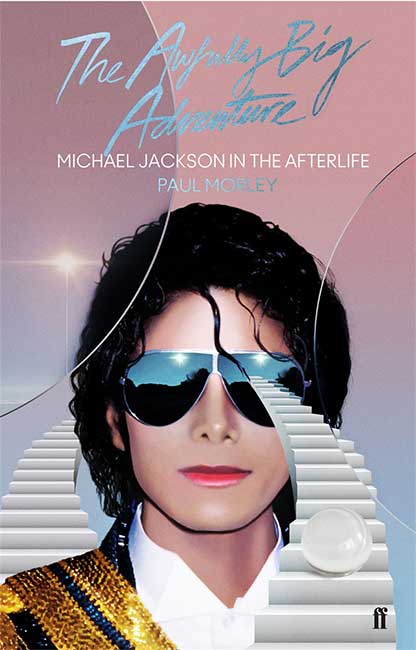

The Awfully Big Adventure: Michael Jackson in the Afterlife, Paul Morley (202pp, £10, Faber)

Like most of Paul Morley’s books, this isn’t really about it’s supposed subject matter. It’s as much about the author as Michael Jackson, as much about society, music and fame, is basically ‘the continuing adventures of Paul Morley’s brain’. With one proviso: this is a ‘new and expanded’ version of an essay that first appeared in the second edition of Loops, a short-lived serious music magazine Faber produced.

The failure of Loops, which Morley refers to in his ‘Awfully Modest Introduction’ (it isn’t) perhaps gives us an indication of why this book feels like Morley treading water. Back in the day of course, Morley was one of the people who overturned and revolutionised music criticism, bringing deconstruction and cultural theory into the music weeklies and beyond as post-punk and other new music swept aside the complacency and expectations of the 1970s. Morley was slightly different from other writers, however, as he liked pop as well as experimental music; he thought anybody taking music seriously would take all music seriously. And he put this theory to the test: starting ZTT with Trevor Horn and launching both Frankie Goes to Hollywood and Propaganda into the world, and contributing to The Art of Noise collective. He’d also pop up, as he still does, on radio and television arts programmes, offering cultural commentary and critique.

Loops was launched to counter both the nostalgia of the rock monthlies with their endless re-runs of the rock canon, and the disposable remnants of the weekly or monthly pop press (in 2010 still in its death throes before everything went online). The first issue seemed like a breath of fresh air: an A4 magazine with a spine and a wide-ranging mix of serious writing on serious musicians, but issue 2 was a step too far. It seemed that most of the issue was Morley’s essay on Jackson, and the rest was just too offbeat. I mean, Serge Gainsbourg, Napalm Death, Prince and the Cramps? Come on… Anyway, Loops issue 3 never happened, and the two issues got filed away on my shelves.

One of the misunderstandings I think, is how little the likes of Michael Jackson impinge on the listening habits of many music fans. Of course I know who he is, but talking about Jackson with some students yesterday – they remain huge fans, but that only means they have five or six mp3 songs on their phones – I was saying how I’d only engaged with Jackson twice in my life, apart from fleeting tracks on the radio or gig PAs. First was when I shared a house in Coventry for a year and Steve had Off the Wall on heavy rotation; second was when I was at university and several friends waited up to see the ‘Thriller’ video played for the first time, just after midnight on the day of release. Oh, and I think I cheered Jarvis Cocker on as he waggled his arse in front of Jackson being crucified (or whatever it was) to save the world at some big event. So maybe three times.

And of course, it’s either very fortuitous or very unfortunate that this book’s publication, carefully planned to coincide with ‘the tenth anniversary of the singer’s death’, is in the shops hot on the heels of a new documentary showing overwhelming evidence that Jackson was a child abuser and drug addict. My students don’t care, and neither it seems do many fans – Jackson’s albums are selling like hotcakes again – but I wouldn’t touch them with a bargepole. Besides, it’s not my kind of thing.

But we can’t blame Morley for any of this. What, however, is this book doing in 2019? It’s looking backwards at how we, as part of society, might take some blame for inflicting fame on a young singer, for allowing alleged parental abuse to happen, for allowing the music industry and the fashion industry to sweep Jackson up into wealth, confusion, mental instability and drug addiction, institutional and self-inflicted racism. And questioning the idea that a middle-aged rock star should be indulged with the offering-up of sacrificial young friends by their parents for sexual and emotional abuse as well as financial indulgence.

Once Morley’s self-analysing and somewhat explanatory introduction ends on page 30, the book becomes a series of numbered sections, 1-38. Some are single paragraphs, others are essays in themselves; three are google lists of the ‘Michael Jackson is…’ variety, which feel like a rehearsal for Morley’s more recent book on Bowie. However elucidating, informative and entertaining parts of this book are, I can’t escape the fact that I am simply not interested in the singer that this project is hung on. The critiques of fans, record companies, courts, families and the media are top-notch Morley, but I can’t help but get the feeling – and this is supported by Morley’s introduction – that he thinks he ought to be writing about this international pop star who (at the time) had recently died.

However hard Morley tries to bring his enormous intelligence, wit and sparkle to the subject matter, he’s not that involved. The close of the book seems to support this:

Michael Jackson had entered, through the darkness of some messy, miserable final moments, a different life, one that seemed instantly to hint at making sense of his role in our lives, of his tenacious, reverberating position in our imagination.

He had, after all, found his way home. A haunted house. He shut the door. He turned out the lights. His eyes adjusted to the dark. He thought of nothing and no one. His brain stopped burning. The bass started grooving. he was in control. He didn’t move a muscle.

I looked at him for a while and then I left him where he was.

This book is the document of Morley looking for a while, then moving on. It feels tentative and distant, almost totally disengaged from its subject. Whereas Morley was clearly a Bowie fan and The Age of Bowie reflected that, just as Joy Division and The North also showed the author’s deep engagement with his subjects, there’s something cold and removed about this book. The Awfully Big Adventure feels like an autopsy report rather than a celebration or response. Morley seems as confused here as I am after re-reading it.

© Rupert Loydell 2019