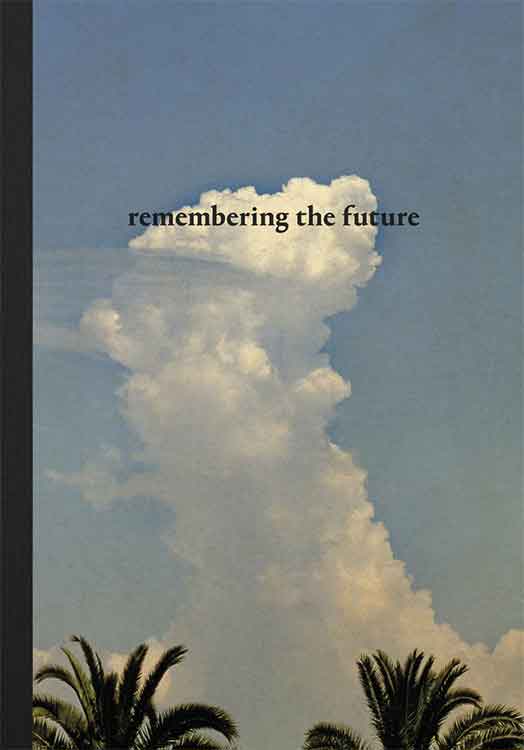

remembering the future, albarrán cabrera (RM Verlag)

albarrán cabrera is actually a duo of photographers working together under one name, with a particular interest in frozen moments and the possibility of memory and future possibilities, and a diverse and original use of photographic processes. Their regard for and interest in Japan (viewed from Spain) and unusual and combined printing techniques, including the use of gold leaf, is foregrounded in this book: these are contemplative moments caught on camera, strangely removed from any narratives or sense of ongoing events.

This is slightly at odds with the photographers’ foreword and Amanda Renshaw’s ‘short text’ which both precede the images in this book:

We are our memories. They define what we are and help us to understand our reality.

[…]

Thinking about the past and future can seem different activities, but when we think about the future, we do the same mental work as when we remember. We just remember a future that hasn’t happened yet.

Apart from the fairly simple idea of the light changing, or fishes continuing to swim, I don’t read these beautiful photographs in this way. They are very still, calm images; static with a focus on texture and detail, and a strong design sense; they are almost timeless. Many are of distant landscapes or cloud formations, subtly printed in blues and golds and greys; in one a terrapin or turtle rises to the surface of a pond; in another an orange and green tree is silhouetted against a golden moon. Elsewhere, rocks, light and reflections are abstracted; sometimes layers of the image are blurred and hardly present. (Amanda Renshaw suggests they are ‘misty as if faded with time’.)

These are exquisite images, perhaps most akin to traditional Japanese haiku (not the bastardised English syllabic version) where the seasons feature, as well imagistic pictograms. Here (Renshaw again) ‘[a]ll these visions become interwoven tales of presence, absence, fragility and permanence’, details of the world we might otherwise never see or engage with. Even when an occasional human presence is visible – the raked stones of a zen garden, a wall behind a tree or water pouring through a concrete channel – it is the natural world we focus on here. If one or two of these images feel almost too rich and beautiful, in the main they are subtle and unusual takes on the world around us.

If I can’t agree to the idea of ‘remembering the future’, I am happy to accept that these photos ‘portray fragile, intangible and fleeting moments of impermanence, warmth, shadow, water and light’ and that the photographers ‘seek to inspire our imagination and conjure up distant emotions or echoes of our own past experiences.’ (Renshaw) Echoes and traces of the past seems an appropriate summary and enough of a motive, and this book is a wonderfully produced artefact to contain and present such ideas.

Rupert Loydell