Concerning the films of Luis Bunuel one critic noted a key feature of the director’s later work – or, rather, the social climate of the time as depicted therein – a society that appears ‘thoroughly pleased with itself’ and capable of the ‘firmest suppression’ of any indications of trouble. Crucially, our critic also said, ‘This is a world beyond satire, and the old disruptions of Surrealism are not going to make any mark on it, because ordinary life, in this place, is already as arbitrary and erratic as anything a Surrealist could dream up.’ Are there fundamental problems with Surrealism?

Taking into account Sartre’s critique of a ‘curious enterprise of achieving nothingness through an excess of being’ one might also add that there are significant issues with political idealism, infantile regression, anti-consumerism, post-colonialism, religious primitivism and The Turn To The East which might define Surrealism as a precursor of the regressive Left. Although it should be noted that, for the Surrealists, freedom of expression was far more important than any political dogma which is why an attempted rapprochement with the Communist Party eventually fizzled out – for, as Andre Breton himself said in 1935: ‘propagandistic poetry’ amounts to a denial of ‘the historical conditions of poetry itself’.

From our present vantage point we should be able to formulate a ‘post-surreal’ or neo-Surreal perspective, countering, or, neutralizing such vexatious, problematic questions.

The idea of a ‘typical post-Surrealist viewpoint’ is mentioned by Lucy R Lippard in her discussion of the art of Valerio Adami, a body of work, focused on the principle of metamorphosis, but which also draws on the media-sphere, especially advertising. To quote the artist himself: advertising is ‘a language that assails you wherever you go’. He said his aim was to realise a condition where ‘time and space spread out into a new psychic action’.

A new psychic action?

Perhaps there is also a variation of materialism which, for the sake of convenience, we might call Subtopian Materialism, a self-consciously decadent form of Pop originating circa 1955 in the ‘edgelands’ and ‘cultural desert’ of London’s urban fringe.

Subtopian Materialism includes Tabloid Impressionism, a trash-aesthetic tactic, a type of post-surreal Urban Alchemy. The principle of Objective Chance applied to the mass media, particularly in its most disreputable aspects where the Spirit of Seriousness is much diminished, or with luck, completely absent: downmarket advertising, the tabloid press, junk mail, celebrity culture and tacky TV, lo-fi mass production movies, burlesque performance and so on and so forth. Also, a slangy literary style: a form of verbal slumming or nostalgie de la boue often incorporating the disregarded poetry of obscure jargon, argot, lurid journalese found phrases, wacky neologisms and, in a more contemporary mode, Cyber-Junk (1).

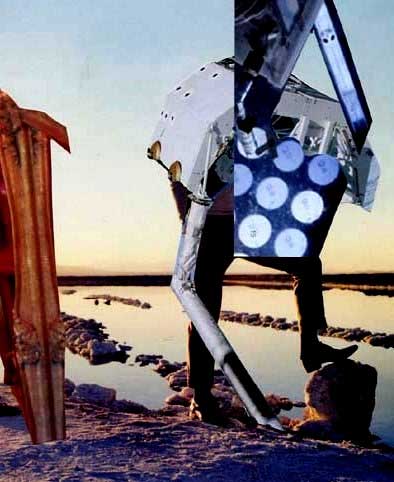

Subtopianism finds inspiration in boring streets and brutalist architecture; incongruous electricity substations, deserted allotments, sewage works, seedy flea-pit cinemas, golf courses. in the accidental poetry of rusting wire fences, ‘admass’ (mass consumerism) and all forms of popular entertainment from Cinerama to Teaserama, and inevitably the indeterminate, sub-surreal no-place of featureless suburbia – the commuter belt, an ‘edgeland ‘ locale, a netherworld or interfacial interzone where ‘nothing really happens’.

Mid-fifties Subtopian life was dominated by ‘the balance of terror’, by flying saucers and the fear of radiation but found Sunday lunchtime solace in Family Favourites requests (Tin Pan Alley, Broadway, skiffle, cha-cha-cha, the mambo craze, Shirley ‘the Zither Girl’ Abicair), horror films, Jet Set glamour, and exciting, new gadgets – like the Xerox Copyflo and the Polaroid Instant Camera. For exoticism, fashion, scandal and thrills, Subtopians looked to the Blond Bombshells, to the Sweater Girls (bless ‘em!) and divas such as Diana Dors, Julie London, Gina Lollobrigida and Jayne Mansfield; to Nabokov’s Lolita or to TV starlet Sabrina. Yet, to a critical observer like Ian Nairn, Subtopia was merely an anonymous liminal zone or tract of anomic space – a product of bad urban planning lacking in distinctive character or ‘spirit of place’ – an interstitial ‘middle state neither town nor country’. In hindsight it seems that ‘Subtopia’ (‘inferior place’) was an incitement for the imagination; although it might also have been that its bizarre strangeness was not a subjective projection but a discovery – the edgeland of Subtopia was bizarre in itself, the locus of a new quasi-surreal psychic action.

- Cyber-Junk (or Cyber-trash). Subtopian Materialism meets kitsch and creepy B-Movie Sci-Fi in cyberspace littered with cosmic debris. Well, sort of.

Bibliography

Breton, Andre, Manifestos of Surrealism, University Of Michigan, 2007

Lippard, Lucy R, Pop Art, Thames & Hudson, 2001

Nairn, Ian, Outrage. On The Disfigurement of Town and Countryside, Architectural Review Special, 1955

Sartre, Jean-Paul, Modern Times: Selected Non Fiction 1938-1973, Penguin, 2000

Wood, Michael, Belle de Jour, BFI, 2005

A C Evans