Antonin Artaud (1896-1948) is one of the greatest examples in art of the imaginative retrieval of a life that was beyond repair. What he ultimately accomplished should bear a torch through the dark nights of all our souls. Between 1969 and 1972, Nancy Spero (1926-2009) engaged Artaud’s sufferings and resurrection in the creation of first The Artaud Paintings and then in The Codex Artaud. The Codex is a breakthrough work which enabled her to continually extend her imaginative range over the next three and a half decades. Here I would like to offer my sense of the fulgurating force that Nancy met in taking on Artaud’s writings and drawings, to address the mysterious Sheela-na-gig figures that she included in the 1980s in her pantheon of feminine dynamics, and to conclude with an ode to Nancy in which I celebrate the extraordinary release involved in her body of work.

*

While Artaud cannot be called a shaman, there is a shamanic matrix binding his life and work. This presence contributes significantly to the way his image strikes us. Although there is nothing in Artaud’s materials, to my knowledge, that would indicate that he consciously made use of shamanic lore or stance, such a lack makes the matrix even more pertinent. When I hold up Artaud’s image, I see shamanic elements in it like a black rootwork suspended, coagulated yet unstable, in liquid.

Shamanic quest, initiation, and practice often involve the following: a spiritual crisis as a youth during whichthenovice appears crazed or dead. Such a crisis can lead to a prolonged and excruciating vision quest. To gain access to invisible powers, the novice must undergo a transformation involving suffering, symbolic death and resurrection. In other cases, psychotomimetic plants are ingested as “bridges” to the supernatural world. In a trance state of initiational torture the novice’s body is “dismembered,” sometimes “cooked,” and replaced by a “new body,” with quartz crystals, associated with lightning. One definition of a shaman is that he is one whose body is “stuffed with solidified light.” The novice also learns a new language which he will intone to invoke spirit allies (or dispel spirit enemies) and he often takes on a new name.

Once a shaman, his (or her) work is to maintain the spiritual equilibrium of his community, keeping open communication between the three cosmic zones: earth, sky, and underworld. He facilitates this via the axis mundi, or World Tree, which appears in many guises: ladder, bridge, vine, stairs etc. The long and dangerous excursions to sky and underworld—to retrieve lost souls or to accompany the recently dead—involve rhythmic chanting and drumming. The shaman’s drum, thought of as his horse, carries him to his destination and also helps him drive away demons. During trance, he may speak in tongues, babble, or prophesy in a falsetto voice. He spits and gestures to discharge illnesses and spells attacking his body.

In the case of Artaud, a shamanic pattern, in a somewhat crazy quilt way, is there, from teenage crisis (resulting in several years of rest cures in Swiss clinics), complaints throughout the 1920s of being “separated” or even non-existent, a vision quest to the Mexican Tarahumara Indians (several decades before Carlos Castaneda popularized such journeys), and the use of a magical dagger and cane. After his breakdown in 1937, Artaud identified himself as Antonéo Arlanopoulos, born in Smyrna in 1904. He later claimed to be possessed by doubles or demons (among whom were Astral, Flat-nosed Pliers, Those Born of Sweat, and the Incarnation of Evil, Cigul) who dictated letters in his hand, continually spied on him, and attempted to steal not only his thoughts before he could make them conscious but his semen and excrement. To all of this we must add Artaud’s subjection to a particularly pernicious kind of twentieth-century lightning: electroshock. While in the Rodez asylum, from February 1943 to May 1946, Artaud received fifty-one electroshocks. After one series, while he was in a ninety minute coma, his supervisor, Dr.Gaston Ferdière, decided that he was dead and ordered that his body be dispatched to the asylum mortuary.

“Dismembered” in Bardo comas by battalions of hungry ghosts, he returned, semi-reinvented, with a new language, consisting of nearly incomprehensible sound-syllables and brilliant, if paranoid, arguments. He used the block of wood that Dr. Delmas placed in his room at Ivry-sur-Seine during the final years of his life like a drum. He also had a “bridge” which he wrote was located between his anus and his sex (an area Tantric Buddhism identifies as the Muladhara Chakra, the seat of a novice’s spiritual potential). In his ferocious poem “Artaud the Mômo” he reported that he was murdered on this “bridge” by God who pounced on him in order to sack his poetry. In his 1947 radio poem “To Have Done with the Judgment of God” he envisioned the true human body as one that was organless, all bone and nerve. Such a body remained an unsolvable problem becausethe“lightning” that destroyed “the old Artaud” (burying him in his own toothless gum) did not provide new quartz organs, or chunks of solidified light.

What is devastatingly missing in this shaman scenario is a community. In this regard, Artaud is a Kafka man put through profound and transfiguring rituals while finding out stage by stage that they no longer count. He is a shaman in a nightmare in which all the supporting input from a community that appreciates the shaman’s death and transformation as aspects of its own wholeness is, instead, handed over to mockers who revile the novice at each stage of his initiation.

In spite of this terrible saga, over the last three years of his life Artaud engineered a breakthrough that enabled his cratered psyche to rise into view, smelling of its multiple deaths and proud of its contours, affirmatively ghastly in its power to protect and organize its loathed and beloved cores.

*

Shortly aftert the fifty-first electroshock, in January, 1945, Artaud began to draw with such an all-absorbing intensity that it appeared to Dr. Ferdière that there had been a crucial shift in his patient’s focus from unacceptable misbehavior to a concentration on a creative project, and he ended the electroshocks. What Artaud confronted in working on large sheets of paper with pencils, crayons, and chalk, was his own destruction. In flurries of dismemberment and reconstitution, images of splinters, cancers, torn bodies, penises, insects, spikes and internal organs were projected and realigned. He also began to write in school-children’s notebooks (by the end of his life in March 1948 he had made entries and drawings in four hundred and six notebooks). Drawing and writing began to overlap, with words and phrases often jousting for space with fragments ofthehuman body. At the same time, he began to transfer his humming and chanting into written sound blocks inserted first into letters, later into poems. These “syllable words” were part of his self-defense against demons as well as an aggression against them. The effect of these syllables—some of which are drawn from Greek and Latin words and magical Assyrian texts denoting parts of the body—appears to be to physicalize the writing in a way that contrasts sharply with the veering fantasy and argument of the texts.

Once released from Rodez, and based in a clinic outside of Paris, Artaud turned a derelict pavilion into his workshop. By the end of his life less than two years later the damp, dirty walls of this last “theater” were smeared with blood; his worktable, his pounding stump, and the head of his bed were gouged with knife holes.

Artaud would draw standing before a table, making noises. The sitter was forbidden to move but allowed to talk. Artaud made dots by crushing his pencil lead into the paper; his strokes were so violent that he sometimes tore the paper. Paule Thévenin—Artaud’s dearest friend, sitter, and editor—told Stephen Barber that sitting for Artaud was like being flayed alive.

Glancing back to Artaud’s original Theater of Cruelty vision of the 1920s we can see how faithful he was to this all-embracing project. He compressed its grandiosity into a one-on-one face-to-face combat; the creator-director became a creator-drawer, the spectators a single, targeted sitter. The completed portraits—dappled with moldy and vital flesh, crawling with wiry agitations on the verge of becoming writing, and animated with inner forces that appeared to be redefining the skull—were the sitters’ doubles.

It had taken nearly two decades of rejection, abuse and internal mayhem for Artaud to grasp that the only site at which he could exercise his faculties at large was one where he could completely control the unfolding of an event. His Stations of the Cross, as it were, now look satanically and meaningfully planned. He had tried to project an unrealizable Theater of Cruelty onto a new kind of stage, but it boomeranged at him and imploded. Rather than silencing or totally destroying him, the implosion populated his inner wasteland with saint-quality demons and willy-nilly placed him in the hands of that doctor who fried him alive for nineteen months.

*

I met Nancy and her husband Leon Golub in Bloomington, Indiana in the late 1950s and we became dear friends after becoming reacquainted in NYC in 1967. Nancy, Leon, and their three sons were living at 71st and Broadway and I, having left my wife and son, was living alone Japanese-style on the floor of a basement room in Greenwich Village. Nancy and Leon began inviting me for dinner, and the long evenings of conversation that followed, every couple of weeks, and these invitations made a huge difference in my otherwise turbulent life. Nancy spoke very little about her art but it was clear that she felt very isolated and without any support system, such as a gallery might provide, other than for Leon himself who was always over the decades right there for her. At one point I had a brief misadventure with Scientology and proposed to Nancy that she take a course in Dianetics that might help her hold her own in meetings with gallery people. Of course she declined. She was working on the Bombs and Helicopter series at the time and one evening showed me some of those trenchant gouaches. I was on the verge of starting my literary journal Caterpillar and upon seeing one extraordinary piece (at that time called “The Bomb,” now identified as “Male Bomb”) offered to put it on the cover of my first issue. Nancy was delighted. I think it must have been the first piece of hers to appear on the cover of anything. Leon then wrote an article, “Bombs and Helicopters—The Art of Nancy Spero,” which I published in the same issue.

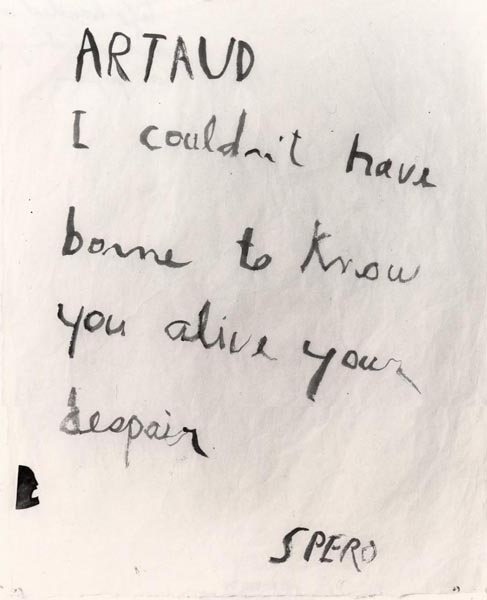

As I recall, Artaud began to make his way into our conversations in 1969 after Nancy read the City Lights Artaud Anthology and shortly before, with my new companion and later wife, Caryl, I left for the west coast. Nancy was bowled over by Artaud’s seething consternation and seemed amazed that a man could suffer as Artaud claimed he did, as if such suffering usually belonged to women. I think that it was this identification in suffering that enabled her to relate to his anger and apocalyptic pronouncements. Although we will probably never know exactly what demons Nancy herself was exorcising in her two Artaud projects, it seems clear to me that especially the latter work was a central rite of passage for her between the early figure-centered paintings and drawings and the post Codex Artaud centrifugally-unfolding scrolls of female bodies in beautiful self-possession.

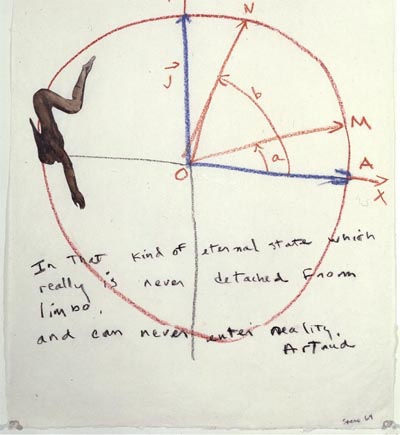

Before commenting on some of her strategies in composing The Codex Artaud, I would like for you to hear (from my translation of Artaud’s writings from his final 1945-1948 period, Watchfiends & Rack Screams) a poem that in its six pages is charged with the kind of anguish and self-reinvention that must have burrowed into Nancy during this critically transitional period of her career. Copies of the first edition of Artaud le Mômo had been in print since 1947, but I do not know if Nancy ever read the work. I do know, on the basis of Artaud’s writing that she included in the Codex, that she had read and responded to Artaud’s letters to the Paris publisher Henri Parisot written from Rodez in 1945/46. Such letters function as a prelude to this poem which was written shortly after Artaud was released from the Rodez asylum and returned to a non-incarcerated life. As Jon Bird has observed: “A composite of delirium and anger, Mômo evokes the unfathomable depths of interiority, of the self at the edge of an abyss that gapes onto the underworld (which is the sexually abjected and grotesque body), and of a death which has to be confronted and embraced in order to find a life forthe creative imagination.” It is one thing to talk about Artaud; it is another to hear him as he proposed himself upon ending his eight years and eight months in asylums.

Here I will translate only the first of the five sections of the poem, “The Return of Artaud, the Mômo,” a bristling declaration that he is back. The word “mômo” is Marseilles slang for simpleton or village idiot. This word may have called forth in Artaud’s mind the Greek god of mockery and raillery, Momus, said by Hesiod to be the son of Sleep and Night, the nocturnal voice of Hermes, bearing a crotalum in contrast to a caduceus.

*

THE RETURN OF ARTAUD, THE MOMO

The anchored spirit,

screwed into me

-by the psychic

lubricious thrust

of the sky

is the one who thinks

every temptation,

every desire,

every inhibition.

o dedi

o dada orzoura

o dou zoura

a dada skizi

o kaya

o kaya pontoura

o pontoura

a pena

poni

It’s the penetral spider veil,

the female on or fur

of either-or the sail,

the anal plate of anayor.

(You lift nothing from it, god,

because it’s me.

You never lifted anything of this order from me.

I’m writing it here for the first time,

I’m finding it for the first time.)

Not the membrane of the chasm,

nor the member omitted from this jism,

issued from a depredation,

but an old bag,

outside membrane,

outside of where it’s hard or soft.

B’now passed through the hard and soft,

spread out this old bag in palm,

pulled, stretched like a palm

of hand

bloodless from keeping rigid,

black, violet

from stretching to soft.

But what then in the end, you, the madman?

Me?

This tongue between four gums,

this meat between two knees,

this piece of hole

for madmen.

Yet precisely not for madmen.

For respectable men,

whom a delirium to belch everywhere planes,

and who from this belch

made the leaf,

listen closely:

made the leaf

of the beginning of generations

in the palmate old bag of my holes,

mine.

Which holes, holes of what?

Of soul, of spirit, of me, and of being;

but in the place where no one gives a shit,

father, mother, Artaud and artoo.

In the humus of the plot with wheels,

in the breathing humus of the plot

of this void,

between hard and soft.

Black, violet,

rigid,

recreant

and that’s all.

Which means that there is a bone,

where

god

sat down on the poet,

in order to sack the ingestion

of his lines

like the head farts

that he wheedles out of him through his cunt,

that he would wheedle out of him from the bottom of the ages,

down to the bottom of his cunt hole,

and it’s not a cunt prank

that he plays on him in this way,

it’s the prank of the whole earth

against whoever has balls

in his cunt.

And if you don’t get the image,

–and that’s what I hear you saying

in a circle,

that you don’t get the image

which is at the bottom

of my cunt hole,

it’s because you don’t know the bottom,

not of things,

but of my cunt,

mine,

although since the bottom of the ages

you’ve all been lapping there in a circle

as if badmouthing an alienage,

plotting an incarceration to death.

ge re ghi

regheghi

geghena

e reghena

a gegha

riri

Between the ass and the shirt,

between the jism and the under-bet,

between the member and the let down,

between the member and the blade,

between the slat and the ceiling,

between the sperm and the explosion,

‘tween the fishbone and ‘tween the slime,

between the ass and everyone’s

seizure

of the high-pressure trap

of an ejaculation death rattle

is neither a point

nor a stone

burst dead at the foot of a bound

but the severed member of a soul

(the soul is no more than an old saw)

but the terrifying suspension

of a breath of alienation

raped, clipped, completely sucked off

by all the insolent riff-raff

of all the turd-buggered

who had no grub

in order to live

than to gobble

Artaud

mômo

there, where one can fuck sooner

than me

and the other get hard higher

than me

in myself

if he has taken care to put his head

on the curvature of that bone

located between anus and sex,

of that hoed bone that I say

in the filth

of a paradise

whose first dupe on earth

was not father nor mother

who diddled you in this den

but

I

screwed into my madness.

And what seized hold of me

that I too rolled my lifethere?

ME,

NOTHING, nothing.

Because I,

I am there,

I’m there

and it is life

that rolls its obscene palm there.

Ok.

And afterward?

Afterward? Afterward?

The old Artaud

is buried

in the chimney hole

he owes to his cold gum

to the day when he was killed!

And afterward?

Afterward?

Afterward!

He is this unframed hole

that life wanted to frame.

Because he is not a hole

but a nose

that always knew all to well to sniff

the wind of the apocalyptic

head

which they suck on his clenched ass,

and that Artaud’s ass is good

for pimps in Miserere.

And you too you have your gum,

your right gum buried,

god,

you too your gum is cold

for an infinity of years

since you sent me your innate ass

to see if I was going to be born

at last

since the time you were waiting for me

while scraping

my absentee belly.

menendi anenbi

embenda

tarch inemptle

o marchti

tarch paiolt

a tinemptle

orch pendui

o patendi

a merchit

orch torpch

ta urchpt orchpt

ta tro taurch

campli

ko ti aunch

a ti aunch

aungbli

*

Artaud’s destruction by God in this poem, which transforms him into an enraged but highly imaginative simpleton, strikes me as much more of an initiatory death and resurrection associated with shamanic consecration than demonic Christian judgment. This initiation also includes the bestowal of a secret language which evokes the“animal language” of shamans worldwide used to communicate with celestial spirits.

While Artaud vituperated against masturbation, the creation of the “Mômo” in the poem is implicitly masturbational, as if this double were issuing from the speaker’s own body. Such recalls the ancient Egyptian theology in which Atum says: “I copulated in my hand, I joined myself to my shadow and spurted out of my own mouth. I spewed forth as Shu and spat forth as Tefnut.”

With an eye to imagery in Codex Artaud now to be discussed, I also note the doubling of tongue and erection in “This tongue between four gums, / this meat between two knees,” and the poet as an androgynous grotesque made to suffer for such wholeness (“it’s the prank of the whole earth / against whoever has balls / in his cunt.”).

*

Christopher Lyon opens his excellent forty-three page chapter on Codex Artaud, in Nancy Spero: The Work (Prestel, 2010) with the following description of the scrolls:

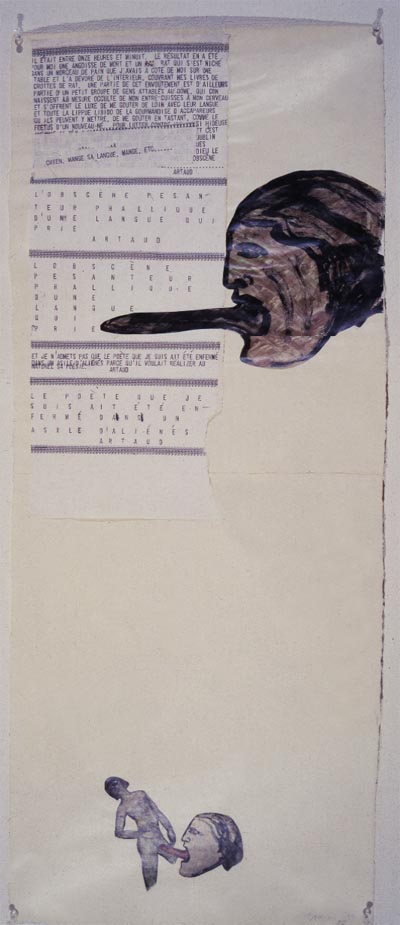

“The Codex Artaud is a series of thirty-seven collages on panels composed of sheets of paper glued end-to-end to form horizontal or vertical strips. The panels are numbered I to XXXIIIc; three are diptychs… The work was made in 1971 and 1972, with with the exception of one panel dated 1973. One image, Codex Artaud IV, is presently unaccounted for. The extended narrow strips of the Codex Artaud were a startling departure from Spero’s previous practice and from conventional formats for paintings and works on paper. “I never thought of my work in terms of being radical,” Spero told an interviewer in 2004, “although I tried to make it radical—that is, to shift the premise of what goes for pictures on a wall. I wanted my work to say something other than the usual—the usual format for an artwork being a rectangle, a square, of anything flat, framed, and attached or hooked onthewall. That was accepted practice, mainline thinking. So I decided to experiment—to extend the square or rectangle that was straight ahead of the viewer and to have something that one would have to look at with peripheral vision engaged…. The works in the series range in size from 18 inches by 4 feet to 25 inches by 25 feet. I gave myself leeway.”

There are two reoccurring motifs in the Codex: As best I can tell, there are around one hundred and forty quotations from Artaud’s writing in French typed out in capital letters on a bulletin typewriter on strips of paper and pasted on the panels. The typing appears to be intentionally slipshod, with some words overlapping, some letters missing. While the quotations are often in short narrow paragraphs, they sometimes veer into one letter per line vertical trails or bunch up in dense, overlapping masses. They are cut through and bordered by straight lines and dense grids composed of a repeated single letter or keyboard symbol. Certain word columns are sheared off so as to be only partially readable. Given the huge amount of blank space in the panels, the word lines, paragraphs, and clusters, some upside down, some atilt and crisscrossing, make me think of being in a prison cell overhearing bits and pieces of conversation at night in an adjacent cell. At the same time, a single speaker is implied, obsessively improvising on his anguish, asserting, in fragmentary bursts, his mistreatment and loathing of authority.

Lyon mentions that Spero’s library included Volumes 1, 4, 8, and 9 of the Gallimard Artaud Oeuvres Complètes. As best I can tell the majority of the quotations come from Volumes 1 and 9, which is to say from Artaud’s early writings around 1924/25 and from his later writings (three quotations are from his superb short essay “Revolt Against Poetry,” written in Rodez in 1944 while he was undergoing electroshock) and 1945 letters to Henri Parisot (one of which includes an extraordinary attempt to discover the fundamental substance of the soul). There are no quotations from Artaud’s famous collection of theater essays, “The Theater and its Double” in Volume 4.

Again, to the best that I can tell, quotes from early and late periods are often found on the same panel. That is, no chronological progression is implied. In fact, according to Samm Kunce, Spero’s studio manager and assistant, Nancy never gave any indication that there was an intended sequence in presenting the Codex’s panels.

The second motif are the cut-out figures, painted with metallic gouache and ink, and fixed, like the quotation strips, to the panels. There appear to be about the same number of figures as quotations. The most common visual motif, of which I count around thirty examples, is a severed head sticking out its tongue, evoking a range of readings: tongue as erection, as knife, as tusk, as snake. In a few cases, thick tongues seem jammed into the heads’ open mouths as if blocking speech, or as stakes driven into the head’s throat. One pasted on quotation from a 1945 letter to Parisot, “The obscene phallic weight of a tongue that prays,” evokes the tongue as penis lines from “The Return of Artaud, the Mômo.” There is also something apotropaic about these tongues as if they are warding off noxious spirits, recalling Artaud’s obsession of being assaulted by doubles. In this context it is also worth considering that in many tribal cultures the head is considered to be the reservoir of the life stuff. As the main storehouse of bone marrow, the brain is believed to be the source of semen, via the spinal cord, and its fertility is assimilated to cosmic fertility of the sun, rain, and lightning. Like the head of the shaman-bard Orpheus cast upon the isle of Lesbos, the head has a continuing life of its own.

The most spectacular figures in Spero’s Codex pantheon are human-headed serpents, sticking out their tongues, rearing like cobras, connected to a single snake body. As I was staring at one of these marvellous grotesques I realized that I had seen its prototype before, so I got out my copy of Knowledge for the Afterlife / The Egyptian Amduat—A Quest for Immortality. The Amduat is a description of the journey of the Sungod through the night world, also the world of the deceased. This journey is divided into twelve hours and the reproductions in my book come from the walls of the tomb of Pharaoh Tuthmosis III (New Kingdom, around 1470 B.C.). In the triple-tiered frieze depicting the Fourth Hour is a triple-headed serpent on a single body with little legs and feet. The description of the text informs us that in the Amduat multi-headed serpents are protector spirits. Spero was apparently familiar with this night journey, for in a 1994 interview with Jo Anna Isaak she mentioned that the title of her work The Hours of the Night came from the Egyptian and referred to the Sungod’s twelve hour passage through the underworld.

In The Codex Artaud, there are also images of Khepri, the renewed form of the Sungod depicted as a scarab; the sacred Udjat eyes (symbolizing balanced consciousness) with a naked human male figure standing between them; six pyramids; and the marvellous androgynous variation on Nut, the Sky Goddess: a headless, arched body with an erection on one underside and four dugs on the other. Facing the erection is an open-mouthed severed head implying simultaneously castration and fellatio.

The Egyptian Amduat presence in the Codex suggests that a parallel journey is taking place there: that of Artaud and Spero, each in their own way, through death and rebirth. Such casts a narrative shadow over the Codex’s otherwise lack of sequence. However, the primary drift of Codex Artaud is one of paratactic surprise. Shorn of context, the Artaud quotations either float about like fragmentary telegrams from Hell, stack up in layered paragraphs evoking partially-destroyed steles, or appear as chunks of ancient walls scored with diagonal word masses simultaneously semi-legible and obscure.

*

In 1987 I wrote Nancy about a book I had discovered, Jørgen Andersen’s The Witch on the Wall, on Irish and English church wall carvings and bas-reliefs of a female figure called Sheela-na-gig. Nancy called me and asked to borrow the book. In another book on this subject, Sheela-na-gigs / Unraveling an Enigma, Barbara Freitag writes: “The common denominator of the Sheela-na-gigs is the frontal representation of a standing, squatting or seated nude female displaying her pudenda. The greatest value was obviously attached to the head and genital area because these two parts are strongly modeled and represented disproportionately large compared to the rest of the figure. But whereas the vulva looks big and plump, giving the impression of fertility, the head and chest look bony and emaciated, suggesting old age.”

From 1981 to 2000, I edited a literary and arts journal I founded called Sulfur. In 1990, Nancy sent me a reproduction of a hand-printed collage on paper called “Sheela and Wilma,” which we wrapped around the back, spine, and cover of Sulfur #28 as the cover art. These two female figures are juxtaposed one after the other in a kind of chorus line.

I have never been able to find out any information on the Wilma figure, but I am pretty sure she is from prehistoric Australian rock art. She appears to have two schematic children in her sketchy oval belly. We can think of her as Nancy’s Rockette.

Besides Nancy’s “Sheela and Wilma” collage there is also a collage of linked Sheelas called “Chorus Line,” individual prints of different Sheelas (one of which she sent Caryl and me as a gift), cut and pasted printed panels called “Sheela and Dancing Figures,” and a free-standing sculpture called “Coffee Table Sheela.” I found Barbara Freitag’s book on the Sheela-na-gigs especially interesting and assembled some of its information into a collage which I dedicated to Nancy.

Sheela-na-gig

Medieval European motherhood hazards: on the average, death at 27. Most of her adult years she was pregnant, or nursing. She buried one-third of her children before they reached maturity. Dublin, late-19th century: one mother in every seven had ten or more children baptized. Over twenty-two percent of these infants died in their first twelve months. Poor nutrition; inadequate protein, insufficient iron.

Who could she turn to? Not the Church. “God the Father, the Son, and the Holy Ghost have ordered that you bring forth your child with pain and bring it up with sorrow and distress and many sleepless nights.”

Thus pagan cures and charms: Artemisia placed on the genitalia to speed birth. Stones were pulverized and drunk, crushed then mixed with red sandalwood, citron wax, cypress cones. Skin of a white worm worn around her waist.

Midwives would smear their hands with butter or hog’s grease, then work on her vulva, pulling, widening the birth passage to help the baby glide out.

Thus folk deities, Spiritus familiars. Thus Sheela, with grotesque lower abdomen, cavernous oval-shaped vulva, held open, so big as to reach the ground.

Sheela’s genital areas were rubbed (like the yonis of Hindu goddesses).

Birthing stones may have been placed in their genitalia.

Sheelas were drilled, head and body, with holes,

portrayed in vertical birth-giving posture.

Some were depicted with birth girdles, or holding birthing stones.

Some have protruding amniotic sacs,

or vertical channels cut below the vulva,

egg-shaped objects lying between their open legs—

hanging between the open legs of the Romsey Sheela:

a baby’s head with eyes, nose, and mouth.

Yet these Sheelas are also breastless, with skeletal rib cages, skull-like heads,

hollow eyes. They are found surrounded by graveyards, located near the Lich Gate.

Sheela is not only the defender of the door but is to be repelled there. A “bald grand-

Mother,” she traces back to Mistress of the Animals.

At Binsteed, Sheela sits on an animal head.

At Whittlesford Church, she is approached by a crouching ithyphallic beast.

By the holy well of Melshach,

garments fastened up under their arms

hands joined, women are dancing in a circle.

In their midst: a crone, dipping a vessel into the water,

sprinkling the dancers.

*

Several years ago, reflecting on Nancy Spero’s Artaud projects as catalysts for her images of feminine release including Greek dildo dancers as well as Sheela-na-gigs, I wrote an “Ode” to the defiance and joy in her feminine release. The word “Bowlahoola” in the poem comes from William Blake: it is a rather humorous word for the bowels. With the women’s liberation movement in mind, I refer to Sheela-na-gig as Ms. Gig.

Ode

Daughters Nancy Spero mined through Artaud, plunging

into his Bowlahoola the seminal muscle of her tongue

to release these pater-encrusted Rahabs,

to let them strips and restrip

—from pedestal to Golden Lotus—

the binocular manacles from their feet,

to let them ungag their cunts,

to let their cunts stick out their tongues,

to let them dance inside out the accordion akimbo kick,

the dildo trot, the serpentine waver prance,

Ms. Gig and her wriggling tricksters

rotating through the monument blockage, rooted and free.

Text: Clayton Eshleman (A talk given in London to coincide with the Nancy Spero exhibition at the Serpentine Gallery in 2011)

Art: Nancy Spero

Thanks to Samm Kunce and the Golubs.

“Shortly aftert the fifty-first electroshock, in January, 1945, Artaud began to draw with such an all-absorbing intensity that it appeared to Dr. Ferdière that there had been a crucial shift in his patient’s focus from unacceptable misbehavior to a concentration on a creative project, and he ended the electroshocks”

Perhaps this suggests that, rather than being the terrible torture Clayton suggests, the ECT actually worked for Artaud and helped restore him to some kind of productive creativity?

Comment by sign in stranger on 15 July, 2012 at 3:57 pmAccording to what I have been able to find out concerning Artaud’s positiion on this matter, he began to draw hoping that by doing so, by busying himself in some creative activity that would appear acceptable to Ferdiere, the electro shocks would be stopped. Your interpretation of course is that of Ferdiere’s who immediately took credit for Artaud’s “regeneration.” Artaud himself detested Ferdiere. In one of Stephen Barber’s fine books on Artaud, BLOWS AND BOMBS (Faber & Faber, 1993), Barber writes: “It was in January 1945 that Artaud’s creative capacities came back to him with great strength, and he never stopped working from then until his death three years later. The final work threw out images and writing with ferocious force. For Ferdiere, this return to work was the result of the treatments he had applied, including the electroshocks–without these treatments, the final phase of Artaud’s work would simply not exist. This is extremely unlikely. Artaud had declared in the 1930s that he could only work through the absence of opium; now, he started to work from the time when the electroshocks were absent from his life. The war was coming to a close, and Paris had been liberated from the German Occupation on 23 August 1944. Artaud was slowly able to re-establish contact with his friends there. He also formed a strong friendship with a young doctor who came to work at Rodez in February 1945, Jean Dequeker. Dequeker gave Artaud great encouragement, and supported his violent creative resurgence. He understood Artaud’s need to battle physically against the forces he believed were oppressing him. In opposition to Ferdiere, Dequeker approved of the humming and chanting exercises which Artaud was developing to fortify his new language and images.”

Comment by Clayton Eshleman on 16 July, 2012 at 12:03 pm