s at the centre of it, but it says – you know, there’s always some Bar that is open, some other fool to propose a toast. And so, yeah, we are aware of that, it’s not – like yeah, it’s not a glorification of drinking, although it is acknowledging that it’s really nice to have a pint in a nice pub with friends and the world changes slightly, doesn’t it?

David: I mean, ‘Down The Steps’, which is about Sam’s Chop House… yeah, I mean that’s a little doorway into the past really, if you ever get the chance to go, it’s an incredible place, where you literally go down these steps, and it’s like stepping back in time, and although we’re not crippled by nostalgia it’s nice to spend a bit of time in there, and you’ve even got LS Lowry standing at the bar…!

Mark: There’s a bronze statue at the Bar, yeah.

David: And so – you know, just to have a pint with Lowry…

Mark: And yeah, I might only go there two or three times a year, and we probably have two three pints, but that’s enough for it to just kind of top you up, really, on what it brings to the table.

Andy: David, who were your guitar icons when you were starting out, you mentioned Django Reinhart at one point?

David: Yeah, well, I mean…

Mark: Eddie Van Halen wasn’t it?

David: (Mark gets up and leaves David to speak) Yeah, Eddie Van Halen mostly, I went through a big Heavy Metal phase as a teenager. With Django, I sort-of got into a bit more jazzy stuff in more recent years. I mean from my school days it was – you know, all the classic stuff after the Heavy Metal phase, it was all – Jimi Hendrix and Eric Clapton and all those guys and then some of the BritPop guitarists and stuff. But it’s a mixture, everything from John Martyn to Ronnie Woods to Django Reinhart, I suppose. I mean, like, Django Reinhart was a big influence on the ‘At The Bar San Calisto’ track off the new album, where we were trying to, sort of, evoke that kind of Gypsy jazz feel. Because when Mark sent me the lyric, he was in Rome, and he’d written this lyric sat in a Bar… another Bar, but only having two pints! And he sent me this lyric over on an email, and straight away you just sort of imagine this – you know, I don’t know, Mediterranean kind of Gypsy jazz kind of feel, so straight away I was thinking about people like Django Reinhardt or Stephane Wrembel, you know. I mean, I’m not putting myself in those… you know, I’m not saying I was as good as those guys, but it was that feel, you know, and I think that track turned out really well…

Mark (returning): Yeah, I think ‘Down The Steps’… you’ve already mentioned John Martyn, ‘Down The Steps’ is really a direct lift from John Martyn, with ‘Danny Thompson’ on the bass and a little bit of electric piano. So y’know, John Martyn definitely. John Martyn is definitely a big influence on everything that we do. And probably in terms of the songs and that kind of wistfulness about it, Nick Drake. I think there’s quite a lot of Nick Drake influence in there. I mean, on the first album… ‘First Light’, that title song is about insomnia, but it’s also about Nick Drake as well, there’s a lot of his song titles in there, so yeah, Nick Drake features quite heavily.

Andy: Where do the Everly Brothers fit in? You mention Don & Phil in one of your songs.

Mark: Well yeah, I think it was like Dave said… this started when we were still in a band together called Fine Lines, and I used to write the words and Dave used to sing. I used to play drums in that band too. But when it was Lock-down, and we couldn’t get the band together – there was seven people in it at that time, and we couldn’t get them together, so Dave and I carried on writing and, just to try the songs out, we’d sit with two acoustic guitars and sing…

David: Two metres apart!

Mark: Yes, two metres apart, with visors on! There was another singer in the band, a woman called Zoé who sang with David. So I’d try and sing her part just to see what it would sound like while we couldn’t get the band together, and we did that quite a while, we started thinking ‘is this quite good? is this alright?’ We quite liked it, and we started thinking about the Everly Brothers and Simon & Garfunkel, and particularly the Milk Carton Kids who we mentioned, and Gillian Welch & David Rawlings, those people who really love two voices. And I mean, again like Dave says, we’re not putting ourselves in the league of any of those people at all, but we like it. And we also liked the idea that you could go and do a gig with two acoustic guitars in a car rather than seven people with drum-kits, keyboards, amps – yes, and you might even make a tenner each at the end of the night, rather than it costing you! So that was how that started really and so the band carried on – Dave’s still got the band. I’m not playing. When it comes to it, I’ll still write Dave words and things, but I don’t…

David: You’ve retired from drumming.

Mark: I retired from drumming. But that was how it came about, and so it was in Lock-Down really, where the Everly Brothers… I really kind of thought, yeah – they’re the best that’s ever been at that two-part thing.

David: I suppose, as soon as you start with a duo, and it’s only a male duo, you think about harmony singers – and you think about who’s the best at this? the Everly Brothers instantly spring to mind. Simon & Garfunkel is another one, and obviously we just love that music anyway, so they just became natural touchstones for what we were doing. And then Mark introduced me to the Milk Carton Kids and he said ‘Oh, check these out, these are great.’ And ‘Oh God yeah, brilliant guitar,’ but it’s a very self-contained thing, they don’t need anything else, and we were quite… having been in these huge bands, we were quite attracted to the idea of a self-contained unit. So yeah, it had obvious appeals.

Mark: So I think even when we made this record, we didn’t want to make it sound like a band. We didn’t want to put drums and things on it, we wanted it to sound like two guitars and two voices at the middle of it. But – like I said before about the painting, you know, it’s just adding detail to it to make it a little bit more produced, to give it a bit more sonic richness in a way.

Andy: Also, on First Light you’ve got a song about Hank Williams, and also on YouTube I found a clip of you doing ‘Your Cheating Heart’ together.

Mark: We still do that. Yeah, we love Hank Williams. I think he’s the first Rock ‘n Roll star, he has the tempestuous lifestyle and the drinking and the flashy suits, and all that. His is a really sad story. But I do think his songs are – you know, they’re so simple, they’re really so simple, but they’re absolutely brilliant. They’ve almost become folksongs. They’re almost traditional folksongs. I mean, ‘Your Cheating Heart’ is the great song of betrayal… you know, you’ll get what’s coming to you. It just says so much in so little. I mean, musically they’re simple, although the solos you get in Hank William songs – you know the fiddle and the steel are superb, the solos are absolutely majestic. Musically it’s pretty sophisticated, but the basic structure of the songs is very simple – you know, the three chords and the truth thing as Woody Guthrie might have said. And they’re not big subjects, they’re not political songs like something like the Woody Guthrie thing, but they are universal themes, of love and loss and heartbreak, things that everybody can identify with. And sometimes I think… sometimes I think, we’re drawn towards things which don’t seem to be trying too hard. I’d rather think I’m drawn to music that leaves you space to think for yourself, rather than being told what to think by a song. I think that’s right. I mean there is one sort of more specific protest song which closes this album, but that’s it, I think, just one.

Andy: This is the ‘heresy’, this is the ‘Not So Grand Hotel’ track.

Mark: Yeah. Yeah, ‘cos that was unusual. The reason I don’t like writing songs with that kind of a big message, is I don’t think I’ve got anything to tell you or anyone else that you haven’t already thought yourself. I mean, who am I to tell you what to think? But we were just watching the pitiful firebomb in that hotel full of asylum seekers, and thinking ‘god, you know, has it really come to this?’ You know? For whatever reason those people came… I mean, if a child of mine was in that situation, god forbid, and went somewhere, I’d like to think that people received them with a good deal more kindness and understanding that that, even if they disagreed with what they’ve done. I just think, the idea that someone would try and firebomb a hotel with families and children inside…

David: In whatever shape or form.

Mark: And so, yeah, that was kind of written as a sort of a shanty, really, just a sailor setting out on the sea, but then it becomes clear that he’s made an illegal crossing of some kind, I mean, I didn’t go into the details behind it, I just wrote it. But it was really… that was just one circumstance when I thought – you know, I just feel I need to put something down about this, because it just felt such a low point in the country we’re living in. Really, have we come to this? It was just that.

David: Although the irony is that the music to that song was written in a Five Star Hotel in Portugal, true story.

Mark: Room service hadn’t been suspended!

David: Room service was definitely still on.

Mark: We went to the Costa Festival, we played there in the Algarve, and he was writing the music in his room in the Five Star Hotel, yeah ironically.

Andy: The song ‘At The Bar San Calisto’ was about the time that you were living in Rome, which is covered in your forthcoming book Et Tu, Cavapoo? (August 2025, Corsair ISBN-13: 978-1472160348).

Mark: Oh, nicely plugged Andrew, yeah. Last year for three months myself and my wife Bella and our dog Arlo, we drove down to Rome in our VW Beetle Convertible, and we spent three months there. Yeah, which was amazing, it’s the greatest city in the world, I think. So, every day we just wake up to the light and walk around the city and go and see the Caravaggio’s or the Michelangelo’s or whatever we’d decided to do that day. But just down the block from where we rented this little flat in an area of Rome called Trastevere was this quite scruffy bar called the Bar San Calisto, and it’s a – sort of, like, it’s one of the great bars, I mean, there are tourists in there but there’s a lot of locals and a lot of people who are kind of characters and quirky, and you know you’d have to say, probably quite a lot of people for whom life hasn’t worked out quite as they’d expected. It was dirt cheap and inside it was… you didn’t want to go inside really, it was just two little rooms with lino floors, so you sat outside and it was just an ever-changing kind of pageantry of human life, really, and people walking by. The tables were Peroni, but they’d been there so long in the sun, and the odd shower, that the logo was almost worn off, and all the tables were plastic, it was just not ‘sheshe’ at all, but it’s just on a corner, a special corner just off the square of Santa Maria in Trastevere. And I just sat there for hours with Arlo on my knee just quite often drinking coffee, you know, and just watching the world go by. And so I wrote this song there. It was sunny every day, and I sent it to Dave last spring, which – if you remember, wasn’t sunny every day was it?

David: No, it was pissing down every day! so I replied ‘I’m glad you’re having a good time.’

Mark: So that was it, and then Dave said about the Gypsy jazz thing. He mentioned Stephane Wrembel because one of our favourite films, in fact probably your favourite film, is Lost In Paris isn’t it?… no, Midnight In Paris (2011) the Woody Allen film, and there’s a sort of Spanish gypsy guitar thing by Stephane Wrembel that goes all the way through that movie. We absolutely loved that. So yeah, there was a bit of that feeling of the Gypsy jazz in the city that came from that as well. Yeah, so it’s… I sent the words to David and said, I feel a bit of Gypsy jazz going on here, and so we did, yeah.

Andy: I like the line in your song ‘I will never know your secrets, and you’ll never know mine,’ which says that no matter how close you are in a relationship, there’s always going to be a slight separation.

Mark: I guess you’re right. I mean it wasn’t really about that. It was about the fact that – again, this pub thing, where you can strike up a conversation with people. But you’re not a local, you will never know their history and all their stories, and they will never know yours. But I quite like that. I mean, I quite like those sort-of shallow surface conversations. You know, not everything needs to be a deep heart-to-heart. Some of it is just ships passing in the night really. Sometimes you’ll just hook up with someone who you meet by chance. And you’ll have an afternoon in a pub, and it’ll be a right laugh, and you’ll never see them again. But I think, in some ways, the sense of enjoyment you get from that is because you know it’s a kind of relationship that’s completely ephemeral, without responsibility. You know, you just talk rubbish to someone, you might get little details of their lives, but you know that then you’ll move on and it’ll never happen again. And I quite like that. So it was it was about that, really, but you’re obviously a deeper thinker than me, Andrew and you’ve read more into.

Andy: You are familiar with interviewing and being interviewed, Mark. You know, with artists on your radio show. You know how the interview process operates.

David: You’ve done one or two.

Mark: Hmm, I’ve done one or two, yeah! I have.

Andy: In some ways when you’re answering questions, it can make you think about things that are otherwise largely an intuitive process. When you’re creating music it’s an intuitive process, but when you are being interviewed, you have to articulate it.

Mark: Yes, I suppose so, I suppose when you’re interviewing… what I hate to hear when you’re interviewing, there’s a lot of interviewers who can’t resist putting themselves into the question really. I’m always, when I’m interviewing someone, I’m like – you know, I’m on my radio show, people have heard plenty about me, this is someone else. And the other thing that annoys me about interviewers, is that they don’t listen, they have a prepared list of questions, and someone will say something which will then prompt what should be another obvious question, but they don’t go for it, they move on to the next one on the list, you know they’re not listening. So I think that an interview is a structured conversation really. You’ve got things you want to ask, you’ve got things you want to know, but if someone says something that you didn’t know, then you might want to explore that. I think you’ve got to… you know, be aware of that. So, for example, if I was to tell you, to just mention in passing, Andrew, about my freediving experiences jumping off the world’s highest landmarks, you might want to pick up on that, if it wasn’t a lie. (David chuckles.) That’s just a theoretical example, I’ve got a fear of heights, I hate them!

David: You’d be hopeless!

Andy: Another thing, I was thinking about how John Peel had his own record label, Dandelion, but the BBC didn’t allow him to play Dandelion records on his show, because that would constitute a conflict of interests. So you’re in a similar position in that you’re not allowed to promote your own records on your own radio shows.

Mark: Well, thank God for that, you’re right, I mean – that’s fair, I accept that, and I think that that’s right.

David: We’ve totally shot ourselves in the foot. Haven’t we?

Mark: We have. Because the only show on Radio Two that would play us, is one presented by me. And I can’t play us, yeah.

David (grinning): So we’ve had it basically!

Mark: But you’re right. The rules are, that if I’m on a BBC contract, I’m not allowed to play anything on my shows that I personally profit from. And I think that’s fair enough. That would be wrong, clearly wouldn’t it? The idea that I would do the Radio Two ‘Folk Show’ and say ‘well I’ve listened to everything that everybody’s released this week and the best things I can find are three or four songs by me and David.’ And so I don’t have a problem.

David: I think it would be a much better show.

Mark (much laughter): I totally accept that, and you know – the upside of it is that… I have met other people who have radio shows, and like, you can get the music to friends and say ‘what do you think about this?’ Sometimes it’s a bit difficult, sometimes it’s less of an advantage than you might think. People put people in boxes, sometimes people think that I’m a DJ presenter interviewer or whatever, and that they find it quite hard to separate that from me doing what I’m doing with David. Which is unfortunate in some ways. But, I think that we’re all capable of doing many things aren’t we? Dave is an artist as well. We’re all smart people, aren’t we. We can all do more than one thing at a time.

David: What people don’t understand is how you can possibly do more than one thing.

Mark: I know…

David: Like Bob Dylan for example, he’s a painter as well. But it’s like they think, his paintings can’t be any good because he’s a singer.

Mark: Yeah, the concept of the Renaissance Man. And I’m not suggesting that we are Renaissance Men! But you know what I mean. So yes, you can make some good contacts and everything, but it’s not always the advantage you think, it might even be a disadvantage, I don’t know.

Andy: I read your show business memoirs, and you’ve been in a number of bands across a number of years, charting different phases of your career (Showbusiness: Diary Of A Rock ‘n’ Roll Nobody, 1999, Sceptre/ Hodder Headline, ISBN 0-340-71566-9).

David: You’re not new to this, are you?

Mark: Yeah, I’ve always done it, really, it’s part of who I am. So, music has always been the best hobby in the world. It’s a hard job to have, a lot of the time, but this is just a kind of glorified hobby. We put as much into it… we put far more effort into it than we should, considering it as a hobby. But it’s like people improving a golf game or something, you know, you kind of get obsessed with it. And so you know making a record, writing songs is something I’ve always done. I mean… in your younger days when you’re a kid you think ‘Oh it’s only a matter of time before we headline in Wembley’… well, we don’t think that’s gonna happen anymore, do we? Well, we might? No, it won’t! We’re more realistic about it now. But you still never lose that little bit of, that little flicker of ridiculous hope that maybe, maybe somehow Tom Cruise will hear this album and put a song from in the next Mission Impossible movie. You never know. The only thing that’s for sure is if you don’t try, nothing will ever happen.

Andy: I think this is the last Tom Cruise Mission Impossible (2025) movie, it’s called Mission Impossible 8: The Final Reckoning, so there’s not going to be any more.

Mark: Good point, Andrew. You’ve made a good point there.

David: It’s just bad having to do it.

Mark: I told you that, I told you don’t bother Tom Cruise with it, I told you that when you stopped him in the Services.

David: I probably shouldn’t have phoned him.

Mark: I know, yeah, I told him Andrew, what can you do?

David: We could try George Clooney?

Andy: Is there anything else you want to get across, that we’ve not already talked about?

Mark: We’re looking forward to playing in Cornwall in the summer, so we’ve been in Saint Austell and Penzance and Chagford…I actually think Chagford’s over the border in Devon? Maybe – I think so. We’re playing down there, so that’s new for us. So we’d like to thank…

David: We’re playing in Birmingham tonight.

Mark: Yeah but this won’t go out, will it? He’s not gonna publish it today, is he?

David: Scrap that!

Mark: I’ll tell you something, Andrew, getting people to gigs is quite difficult these days. People have not got the money and everything, and we live in a funny world where people will happily pay a thousand pounds to see Taylor Swift but they won’t go to a £10 gig down their road. I mean, I understand that people want to go to big events, I understand that, but I’ll tell you one thing, I don’t know why it is, that we do really well in Yorkshire.

David: We’re massive in Yorkshire.

Mark: Our Yorkshire gigs sell out. And we can’t work it out at all…I mean, I’m a Lancastrian and he’s a Geordie, you know? It’s really weird, but thank you Yorkshire.

David: Maybe because Yorkshire is the halfway point between the northeast and the northwest?

Mark: Maybe, but we do really well in Yorkshire, like…Otley.

David: God bless the people of Yorkshire.

Mark: They organised a tickertape parade for us in Otley.

David: It was like the Beatles.

Mark: It was. So thank you Yorkshire, you’re the best.

Andy (laughing): I just realised, it’s Bank Holiday Monday today. Don’t you two have beaches to go to or something like that?

Mark: We’re going to Birmingham. We’re going to be playing the Kitchen Garden Café in Birmingham’s Kings Heath tonight, and then a nice gig in a barn in the Cotswolds on Tuesday, and then Milton Keynes on Wednesday. So yeah, we’ve got a little mini-jaunt to play some songs and hopefully sell some albums. So yeah we’re looking forward to it…

David: And we’ll have two pints in each venue.

Mark: Yes, we’ll have those two pints.

Andy: Thank you for your time, both of you.

Mark: Oh, thanks for your interest, Andrew. Cheers mate. Thank you very much indeed, and have a good day yourself.

BY ANDREW DARLINGTON

FIRST LIGHT (Parade Recordings, February 2024)

1. ‘First Light’ (5:08)

2. ‘Tear It All Down’ (3:31)

3. ‘Buy The World A Drink’ (4:27) ‘sometimes I’m colourblind, sometimes I just see red’

4. ‘The Homesick Café’ (4:12), ‘home thoughts abroad’ ‘there’s no light in this tunnel of love’

5. Cheese And Beer’ (4:56) ‘another afternoon that ended on our hands-&-knees’

6. ‘Out On The Shore’ (5:11) ‘somewhere in the sandstorm there will still be you and me’

7. ‘We Saw The Light’ (3:46) ‘the drifter and the troubadour’ to Hank Williams

8. ‘I Stay Away’ (4:51) ‘it’s being apart that keeps us together’

9. ‘On The Town’ (4:40) ‘never again the runaway, never again the foreign sky’

10 ‘Last Orders’ (3:28), there’s laughter, banter, and flamenco guitar as ‘he goes to the bar to get out of his brains’

HEARSAY & HERESY (Talking Elephant, May 2025)

1. ‘Merchant City, Driving Rain’ (4:22)

2. ‘On Euston Road’ (5:04)

- ‘Steal The Sea’ (4:26)

- ‘The Long Ridge’ (3:26), harmonica by Les Hilton, ‘a Lone Star state of mind’ walking the wild country.’

- ‘At The Bar San Calisto’ (4:05), fiddle by Clare ‘Fluff’ Smith

- ‘Down The Steps’ (4:38), tinkling piano by Gary O’Brien, he’s ‘not crippled by nostalgia’ despite references to Corned-Beef Hash & the Barnsley Chop

- ‘Never Had The Last Dance’ (4:51), piano by Gary O’Brien, ‘so many stories still unfold’ ‘every summer has to fade’

- ‘Moon Fishermen’ (3:55), arhythmic shuffle-beat

- ‘Right Side Of The Tracks’ (3:59), melancholy harmonica by Les Hilton, ‘the missteps and the long ways round’

- ‘The Not So Grand Hotel’ (4:55)

.