DADA, POP ART AND NORMALITY MALFUNCTION

The cultural landscape is like a labyrinth, or ‘The Garden of Forking Paths’ described in a short story by Borges. At every twist and turn there is a bifurcation, every tendency or movement of distinct character has its antecedents and precursors, its splinter groups and secessionists, its side effects and unforeseen consequences. Just occasionally it is possible to unmask the normative injunctions of repression embodied in the reactionary dogma of autonomous, transcendental values, that ‘spirit of seriousness’ (l’esprit de serieux) identified by Jean-Paul Sartre as the antithesis of freedom.

The End of the Victorian Dream

With their fascination of urban life, show business and modern communications it is quite possible to identify Aubrey Beardsley and other late Victorian Decadents as precursors of Pop Art. Similarly Arthur Rimbaud, in the ‘Alchimie du Verbe’ section of Une Saison en Enfer recalled how he found the celebrated names of painting and modern poetry ‘laughable’. He preferred ‘stupid paintings’ or stage sets, ‘popular engravings’, old operas and ‘ridiculous refrains’, not to mention erotic books with bad spelling. Rimbaud has cult status in US Pop Culture thanks to celebrity endorsements from Jim Morrison and Patti Smith.

There is an anarchic tendency in Modernism that subverts ‘high art’ and ‘serious’ elevated Arnoldian, Victorian notions of culture as ‘sweetness and light’, questioning ontological and epistemological certainties.. This anarchic tendency can be amplified by the incorporation of external or ‘exotic’ influences that contradict existing, traditional and academic representational conventions offend middle-class Puritanism or derail the validity of utopian ‘revolutionary’ alternatives.

For example, an important feature of Beardsley’s graphic work was the incorporation of Japanese design elements. The discovery of Japanese art, especially woodblock prints, by many Western artists was a prime factor in the establishment of a more ‘modern’ look to pictorial imagery. The austerity and simplicity of ‘traditional’ Japanese style pushed artists into a new approach, freeing them from nineteenth century academic conventions. For Beardsley, as explained by Linda Zatlin, the influence of Moronubu and Hokusai provided an escape route from both Classicism and Romantic Medievalism, allowing Aestheticism to challenge Victorian clutter and the domination of Ruskinian realism.

Beardsley’s described his new style as an art of ‘fantastic impressions, treated in the finest possible outline with patches of Black Blot.’ In his illustrations for Salome (1894), the exploitation of Japanese style, incorporating calligraphy and other unexpected approaches to format (the use of borders, fine line and general pictorial composition) created an overwhelmingly novel effect, a ‘perversion of the Victorian ideal’ (Zatlin). By these means Beardsley became a pioneer of Art Nouveau and changed the look of Western visual design forever. These elements of style, the ‘fantastic impressions’, the austere linearity, the problematic moral content, the non-Western influence were all ahead of their time, intimations of shifting cultural trends, a new twist to the idea of The Modern. Fantasy, claimed G S Kirk, ‘expresses itself in a strange dislocation of familiar and naturalistic connections and associations.’

The Anti-Hero of Anti-Art

In The Cubist Painters (1913) Apollinaire asserted that a new kind of art was capable of producing works of power not seen before, even fulfilling a new social function. To reinforce this idea he used the image of Bleriot’s aeroplane ‘carried in procession through the streets’ just as, in times gone by, a painting by Cimabue was ‘once paraded in public procession’. This was the conclusion of a short discussion on the work of Marcel Duchamp (1887-1968), described as an artist ‘liberated from aesthetic preoccupations’.

Commentators like Jacques Barzun saw ‘Abolitionism’ as part of a reaction to the Second World War, but, in fact, an anarchic, ‘near-nihilist’, anti-art tendency was gaining ground much earlier – perhaps the Richard Mutt Case of 1917 signalled another watershed in the relentless dissolution of the old order. One must certainly note the historical significance of the moment when Marcel Duchamp decided to abandon painting in favour of the Readymade. One must note also that Richard Mutt’s ‘Fountain’ still attracts enormous interest at Tate Modern and, as Patricia Roseberry observes, ‘anticipated by many decades the sort of art which receives general attention and provokes discussion’.

Clearly, Duchamp – whose iconoclastic spirit presided over many aspects of the post-war Neo-Dada scene, from Fluxus to Nouveau Realisme, from Kinetic Art and Op, to Conceptual Art – was the prime instigator of anti-art – he was, one might say, the anti-hero of anti-art.

By 1912 he had rejected the direction of the avant-garde Cubists which he found far too narrow, or to use his terminology, too ‘retinal’. Duchamp realised that the self-reflexive materiality of abstract painting would, sooner or later, lead to dead end; a view that had already been articulated by the Vorticist, Wyndham Lewis.

One of Duchamp’s responses to this situation was the innovation of the Readymade.

The Readymade, a precursor of Conceptualism, exemplifies two facets of estrangement: displacement and transgression. It was a mass-produced artefact chosen by the artist on the basis of neutrality. All of these objects, including, among others, the Bicycle Wheel (1913), the Bottle Dryer (1914), the Snow Shovel (‘In Advance of a Broken Arm’, 1915), Comb (1916), and the Urinal (‘Fountain’ signed ‘R. Mutt’, 1917) represented a radical shift away from the tenets of orthodox aesthetics. These anonymous objects, displaced from their utilitarian contexts, actualised on the physical plane a disconcerting element of Modernity – an element eventually identified as ‘surrealist’.

Partaking of black humour, they also displayed an affinity with the displaced objects that featured in works of the Scuola Metafisica, paintings such as ‘The Evil Genius of a King’ (1915), ‘The Enigma of Fate’ (1914) and ‘The Disquieting Muses’ (1925) by Giorgio de Chirico, master of post-Classical alienation. This proto-surreal, disquieting element can be traced back to the art of previous phases, for example the ‘weird’ Classicism of Piranesi and Fuseli, or David’s ‘super-cool’, unfinished ‘Portrait of Madame Recamier’ (1800), all the more effective for its unfinished state.

A transgression of normal expectations, displaced objects occupying physical space in the ‘real’ world, outside the picture frame, Readymades represented a ‘radical’ aesthetic violation soon to become the basis of Dada.

Like Duchamp, Dada (established in 1916 at the Cabaret Voltaire, Zurich) dissociated itself from both the ‘official’ avant-garde and from the overarching moral (religious) narrative of social respectability and bourgeois complacency, a narrative of pernicious complacency seen as a cause of the First World War. In a diary entry dated June 16, 1916, Hugo Ball, the Magic Bishop, referred to the Dada enterprise in terms of theatrical entertainment: ‘the ideals and culture of art as a program for a variety show’. Performances at the cabaret involved Bruitist Music, Simultaneous Poetry and Cubist Dancing. Huelsenbck said ‘the liberating deed plays a most important role in the history of the time.’

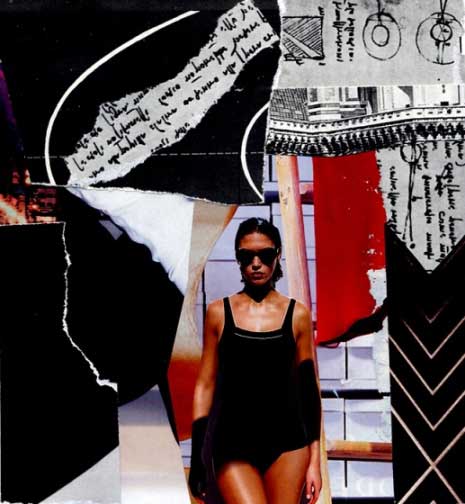

Dada publications were produced in a suitably ‘radical’ manner that still seems fresh today, incorporating extreme typography, startling photographs, montage, collage, overprinting, disrupted reading order and a close intermixing of word and text just like a Web Page. This explicit rejection of the official avant-garde by Dada, and later by the Surrealists, can be seen, in hindsight, as an early stage of a ‘Post-Modernist’ sensibility. For the Dadaists and their allies, like Duchamp and Picabia, conventional or established Modernism was closely allied to, if not identical with, a failed, once revolutionary ‘avant-garde’. But this was now a pseudo-radical avant-garde because it had become ‘official’. It was internationally accepted by the cultural elite and consequently assimilated into the global art market system.

This official avant-garde could no longer drive change – change required total demolition – Dada was the first stage of the Post-Vanguard era, the precursor to various aspects of Post-Modernism because it had moved beyond the prevailing normative definition of Modernity. As a phenomenon Dada was a ‘normality malfunction’, it was a breakdown of accepted standards, it was a violation of the prevailing order: it was the cultural equivalent of a ‘wardrobe malfunction’ or defaut de fonctionnement de garde-robe. Dada and Surrealism were ‘Post-Modern’, because they superseded Modernism as a radical movement and prefigured subsequent developments such as Pop. It was a continuation of Duchamp’s rejection of Cubism, confirming the idea of an alternative, divergent lineage distinct from Late Modernism. Tristan Tzara went further and claimed that Dada had nothing at all to do with Modernism.

Mass Production and the Final Fade Out

It was the Neo-Dada Pop Artists who became the post-war advocates and heralds of this new era, this emergent meta-culture. For example, far from seeing the consumer society as a nightmare of cultural degeneracy, the London Independent Group (IG) formed in 1952, set out to ‘plunder the popular arts’ with, according to Richard Hamilton, the strangely archaic objective, of recovering ‘imagery which is a ‘rightful inheritance’. Curiously this was seen as a way of protecting the ‘ancient purpose’ or Primitive role of the artist. On the other hand, for Edward Lucie-Smith, Pop was about ‘the tone and urgency of the modern megalopolis’ an attempt to forge an art of ‘majority living’ for ‘men penned in cities and cut off from nature.’ By coincidence it was also in 1952 that researchers ‘re-discovered’ the earliest known heliographic image, Niepce’s ‘View from the Window at Le Gras’, hidden in a family attic.

For the guru of British Pop, Lawrence Alloway (1926-1990), Greenberg’s type of cultural politics was redundant and ‘fatally prejudiced’. Alloway revelled in the anti-academic style and iconography of the ‘mass arts’, seeing the pejorative use of a term like kitsch symptomatic of an outmoded view. He looked at the art world and saw the collapse of an intellectual elite fixated on upper class ideas and ‘pastoral’ representational conventions; an elite who could no longer set aesthetic standards or ‘dominate all aspects of art’, as had been the case in the past. Furthermore it was an elite that had assimilated for its own purposes the traditional agenda of the avant-garde, which was now a diluted and spent force, a ubiquitous, corporate International Style. There were anodyne abstract paintings in every boardroom and office lobby. The grand narrative of stylistic internationalism had become dissociated from the popular base, a phenomenon apparent in all spheres and not just architecture and avant-garde art. In music for example, Schoenberg’s ambition that composers of all nationalities would move towards the dodecaphonic method proved hollow. In terms of general cultural significance Derek Scott is surely correct when he observes that ‘the 12 bar blues may be said to have greater cultural importance than the 12-note row’.

Mass produced ‘urban culture’ was to provide the raw material for different type of art. Fascinated by a world of movies, television, production lines, advertisements, fashion, pop music and science fiction, the IG simply accepted all this as ‘fact’ – as a tissue of signs, or as a form of information exchange. In popular art, asserted Alloway, there is a ‘continuum from data to fantasy’ and Pop artists were engaged in a kind of anthropology of the meta-culture. The notion of an autonomous, disinterested ‘fine art’ was completely rejected in favour of a Space Age populism, seeming, in hindsight, to synchronise with official doctrines of nuclear optimism like ‘Atoms for Peace’ (1953).

By 1959 kinetic artist Jean Tinguely (1925-1991) had developed his metamecanique Meta-matic machines for ‘do-it-yourself abstract painting’. Meta-matics were portable, tripod or wheeled devices with co-ordinated drawing arms. ‘Meta-matic No 14’ was a hand-held drawing machine shown at the Art, Machine and Motion event (a typical Neo-Dada provocation) staged at the ICA in London. Operated by a girl in fishnets dressed as an usherette, the device produced numerous Abstract Expressionist works for distribution amongst the audience.

Tinguely also developed the ‘Cyclomatic’ a pedal-powered version of the device constructed from welded scrap metal and bicycle wheels. At the ICA event cyclists mounted the machine in turns competing to see who could produce a mile long abstract painting in the fastest time. Closely related to the ‘Cyclomatic’ was the ‘Cyclograveur’, a static pedal-powered device capable of drawing on a blackboard.

Earlier in the same year Tinguely had shown his Meta-matics at the Iris Clert Gallery in Paris at an event attended by Marcel Duchamp. This was the final fade-out of the revolutionary avant-garde, the negation of the art object in favour of informational media and delirious Cold War Space Race techno-fashion. Catsuits, PVC boots and body armour – these were the new objects of desire. This was the beginning of a new age of normality breakdown – it was the end, of an era; it was the beginning of a designer Space Race.

AC Evans