by Jan Herman

Q & A: Colin Asher Talks About His New Literary Biography

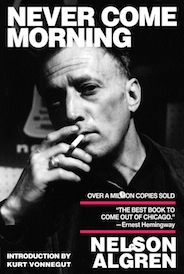

In his introduction to NEVER A LOVELY SO REAL: The Life and Work of Nelson Algren, Colin Asher begins with “the first thing you should know.” He doesn’t offer some piquant biographical detail or some emblematic anecdote to grab our interest which, rest assured, he is thoroughly capable of doing. He informs us without making a fuss that Algren “wrote like this”:

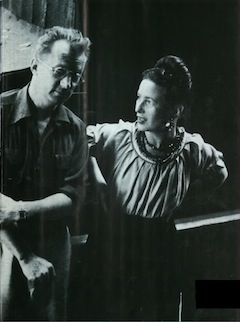

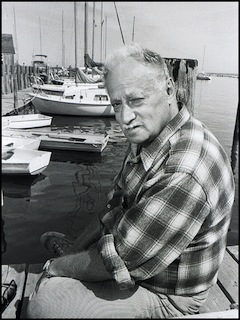

(© Stephen Deutch, early 1960s)

Click to enlarge.

( W.W. Norton & Company, 2019)

Pub. date: April 16, 2019

The captain never drank. Yet, toward nightfall in that smoke-colored season between Indian summer and December’s first true snow, he would sometimes feel half drunken. He would hang his coat neatly over the back of his chair in the leaden station-house twilight, say he was beat from lack of sleep and lay his head across his arms upon the query-room desk.

Yet it wasn’t work that wearied him so and his sleep was harassed by more than a smoke-colored rain. The city had filled him with the guilt of others: he was numbed by his charge sheet’s accusations. For twenty years, upon the same scarred desk, he had been recording larceny and arson, sodomy and simony, boosting, hijacking and shootings in sudden affray: blackmail and terrorism, incest and pauperism, embezzlement and horse theft, tampering and procuring, abduction and quackery, adultery and mackery. Till the finger of guilt, pointed so sternly for so long across the query-room blotter, had grown bored with it all at last and turned, capriciously, to touch the fibers of the dark gray muscle behind the captain’s light gray eyes.

Click to see 2002 edition, o.p.

Doubleday & Co., Inc.

the Golden Arm

Seven Stories Press, 1999

Those are the opening paragraphs of The Man With the Golden Arm, the 1949 novel that made Algren famous before he dwindled into cult status. The captain is the same one who appears earlier in “The Captain Has Bad Dreams,” a short story in The Neon Wilderness; he’s the same weary captain who now eyes the same smalltime hustlers in the same Chicago police station—only this time lined up in front of him is Frankie Machine, a sharp-tongued “smashnosed vet” with “buffalo-colored eyes,” home from war with a Purple Heart and “shrapnel buried in his liver for keeps.” We learn soon enough that Frankie Machine is known as Dealer, a professional poker player who deals the hands in a crooked game run by the neighborhood crime boss. Machine is also an alcoholic junkie. Standing beside him is a “wayward 4-F” with “tortoise-shelled glasses separating the outthrust ears” and a “cockiness which association with Frankie had lent him.” His name is Sparrow. Both are central characters in Arm. Neither are the kind of people you will meet in Bellow’s Chicago.

I came to know Colin because of our mutual interest in Algren. Ever since he embarked on Never a Lovely So Real, I believed it would be the definitive biography. When he began his research, I had such confidence in the project that I gave him all my Algren files, including transcripts of my recorded interviews of Algren’s friends and associates, some going back to the 1930s, his two ex-wives, and others who connected with him. I had become a friend of Algren’s myself, late in his life. I wrote about him. I was there when he died, on May 9, 1981, in a little house on Long Island. Afterward, four of his most devoted friends—Studs Terkel, Stephen Deutch, Candida Donadio, and Kay Boyle—urged me to do a biography. But I never got beyond the research stage, and it makes me really happy that Colin Asher did. In straightforward yet graceful prose and with deep insight—let alone an immense amount of meticulous research—he has produced a major literary biography. Never a Lovely So Real testifies to the richness of Algren’s genius as a writer and explains the misunderstood nature of the man. It reveals what made him tick, exposes the legends, and brings him to life in a way no previous biography has. It certainly changed my own perception of him. And if there’s any justice, it will put Algren’s books back at the heart of the 20th-century American canon.

J.H.: Let’s start with your title — ‘Never A Lovely So Real’ — it’s unusual. Everybody I’ve mentioned it to loves it. How did you decide on it?

Doubleday & Co., Inc

University of Chicago Press

C.A.: As you know, the title comes from a line in Algren’s prose poem, Chicago: City on the Make. I first heard Algren’s name when my mother quoted a bit of the book to me over the phone. It was 2009, and I was complaining about the state of American literature, how disinterested it seemed in reckoning with the Great Recession, and my mother said, in essence, You should read Algren. He had that great line about loving a woman with a broken nose.

She couldn’t remember which book the line came from, so it took me a while to find it. I think City on the Make was about the third Algren book I read, but when I came across the passage she had referenced, I remembered her comment, flagged the relevant page, and underlined the following:

Yet once you’ve come to be part of this particular patch, you’ll never love another. Like loving a woman with a broken nose, you may well find lovelier lovelies. But never a lovely so real.

At first, I loved those lines for the sentiment they express—that our imperfections are often the well spring of our virtues. Then, as I got to know Algren’s work better, I saw them as a beautiful encapsulation of his attitude toward his characters. That’s why, when I penned an essay about Algren for The Believer, way back in 2013, I called my piece: “But Never a Lovely so Real.” The more deeply I grew to know Algren, the more resonant the phrase seemed. Eventually, I realized that it both describes Algren’s attitude toward his characters, and the tension that exists between his personal flaws and his immense talent. After I understood that, there was never any serious question of the book having a different title. Carl Sandburg once wrote a beautiful line about Algren’s characters. He said that they all have a “strange midnight dignity.” For a few months, I considered using that line as a title—but it just wasn’t as resonant as Never a Lovely so Real.

J.H.: Yours will be the third biography of Algren. Most writers are lucky (or unlucky) to get one. Why do you think there has been so much interest in his life?

C.A.: The simplest answer is also the truest: Algren’s life remains interesting because of his work.

Algren’s writing has several things going against it. He uses vernacular extensively, which can be difficult to parse now that it is decades old. His books are lightly plotted, and his protagonists are deeply flawed. The environments he conjures are brutal. And yet, Algren’s books have aged well. One reason for that is the singularity of his prose. It’s possible to orient Algren’s work within the American tradition—his stuff contains some of the naturalism in Farrell and early Steinbeck; he writes with a rhythm that’s reminiscent of Hemingway, occasionally; and he uses imagery that has echoes of Carl Sandburg’s poems—but he was not derivative; as a stylist, he stood alone. He consciously tried to appeal to the eye and the ear simultaneously, and as a result his work is complex, closely observed and precise, but also propulsive and pleasurable to read.

‘Because of the singularity of Algren’s style, people still feel they’ve discovered something new when they first encounter his work.’

A brief anecdote: I recently introduced an acquaintance to Algren. Trying not to say too much or sell too hard, I suggested she read The Man with the Golden Arm. When I saw her the following week, she enthused: “The book reads like poetry. The sentences have a rhythm. I can hear the rhythm of the El tracks in everything.”

Because of the singularity of Algren’s style, people still feel they’ve discovered something new when they first encounter his work. I had that experience with his writing, and I have heard the same from many people since. Given that Algren wrote his best work more than sixty years ago, and millions of copies of his books have been purchased, this is a remarkable phenomenon, and goes a long way toward explaining why people remain interested in his life.

But Algren’s subject matter is also a factor in his enduring relevance. It’s a cliché to say that a writer whose career peaked and then faded suffered because he was ahead of his time, but in Algren’s case it’s true.

(Photo © Art Shay,)

Algren focused almost exclusively on the lives of people who, he felt, had been marginalized or discarded by America—prisoners, itinerant laborers, alcoholics, morphine addicts, petty criminals, prostitutes, and boxers. Other writers, of course, have done the same. But Algren’s work is distinct because of the convictions that motivated it. He chose his characters advisedly, and saw their stories as an integral part of the American story. He focused on the portions of society that benefit least from America’s wealth because he believed the quality of their lives was an accurate gauge of the country’s moral health, that the struggles they faced foretold the challenges the remainder of society would soon face. This insight allowed him to produce insights that were decades ahead of their time.

Algren served in World War II, and when he returned to the states, he discovered that the country was ascendant, empowered, and feeling self-satisfied. But he was unmoved by the allure of the country’s new-found wealth. Observing America shortly after his return from Europe, Algren saw clearly the psychic damage the country’s focus on material possessions would wreak. He wrote:

Never has any people possessed such a superfluity of physical luxuries accompanied by such a dearth of emotional necessities. In no other country is such great wealth, acquired so purposefully, put to such small purpose. Never has any people driven itself so resolutely toward such diverse goals, to derive so little satisfaction from attainment of any.

Algren also understood that the story America had begun telling about itself—a fairy tale set in the white suburbs, featuring a nuclear family, empowered by the fact that they were residents of the world’s most powerful country—was an exclusive one, and that its stability depended on society’s ability to marginalize or imprison nonconformists. Writing decades before mass incarceration was part of the public discourse, Algren saw it on the horizon.

Incarceration is no longer the burden it was intended to be, he wrote, because— “time off for good conduct means little to men with no place to go and nothing in particular to do when they get there.” Prisons and jails, he reported, are not filled with dangerous people, they are packed with “men and youths who had never picked up any sort of craft—though most of them could learn anything requiring a mechanical turn with ease. It wasn’t so much a lack of aptitude as simply the feeling that no work had any point to it.”

‘Algren focused almost exclusively on the lives of people who, he felt, had been marginalized or discarded by America.’

And for those Americans who chose not to conform but managed to avoid being incarcerated, Algren foresaw a different kind of escape. Much like today, there was an opioid epidemic after the war, and Algren interpreted the drug’s rise as a symptom of society’s moral decay, not a failing on the part of users. He referred to morphine addiction as “the American disease,” and suggested it was a reasonable response to a society so focused on conformity. He wrote:

The addict’s revolt has a special grace. When he shoves a needle into his vein it is, in a sense, to spare others. Somebody had to be punished all right—and he’s the first who’s got it coming. Things are going wrong in the world, so, in a suicidal sort of truculence, he impales himself.

During Algren’s heyday (1942-1956, roughly), these ideas placed him well outside the mainstream of popular discourse. But no longer. Now, his work seems prophetic.

J.H.: How is your biography different from the other Algren biographies?

C.A.: The first full-length Algren biography was written by Bettina Drew, and appeared in 1989. To be clear, I have never been in touch with Drew, but I respect her book and, especially, her research. She was a marvel at tracking people down and getting them to talk, and she created a wonderful archive of her work. However, her efforts were complicated, from inception to release, by factors beyond her control.

Timing was the most significant. Drew began working on her book after Algren’s death, so she could not interview him. But she was also writing before most of Algren’s contemporaries donated their correspondence to archives, and before good biographies of his friends began to appear. She was also working before the Internet made it possible to easily access government files, such as Census, birth, and death records, and before the federal government was ready to release the entirety of Algren’s FBI file.

Inevitably, there were holes in Drew’s research and therefore her book—and everything that has been published since—has, basically, followed the template she created. Being honest, I thought my book would as well. When I signed my contract with Norton and began my research, I imagined I would be writing a short book. I thought I would stick to Drew’s outline, patching holes in it where necessary with ancillary research, and that my major contribution would be a reevaluation of Algren’s written works.

‘I decided to undertake a complete review—or the most complete review I could manage—of Algren’s correspondence and other archival material.’

But early on, I realized that I had to scrap that plan. Within months, I spotted several errors in the previously established record of Algren’s life that made me question whether the remainder could be trusted, and how far. Some of these errors were minor and interesting, I suspect, only to Algren’s fans. But others had more serious implications, and suggested that Algren’s character had, up until that point, been misrepresented.

G.P. Putnam Son’s, Inc.

For instance, early in my research I came across a letter that Algren wrote to a close friend named Roger Groening. In that letter, Algren discusses spending some time with a writer named Robert Gover. Gover was, at the point described in the letter, a young writer who had just made a name for himself with a book called Hundred Dollar Misunderstanding. This was in the mid-1960s, and Algren was already an elder statesman in the literary world. In his letter, Algren explains that he stayed with Gover for a few days while in New York to promote his book Notes From a Sea Diary: Hemingway All the Way, and that his visit nearly ended in violence. Gover, by Algren’s account, asked Algren to read an unpublished manuscript he had been working on. Algren did so, and, by his own account, savaged it in such brutal terms that Gover became livid, and told Algren to leave. Gover’s eyes, Algren wrote to Groening, “when he took his [manuscript] back, were ice green.”

In his letter, Algren seems to brag about treating Gover poorly. There’s a bit of swagger in his telling of the story, which makes it uncomfortable to read, but for some reason, the anecdote didn’t sit well with me. It just didn’t sound right, so I decided to track Gover down and ask him for his side of the story. Drew mentioned the conflict with Gover in her book, briefly, but from the text it was unclear whether she had spoken to Gover or relied on the letter.

It took a little doing, but I found Gover near the end of 2013, retired and writing little, but happy to talk. I expected our conversation to be tense because I was planning to bring up a long-forgotten insult, but I was wrong. As it turned out, Gover had fond memories of Algren. He told me that Algren was a wonderful houseguest, and that they enjoyed each other’s company. I read Algren’s letter to Gover while we were on the phone, and he was shocked. He said no such thing had happened, and proceeded to tell me, in great detail, about his time with Algren. He said they stayed up late together, drinking, and trading stories. Algren, by Gover’s account, was kind and encouraging, and advised Gover not to allow publishers to take advantage of him. In the following years, they crossed paths at a pair of writers’ conferences, and chose to have dinner together several times.

The conversation left me feeling unsteady. I had assumed that I would discover, during the course of my research, that Algren, like everyone, exaggerated or embellished occasionally. But I had, without realizing I had done so, also been assuming that those embellishments would be self-aggrandizing. It had never occurred to me that the man would lie to his friends to make himself seem petty and nasty. And once I had caught him doing so, I began to wonder how often he had done it, and what the collective effect of those embellishments had been on his public image.

So, I decided to undertake a complete review—or the most complete review I could manage—of Algren’s correspondence and other archival material. I retrieved Algren’s letters, transcripts of his speeches, and correspondence mentioning him, from more than fifty archives, most of which had not been created when Drew wrote her book. I also reviewed Drew’s archive, which includes recordings of the interviews she conducted, as well as her notes, rough drafts, and official records, such as Algren’s high school report card. Of that material, the recordings were the most important. Reviewing her interviews, a quarter century after she conducted them, with more material available for corroboration or refutation, I drew some very different conclusions about Algren’s character than she did.

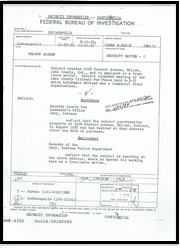

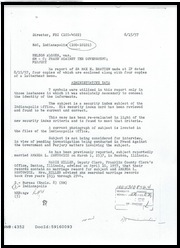

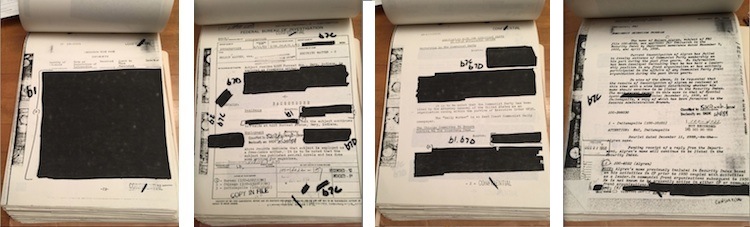

J.H.: Tell me about the FBI’s Algren files that you got hold of. You found more than anyone did. After Nelson died, in 1981, I requested the files and I believe I was the first to get them, although it took years. The main file came from the FBI field office in Washington D.C. Others came from field offices in Chicago; New York; Los Angeles; Springfield, Ill.; Milwaukee, Wisc.; Indianapolis, Ind. — basically wherever information had been collected on him through surveillance, mail cover, questioning of neighbors and associates, through published reports of his activities and secret informants who denounced him as a Communist or a suspected Communist. But when the files arrived after all the waiting, it was a huge letdown. I received 375 pages, but they were so heavily redacted (notwithstanding exceptions / like / these) that I couldn’t do much with them. When I showed them to you, you saw how frustrating and useless they were.

The fourth page is dated 1958. Click to enlarge.

C.A.: The FBI’s files turned out to be important. The fact that the FBI was interested in Algren was first reported by Herbert Mitgang in Dangerous Dossiers (Dutton, 1988). In that book, he reports that he requested Algren’s FBI file, and that the FBI sent him “461 censored pages.” An appeal resulted in an additional 30 pages of material. Drew also requested Algren’s FBI file, and received an identical (I believe) version. Everything written about the FBI’s interest in Algren since then has relied on an FBI file of approximately the same length. The file in question is not quite useless, but it’s so redacted that it nearly is. As a result, there has always been some question about whether Algren’s decline should be attributed to his personal failings or the government’s involvement in his life. When asked, Algren’s friends tended to say that Algren stopped writing because he had writer’s block. Others said Algren wasted his talent drinking, or gambling.

When I began my book, I decided to see if a fresh request for Algren’s FBI file would turn up a more complete version, one that would offer a more satisfying explanation for the premature end of Algren’s career. So, I contacted the National Archives, made the request, learned that securing a copy would set me back about a thousand dollars, and decided to roll the dice. I’m glad I did. The file I received in response was 886 pages long and very lightly redacted. Using it, as well as some ancillary material about the government’s interest in Algren, I was able to make a persuasive case that Algren’s career ended as a result of the FBI’s scrutiny of his life, and the Congress’s interest in his political affiliations. Others have suggested as much in the past, but I’m hoping that my book will settle the question for good and, consequently, reframe the story of Algren’s career.

J.H: In a recent edition of the New York Times Book Review, Kevin Powers writes about “Vonnegut’s unmatched moral clarity.” He says that Kurt Vonnegut, “more than any other writer I can think of, could cut through cant and sophistry and dissembling to expose our collective self-deceptions for what they are.” It makes me wonder whether Powers ever read Algren. Vonnegut himself admired Algren’s work so much that he once called him the better writer. What would you say about Algren’s “moral clarity”?

C.A.: I don’t want to take anything away from Powers or Vonnegut (whose moral clarity I also admire), but I’m happy to discuss the ideas that guided Algren’s work.

Algren had unique beliefs about the role literature should play in society, and about an author’s obligations to their craft. And he wrote about them at length. He believed that the purpose of literature is to challenge authority, and he looked down on any authors who used their writing primarily for self-promotion or declined to write honestly and critically about the times they were living through.

First published in 1942

Avon, 1950

As I mentioned earlier, his decision to write primarily about people who existed on the margins of mainstream society grew out of this conviction, a fact he made clear repeatedly in his writings and speeches. For instance, he once explained that he wrote his second novel, Never Come Morning, because he believed: We can’t understand what’s “happening to ourselves” unless we understand what is happening to the people who share “all the horrors but none of the privileges of our civilization.”

While writing Never a Lovely so Real, I regularly revisited some of Algren’s statements about the purpose of his work as a way of grounding my thinking about his writing. Of course, I made my own judgments about whether or not a particular piece was successful, but I wanted to be sure that I kept his intentions at the front of my mind, that I dwelled, as he did, on the purpose of his work.

The line above was one that I kept at hand while I wrote, and so was a selection from The Man with the Golden Arm. One of that novel’s most famous bits of dialog is spoken by a defrocked priest who proclaims: “We are all members of one another.” That line is repeated several times, and informs the narrative throughout because it plagues the conscience of a character who understands he has fallen short of the priest’s injunction. The line is an allusion to Paul the Apostle’s instruction that “we, though many, form one body, and each member belongs to all the others,” and I have come to think of it as the most concise, and maybe the clearest, articulation of Algren’s ethos. I believe that Algren intended his work to play the same role as the priest’s statement serves in his novel—he wanted his books to deliver the message that we are all bound by our common humanity, and he wanted them to plague the conscience of anyone who tried to exclude some group from the “one body” because of their class, their race, their gender, or a failure to conform.

J.H.: Bettina Drew’s biography was titled “A Life on the Wild Side.” It’s a witty title, but was it more mythification than clarification? How wild was Algren’s life, really?

Algren wasn’t a tame character and he didn’t lead a cosseted life so, in that sense, you could say he was wild. He graduated from college in 1931, the depths of the Great Depression, and shortly afterward, his parents lost their business (a tire shop), their savings, and their home. The family needed money, but Algren was unable to find work in Chicago, so he went on the road to search for a job.

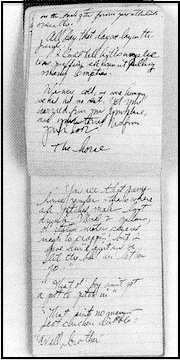

Click to read.

For the next several years—the summer of 1931 to the spring of 1934, roughly—Algren wandered. He travelled north, into Minnesota, then south to New Orleans. He had to flee that city after an acquaintance he was living with was severely beaten, and he ended up in Texas. Eventually, he made his way home and began writing, then he went back on the road—traveling to New York, and then south again. Some accounts romanticize this period of Algren’s life, suggesting that it was a grand adventure. He was guilty of this himself. Later in his life, he penned accounts of these years that are sarcastic and whimsical—absurdist, even. But the truth is, this was a bleak and desperate time for Algren. He traveled by hopping freight trains, hitchhiking, or walking for long distances. He slept outside, or in Rescue Missions, and he ate little. He witnessed violence on the part of the police and his fellow vagabonds, and he was arrested several times, for vagrancy, and theft. He feared for his life regularly, with good reason, and eventually he lost faith in both his ability to support himself, and the American Dream. At the end of this period, he decided that America was “uncivilized.”

‘All day that day we lay in the Jungle … We were cold, we were hungry. We had no rest.’ — Algren’s notebook

Later in his life, Algren had other experiences that could be called wild. He fought in World War II, traveled throughout Europe and into Africa with Simone de Beauvoir, and went to Vietnam to report on the war when he was nearly sixty-years-old.

But when people say Algren led a “wild” life, I don’t think they’re referring to the events I’ve just mentioned. I have noticed a tendency to conflate Algren with his characters, and a presumption that he wrote from experience—that, because he once wrote a novel about teenage petty criminals, he must have been one himself; that, because he knew so much about morphine addiction, he must have been a user himself; that, because so many of his characters drink heavily and party, he must have been a partier and a drinker himself.

Photo © by Art Shay

I understand this conflation—after all, much of American literary fiction is autobiographical, and Algren often spoke about the need to write from experience. But in Algren’s case it is a mistake. He did write from experience, but not his own. He researched his novels the way creative nonfiction writers research their works today, by immersing himself in an environment, taking notes, and asking questions. He spent much time in chaotic and disorganized environments, but his personal habits were abstentious, even Stoic.

According to both of Algren’s wives, he refused all medications—even aspirin—and liked to claim he had never been ill (this is false). He worked out regularly, and for years, he refused to allow alcohol into his house, unless he was entertaining. During Algren’s most productive period, his personal restraint was even more pronounced. Ken McCormick, Algren’s editor at Doubleday, recalled, in an oral history, that Algren kept his telephone in a drawer while he was writing The Man with the Golden Arm, wrapped in a blanket so he couldn’t hear it ring. And in his letters from those years, Algren often mentions going out of his way to avoid friends so that he can write. People who knew him then uniformly describe him as quiet, diffident, serious, and disciplined. He did drink to excess a few times during this period, but they were the exception.

They married and divorced twice.

In truth, on a day-to-day basis, Algren’s life was very tame. He read constantly, and he read everything. He maintained an active correspondence with writers, critics, and friends, created art, and thought of his home as a sanctuary. He referred to one of his apartments as a “nest,” and he said that the only way he could write a good book was to dig in and hide from the world, like a “mole.” Later in his life, Algren did get a bit wilder. As he wrote less, he partied more. In his twenties, he associated with a group of petty criminals, primarily as a means of gathering material. They scorned him at the time, sometimes mocking him publicly because they saw him as a pretender. But as he aged and became embittered by the way the publishing industry and the government had treated him, he drew closer to these folks and adopted some of their habits—drinking more, playing poker more often, and engaging in petty graft. But even during this period he wasn’t a truly wild character.

One fact that always reinforces this for me: When Algren left Chicago in the early 1970s, he sold most of his belongings, but not his books, collages, or pictures. He packed those and paid to have them shipped to New Jersey. It took 75 boxes to do so. That was Algren, a man whose life was defined by literature and art, and who preferred to spend his days reading, discussing what he had been reading, or writing.

J.H.: When I asked Nelson what he thought his best book was, he said it was “A Walk on the Wild Side.” I know he said different things at different times to different people. But that’s what he told me without hesitation, even as he remarked that maybe you do your best work by accident and don’t know it’s your best when you do it. He didn’t always feel so good about “Walk.” I believe, as you do, that “Arm” is his masterpiece. But “Walk” is such an entertaining read, and such a meaningful one, that IMHO it’s another masterpiece—just a different kind. Yet its reception by the poobah crickets when it came out in ’56 was so nasty that it helped put the kabosh on Algren’s career. The novelist Russell Banks, an Algren fan who knew him, has chalked that reception up to “the ‘kill the messenger’ syndrome” for bringing bad news. Or as another formidable novelist, Richard Flanagan, has said, it “made a mockery of the American dream” as “an exposé of the nation’s contempt for its own people.” What’s your take?

Farrar Strauss

Farrar Strauss

Cannongate

C.A.: I feel much divided about A Walk on the Wild Side. This may be a problem particular to my situation, but I have a hard time separating the text from my knowledge of the events leading up to and surrounding its creation.

Algren never wanted to write A Walk on the Wild Side, and in many ways, it is, first and foremost, a product of the Red Scare. Algren sold his first four books before he wrote them—the fourth being The Man with the Golden Arm, a huge commercial and critical success. He believed that his artist freedom was guaranteed after that book’s rapturous reception, and his receipt of the National Book Award. He was wrong. Arm’s release coincided with an increase in the intensity of the Red Scare, and Algren’s new fame brought scrutiny that damaged his career, not freedom. He and the photographer Art Shay signed a contract to release a book of photos and text shortly after Armwas released, but its publication was cancelled for reasons that have never been clear. Algren’s next book, Chicago: City on the Make, began as a magazine article, and his publisher didn’t offer him a contract until the text was finalized—a first for Algren. Next, Algren signed a contract to write a book about the politics of authorship, but after receiving the book’s manuscript, his publisher backed out. The book was eventually released as Nonconformity, but not until long after Algren’s death.

Seven Stories Press

Algren slipped into a depressive fugue around this time, and began acting irresponsibly. He had been saving money for years so that he would not be beholden to his publisher, but after Nonconformity was suppressed, he gambled his savings away—one of the only times he acted so irresponsibly. Afterward, he approached his publisher and asked for an advance to write a fourth novel, but they turned him down—a remarkable event, given that he was one of the country’s most famous authors. Instead, they offered him a small stipend to revise his first novel, Somebody in Boots, for release as a pulp paperback.

That is the genesis of A Walk on the Wild Side. Algren accepted the contract because he was broke, but after he did so, he decided Somebody in Boots was not worth revisiting, and decided to use its framework to write a new novel. It was a decision that almost destroyed his creative drive. For a moment, just after he began writing Wild Side, Algren considered running away from his creative life altogether, and becoming a professional card dealer.

Vanguard Press

Lg Publishing

He gave that idea up, eventually, and went on the road to work on his novel. He retraced a portion of the path he travelled while writing Somebody in Boots—to New Orleans and Texas, then into Mexico—and returned home even more dispirited. He was (justifiably) angry about the way his publisher and the government had treated him, and enraged by the conformity, shallowness, viciousness, and false piety of 1950s America—and that anger informs every word of the text he eventually composed.

You mention Flanagan and Banks. Both are astute readers, and I think it’s telling that they used similar language to describe A Walk on the Wild Side—Banks say the book delivers “news,” Flanagan calls it an “exposé.” They’re both right. Algren’s purpose in writing that book was to broadcast an account of the country’s failings—a goal that is in sharp contrast to that of the books that preceded it.

Photo © Roswitha Hecke

The Man with the Golden Arm is a hopeful lament, a plea for the country to begin paying attention to the health of its soul, and for people to heal themselves by recognizing the humanity of their fellows. The book’s purpose is most evident in its characters’ voices, their existential preoccupations. As I mentioned earlier, a defrocked priest proclaims “we are all members of one another,” and the implications of his pronouncement plague a police Captain who knows he has not lived up to the injunction. Frankie Machine is troubled by the feeling that he’s adrift in the world, rootless and wasting away. “You know who I am?” He asks. “You know who you are? You know who anybody is anymore? And Sparrow, Frankie’s sidekick, laments society’s atomization, and individualism. “Ain’t nobody on anybody’s side no more,” he says. “You’re the oney one on your side ‘n I’m the oney one on mine.”

But Wild Side, published seven years later, is a different creature entirely—it is an announcement that we have gone so far down the road to perdition that we can’t turn back. This too is most evident in the words Algren gifts his characters. The novel’s protagonist, Dove Linkhorn, has little inner life, and stumbles about, being taken advantage of and abused. He’s an innocent, and because he is, everyone he encounters tries to explain the world to him. They dispense advice and warnings freely, and their pronouncements are uniformly dark, and sociopathic.

Dove’s father, a street preacher, leaves an impression early in the book’s narrative when he mounts the steps of a courthouse, drunk on something he calls “Kill-Devil,” and proclaims the end of days. “Un-utter-uble sorrows is in store for all,” he screams. “Invasion by a army! A army of lepers! Two hundred million of flame-throwen cavalry! A river of blood and burnen flesh a hundred mile long!”

“Everybody got to eat,” a character later declares solemnly, “Everybody got to die.”

“You know what the best kick of all is?” another asks. “It’s when you put a gun on grownups and watch them go all to pieces and blubber right before your eyes. That’s the best.”

Algren loved music nearly as much as he loved literature, and I sometimes think of his work in musical terms. To my eye and ear, his best books—Never Come Morning, The Neon Wilderness, The Man with the Golden Arm, Chicago: City on the Make, and Nonconformity, are all blues—but A Walk on the Wild Side is punk. The first are all ruminations on the human condition, rhythmic, meditative works that can speak volumes with their absences and elisions, and impart messages so subtly they linger in the mind and change lives. The second, like the best punk albums, is of its moment—a report on injustices and slights, angry art with a message. To my mind, both forms have their place. Both should inform our culture. Both may well be masterpieces, though of a different sort. But one looks inward, tries to reckon with the quality of the human soul, and the other looks outward, announces our collective failings, passes judgment, and demands retribution—and as a reader and a listener, I privilege the former over the latter.