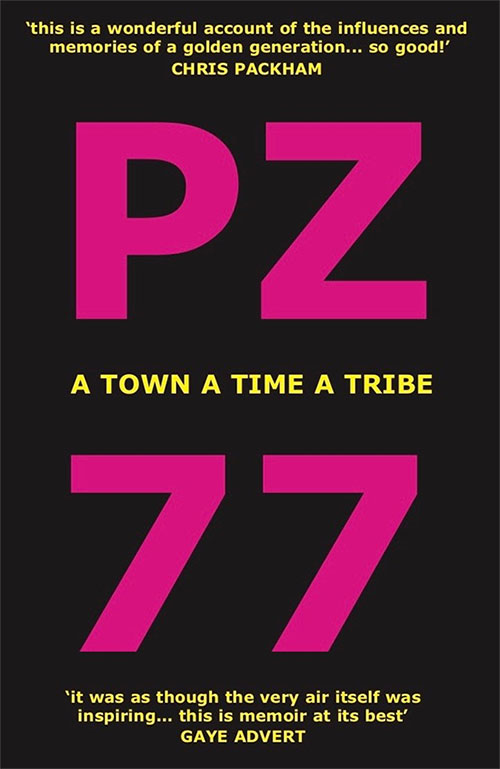

PZ77. A Town A Time A Tribe, Simon Parker (391pp, £12, Scryfa)

Whole World in an Uproar. Music, Rebellion and Repression 1955-1972, Aaron. J. Leonard

(319pp, £12.99, Repeater Books)

Now and Forever. Towards a Theory and History of the Loop, Tilman Baumgärtel

(389pp, £23.99, Zero Books)

If you look hard enough, every town has its own history, its own web of events, places and moments, worthy of attention. Penzance in 1977 saw The Ramones visit and shake things up, and PZ77 is an oral history of that summer and beyond, when punk arrived in person and Cornwall came alive with musical ambition and subversion. Simon Parker has collected and shaped an oral history from the recollections of over 90 people, organising them into chapters as a playlist, each ending a named track and instructions to PRESS PLAY.

The book is at various times repetitive, rambling, nostalgic and endearing; by the end the reader will know the back streets, cafés, pubs and venues of this town at the end of the (train) line like the back of their hand. Weaving throughout the roll-ups and coffee-cup lingering, the drinking, posing, love affairs and teenage groups are musical missives from elsewhere: Van de Graaf Generator, Barclay James Harvest, Hawkwind, Genesis and Greenslade, gradually giving way to the new sounds of Talking Heads, Elvis Costello, The Damned, The Adverts, The Stranglers, The Vibrators in addition to The Ramones.

It’s hard to equate comments which compare The Ramones to Status Quo (quite rightly imho) to the effect the band seemed to have had on Penzance where, according to Jeremy Beeching, ‘[t]he unfolding punk world seemed like another galaxy, with 1970s Cornwall being very cut off’. But in retrospect the world of music, fashion and behaviour certainly changed, with shocked parents, energised youth and confused venue managers having to process and adapt to the sight of ripped skinny jeans, torn leather jackets and the sound of short, noisy, angry songs, for themselves.

Once again, it’s clear that one of punk’s most important achievements was the opening-up of rock to those without traditional musical skills, a giving of permission to have a go and speak out and make music for yourself. So much of this book is not only about fandom and record collections, but about local bands forming and breaking up, going on tour, practicing, and embracing DIY composition, management, promotion and fashion. Interestingly enough, just as London post-punk often drew on reggae, Cornish punk seems to have been happy sharing space with the folk music and singer-songwriters prevalent at the time. Maybe it’s just the hippy vibe that to this day underpins and sometimes sabotages Cornish ambitions and businesses?

Whatever the case, PZ77 is an entertaining and witty, if slightly self-mythologising, history of one town’s subcultures. It’s a lively, personal, and engaging read, which re-presents and remembers a time many of us lived through.

Chronologically, Aaron J Leonard’s book ends before PZ77 even starts. It documents American society’s attempts to suppress and censor the music it did not understand or comprehend, along with the lifestyles that accompanied them. It’s a story most of us already know in part, although Leonard has made use of extensive research, including newly released FBI files, to produce his ‘new critical history’.

It is a story of non-acceptance and rejection, of protecting financial and power institutions and investments, of racism, media manipulation and censorship. It evidences bewilderment and fear, along with institutional rejection of the idea of free speech, especially when it comes to protesting against war and racial segregation, advocating the use of recreational drugs, or questioning traditional morals and work ethics.

So here is the evidence of who was watching who, of why some performers and acts made it big and others didn’t, of paranoid and fearful responses to change, and a desperation to protect the status quo, the myth of suburban middle class white affluent America. Here are people in power who are afraid of Bob Dylan, of Phil Ochs, of Mississippi Blues and West Coast psychedelia, of Native Americans, Blacks, Asians, sex, sexuality, electric guitars, amplification, long hair and make-up. Or maybe just afraid full stop.

Despite the persecution and surveillance of Nina Simone, Sam Cooke, Johnny Cash, Pete Seeger and assorted folkies, as well as whole swathes of other musicians, there was no stopping the music. If the ‘revolution’ failed it wasn’t because of the FBI or CIA, it was because the counterculture imploded and young people grew up to mostly become what they had never wanted to be: new versions of their parents, part of the problem not the answer. And of course big business bought up the music, neutered it, and quickly learnt how to sell it to us.

Now and Forever is far removed from social revolution, it is a detailed, exhaustive and sometimes exhuasting exploration of ‘the loop’ in music, although it touches upon film and the visual arts too. My main problem with it is that Baumgärtel conflates loops with repetition: I don’t mean to be pedantic but surely loops are analogue and in due course decay and stretch, which is very different from digital sequencers or musicians repeating phrases or sequences?

Whilst he soon asserts that ‘[i]f you repeat the same thing it becomes music’ – which I’d question as a rule or a given anyway, he seems less able to take on board the fact that a repeated thing changes, because it is preceded and followed by itself; that is it changes in the hearing if not the delivery. I’m also not willing to accept that Sam Phillips’ treatment of Elvis Presley’s recordings are to do with loops: an echo is not a loop!

However, when I stop grunting about these issues, the book has some fantastic episodes. I’m especially drawn to his chapters on ‘Pierre Schaeffer and the French musique concrète’, ‘Karlheinz Stockhausen and the Music of the Sound Laboratories’, and the later cluster of material which progresses from ‘La Monte Young, Andy Warhol and the Suspension of Time’ to Terry Riley and then early Steve Reich before considering psychedelia. Unfortunately, having explored Ken Kesey’s anarchic use of sound on the Merry Pranksters bus, we get a somewhat laboured and overbaked chapter about the Beatles, focussing on ‘Tomorrow Never Knows’ and ‘Revolution 9′, along with an explanation of what a mellotron is or was. Whilst the Beatles may well have been influenced by other composers’ use of loops, it’s hard to take their experimental dabblings any more seriously than their Eastern mysticism.

As I’ve said above, much of this book is fascinating stuff, although the use of a repeated film kiss as a starting point is bewildering, as is the conflation of Warhol’s screenprinted grids with audio loops. Along with better editing (I don’t think Baumgärtal’s repetitions of quotes and phrases is deliberate), I’d like to have seen more consideration of contemporary dance music which makes use of repetition, and more about how music can ‘destroy subjectivity’, when we are immersed in it or it is used as a sonic weapon. Maybe the remit of the book is simply too wide? The idea of the suspension of time, the creation of minimal music and use and abuses of technology would fill a book, as would the consideration of music composed in the (pre-digital) sound studio. I guess the ‘Towards’ in the title is a kind of get out clause, and I can’t deny it’s an intriguing and complex history that the author has assembled.

Rupert Loydell