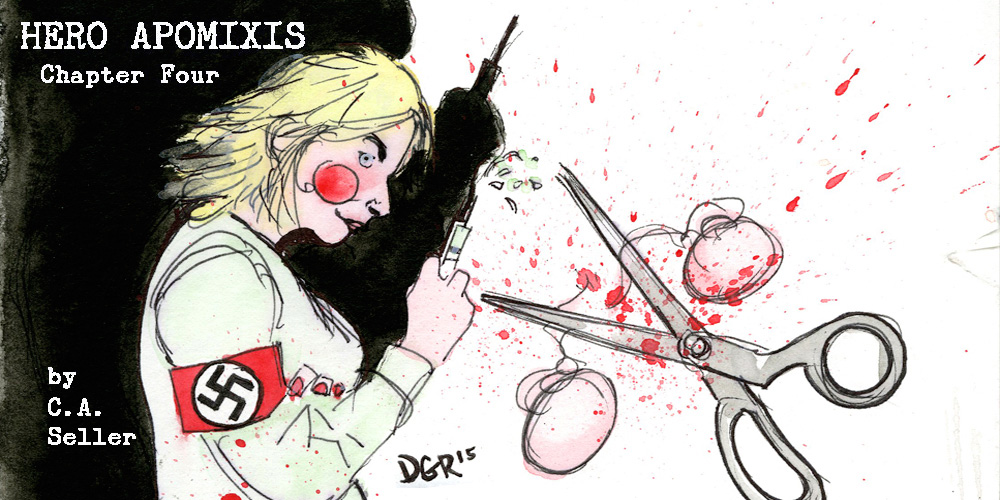

Synopsis of Hero Apomixis by C.A. Seller

Hero Apomixis is a work of stream of consciousness written over 22 months while the author was incarcerated in Attica Correctional Facility in 2000/01. A story of tortuous experience at the hands of a broken social services system, bad parenting, and the Prison Industrial Complex, Hero begins to lose his mind as evidenced by fantacide and dreamories only interrupted by prison feedings. Hero is either a victim or a sociopath. The book challenges us to ask, “What would you do?”

“If you like Dante, if you like Bosch, if you like Burroughs, you’ll dig the brutally dark brilliance of C.A. Seller’s HERO APOMIXIS. A rare stroke of ever darkening courage. Welcome to hell.” Ron Whitehead

https://www.amazon.com/Hero-Apomixis-mr-chares-seller/dp/1517359465?ie=UTF8&*Version*=1&*entries*=0

CHAPTER 4

Hero had been released from prison three times in the

preceding fifteen years plus one time from Rikers Island

after a six month city bid for a sum total of seven years

inside – so far. He dreamt about jail. He’d been arrested

over twenty times but didn’t think that he was terribly

bad compared to any of the cons around him – just not too

swift when it came to exercising a little better judgment

sometimes. He always remembered feeling alone, and scared,

and then making a dumb mistake. Still, Hero had gotten away

with all sorts of shit and had been locked-up for all sorts

of shit (some of which he hadn’t even done). From turn style

jumping to armed robbery – no sex crimes or hitting women –

unless they hit him first – and even then. All this in and

out taught him by year five that if they took him off the

street because he wasn’t taking responsibility for himself,

getting into trouble and so on, and then they stuck him

in prison where he had virtually no responsibilities, then

they really couldn’t expect too much from him now could

they? And that went for almost 95% of the criminals in the

system. Plenty of dudes were Big Willy’s in the joint where

everyone knew them, respected them, and feared them. They’d

made their little moves on the inside slinging drugs, extortion, gambling and what have you and they were somebody.

Once they were out and got off that bus that had taken

them from the jail to the Port Authority on Eighth Avenue

and 42nd Street, they were nobody. NO-BAH-DEE, baby.

“You’s a motherfuckin’ NOBODY, Jack. You nobody goin’

nowhere fast and yo’ ego is layin ‘ over there under that

payphone next to dat derelic’ pukin ‘ up. You better hurry,

boy, if you wanna keep it clean, go on now,” the voice in

their heads whispered. And if they were lucky enough to

have been listening – then they had a choice, maybe.

Hero had heard stories, mostly second and third hand,

about some dude who’d got off that freedom ride and stood

there on Eighth Avenue looking just like a lost kitten until

he’d made up his mind and hooked off on the first police

he saw so they’d send him back up north where everything

was familiar and there weren’t any bills to pay; where everyone

knew who he was.

Hero couldn’t understand why the cops hated them all so

much, especially in the joint, in the street, in general.

Hadn’t anyone ever had the presence of mind to change the

system and risk looking “soft on crime?!” Oh, yeah, he’d

almost forgot – they said it was working. Well, that depended

on what your definitions of “it” and “working” were. America

had a lot of people in jail, way over a million, Hero’d

read somewhere, maybe even two million. California alone

had 165,000 incarcerated men and women. New York held 97,000 and the state would build more prisons before they’d ever

build more schools: “Just as well! Most felons never finished

high school anyway!” barked the cozy logic of the right.

And, if they could, Hero knew that “they would spank each

and everyone of us with a bullet in the back of the fuckin’ head.”

Whenever he looked around, he saw a lot of not so undercover

Nazi’s with badges: the cops; the prisoners: black ones,

white ones, Spanish ones; plenty of Nazi’s. There was no

shortage of Fascists. What appeared so simple to Hero, was

impossible for all of the ignorance. “Applied Ignorance.”

What would he do if he could do almost anything he wanted

with all these people that constituted the bulk of a very

painful societal thorn?

“Did I say ‘thorn?’ Sorry, I meant ‘prick.’

Wipe out an entire generation or two (or three) like they’d

done in Cambodia? No, that hadn’t worked too well when they’d tried it. Send everyone out for re-education, sensitivity

training, encounter groups and free tofu pizza?

“Applied Ignorance,” Hero heard someone whisper softly

in his left ear again.

“Rules of The Revolution, Rule #13: People

secretly desire that they be told what to

do and actually detest choices.”

“Rule #14: People hate change and fear the future

for those very reasons (see rule #13).”

Hero was too smart for his own good. He’d been hearing

that admonition of his behavior for so long that it was

like his motto now – his own personal Catch-22. Sitting

on the edge of his bed with his head in his hands, chin

on upturned palms, fingers splayed over closed eyelids;

on his right Hero saw the poorly formed white outline of

a man being shot with a big white bullet that came from

the left and took the man’s outline away, folding it in

on itself as it traveled farther to the right and then disappeared

altogether. The source of the bullet wasn’t clear;

from a gun that didn’t make any noise. The whole thing looked

very scratchy, like an old film.

Hero ate two packets of sugar to see if that would stop

the feeling he was having of riding in an old elevator as

it comes to a stop, bouncing a little on huge worn-out springs.

He thought that whatever it was it had gotten worse in

minute increments. He dreaded going to sick call. There

was only one nurse in Attica who’d ever helped him; the

rest were nasty, short tempered, mealy mouthed, and – quite

simply – just bad nurses. One of them had told Hero he didn’t

have Hep C when he knew that it was all over his records because he had his own set of copies! (She’d told him that he was

wrong – not reading the records correctly.)

The bad nurses were always hostile, suspicious and accusatory.

As far as they were concerned no inmate told

the truth, they were all incorrigible liars and always lied.

Always. They always lied. All of them, liars. Liars, liars,

liars, every last one of them.

Sick call was where Hero had first heard one of them say

“Welcome to Attica” in a tone so sarcastic that he’d had

trouble believing it had come out of the nurse’s mouth.

He’d had very bad hay fever and went to get some allergy

pills and a few small foil packets of bacitracin ointment

for sores that had developed inside his nose. Hero’s medical

records showed that this was a recurring problem that had

always been treated this way.

“You don’t want to use bacitracin,” a nurse that resembled

an old molting owl screeched at him, “you wanna’ let’em dry up,” and then she looked Hero dead in the eye and said,

“Welcome to Attica.”

It was like blaming the jail for the sour excuse that she’d invented. Half-drunk, in the bar across the street from the prison,

she would carry on about how easy the inmates had it; justification for her vile treatment of them no doubt. An admittedly illegal form of punishment that she had made it her

personal responsibility to mete out. The C.O.s at the bar

loved her when she got like that.

She’d never even looked in Hero’s nose, or his file, when

he’d mentioned that they always gave him bacitracin. He

reflected on how this nurse who, on second thought looked

a lot more like The Wicked Witch of The West, frustrated

the health of prisoners’ costing the state more money to

steadily accomplish less.

Hero got some bacitracin from the good nurse the following

week when he was allowed to go to sick call again.

“Once a week,” the bad nurse had told him, “Welcome to

Attica.”

It was a scary crap shoot, you never knew who might be

working.

The good nurse was an attractive German woman in her forties

who had, what Hero imagined, were some very pretty tits.

She was a very nice lady and gave him everything he’d asked

her for. He said she was most kind to him and he was extra

polite and very grateful to her. He dreaded going to see

one of the bad nurses for anything, never mind with something really serious.

The NYSDOCS policy towards major illness was very much

like that of General Motors. Not their employee health plan,

oh no. It was how a $2.40 part the company could’ve installed

to keep the car from blowing up – wasn’t – because

they’d run a “cost benefit analysis” that showed them it

would be cheaper to leave the part off and just field any

lawsuits that came about as a result instead. Lawyers for

husband before the accident proved beyond a shadow of a

doubt that the part would have saved his life; how GM had known and ignored one of their own engineer’s recommendations so that in the long run they were ordered to pay the sad woman $50 million.

NYSDOCS theory in practice was identical to GM’s in that

regardless of the number of inmates with say, Hep-C for

instance – only a handful would try to keep up with their

care and ask the doctor questions; research their illness;

filing grievances and lawsuits while NYSDOCS dragged their

leaden feet betting that these troublesome inmates would

either die – give up – or be released – in that preferred order.

A lot of cons believed whatever NYSDOCS told them or

didn’t believe anything NYSDOCS told them without more

than what was really only bad triage many just got sicker

and some died. A small percentage sued and, if they won,

it was still much cheaper by far than treating every prisoner.

Put all together Hero believed that if they could, the

majority of NYSDOCS employees would have gassed the inmates just as soon as look at them. In the bigger picture The Big Lie explained – upon even the least cursory of examinations – the relationship between people as consumers

and information about any large numbers of “other” people

unrelated to them in any way. He saw it in news reports:

estimates of tens of thousands and hundreds of thousands

of people murdered by bad people in distant parts of the

globe. Surely, how effected was he or anyone else? As a

consumer it was nothing but another sound bite consistent

with millions of other sound bites that were repeated

in content and delivery over and over and over again until

Hero thought that if he could run a large enough quantity

of them together – back to back – that an accelerated narcotic

effect could be produced. A trance of indifference would

come over the viewer as the same emotional receptors were

fired into again and again, dulling the response so that

the deaths of 100,000 East Timorese would be received no

Jews. A rise in the local sales tax meant more. He’d just

move on to the next show, the next TV listing or what

video to rent, what to have for dinner that evening and,

say, did you catch the Giants Monday night? Hero saw the

correlation in the media (and subsequently the politician’s

view of criminals) as one pushed the other and they both

pushed the consumers to fear, familiarize, and spend, spend,

spend. What they saw is not what they got and knowing that

didn’t disturb them as much as he thought it should have.

Individually, most human beings could comprehend another

single or small number of other human beings without forgetting

who they were, what they were, that they were primarily

individuals like they themselves. Larger groups had

no face and were easier to ignore or simply reject as a

whole, right or wrong, they were – after all – the problem,

weren’t they? Who would ever admit that such a hidden philosophy of perverted values existed?

The Big Lie was always unassailable in that its images

would not be held accountable. It didn’t have to refuse,

it simply exercised applied ignorance. From clean shiny

top to dirty wet bottom we were all perpetuating The Big Lie.

Hero knew that even if he proved it with physical evidence,

the consumer would just shake his head and tell him he was

crazy. And the evidence was everywhere, the true battle

laid within the consumer’s perception. Why? Because, he

believed The Big Lie. And if everything looked and smelled

exactly like shit sometimes, that was because it usually

was. This was no longer about escape – this was rapidly

becoming a question of perversion and perspective.

Hero wished he’d been born in Canada, they all had health

cards the government gave them for free, the whole fucking

country went to the doctor for free.

“A healthy nation – what a concept,” he said to the wall.

He’d heard it was the same thing in Europe, too. Only the

largest industrialized nation in the world had citizens

with cancer who made too much money to be eligible for government assistance, but too little to afford private health

insurance – so that many of them languished in pain and

misery without treatment instead waiting until they became

so sick that they had to be hospitalized – which some of

them still tried to avoid so that they wouldn’t burden their

families with the debt. Death Of A Salesman. Willy, what

was his name? It was all he could think of at that moment.

Hero “felt” the floor move. It reminded him of being in

an old building downtown whenever the bus went by you would

feel it through the floor and then, after about half-a-minute,

you would hear it as it passed around to the side of the

apartment to rattle the windows.

When he was a young boy spending summers in Connecticut,

he used to stand on the floating wooden dock anchored off

the beach in the lake where he’d learned to swim. It would

bob up and down and left and right so very softly with the

easy waves. The water ebbed that way during

bittersweet summers when he’d learned how to swim – but

not how to fight. When he’d learned all about anti-semites

up close after being asked to wait outside while all the

other children went into TT Volpe’s house and came back

out with big cookies. TT was uncomfortable, they couldn’t

have been much older than nine or ten, when he told Hero

that his mother didn’t want any Jews in the house. That

was the first time. He’d discovered there would be more.

Even people he thought were his friends would do it, it

was incredible. There was the question of, “Why?”

“Because they’re sons-of-bitches, that’s why! ”

“My father was a fool,” Hero said for what had to easily

have been the 923,465th time.

It was as if he’d been marked from the earliest, maybe six

or seven years old, to be tortured by bullies his entire

life and that had helped him to develop a voluminous capacity

for horrific and physically damaging violence. Hero’s mother

and father had bullied him; his sister – that fucking witch-

10 years his senior no less; his teachers – who grew impatient

with his involuntary, spaced-out mental stasis; acquaintances,

friends, bosses, his own stupidity, all the lawyers, cops,

judges, and psychiatrists and on and on it went. They were

all like dogs who, after smelling Hero’s nervous fear,

would bark and bite with ferocious confidence. He was

too tired to worry about all of them or even mean nasty

nurses who weren’t qualified to treat a hangnail.

“Fuckin bullies,” he muttered and then he got ready

for bed. The rain had killed the sunset and dinner had

sucked so bad that he couldn’t even remember what it was

he hadn’t eaten.

“Tomorrow,” he said to himself, “tomorrow’s another day.”

Ebb, flow and click.

C.A. Seller

Art by Dan Reece