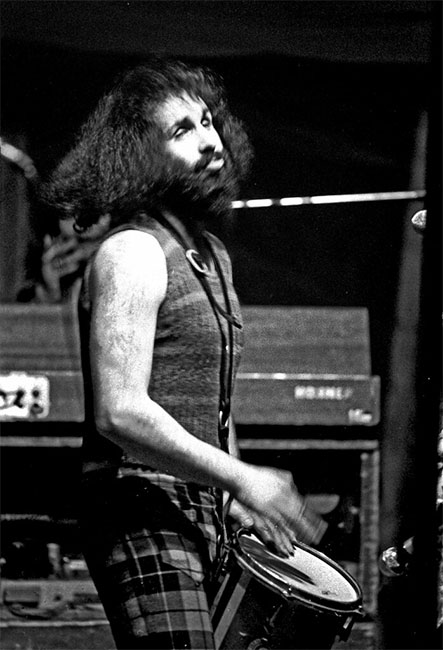

Pete Brown, a cult figure on the British poetry and music scene, has died, aged 82, after a courageous battle with cancer. He’s perhaps best-known for the lyrics he wrote for Cream, but he was also a leading poet and performer in his own right.

Brown’s parents were Jewish immigrants. His father changed his name to Brown to avoid anti-semitism. Driven out of London by the Blitz, the couple settled in Surrey. Brown was born there on Christmas Day, 1940. When he was 11, his parents moved back to London, where he was sent to a traditional Jewish school. He had a difficult time there and the experience left him with a negative view of religion in general. As he recounted in his memoir, White Rooms and Imaginary Westerns, ‘At that point I was a fully-fledged anarchist in so many ways. In so many ways I hated authority. There was a few of us at that school that kind of gravitated to each other. We were the outsiders.’ He started reading poetry (at first, Dylan Thomas and Gerard Manley Hopkins, later, the Beats) and, when he was 14, had his poetry published for the first time, in a US poetry journal.

Brown’s career as a poet began in the late 1950s. He soon found himself taking part in live poetry and jazz events with Michael Horovitz. He was one of the British poets who read at the landmark 1965 International Poetry Incarnation at the Albert Hall, alongside Ferlinghetti, Corso and Ginsberg. He also, around that time, formed a band, the First Real Poetry Band, in which he recited and improvised poetry to jazz. The jazz scene brought him into contact with Ginger Baker and Jack Bruce, who were, at that time, putting together the band that became Cream. He wanted to write some lyrics for them and went on to form a long-lasting songwriting relationship with Bruce. Together, they wrote several Cream hits, among the best known being ‘White Room’ and ‘Sunshine of Your Love’.

When Cream broke up in 1968, Brown continued to work with Bruce, writing many of the lyrics for Bruce’s solo albums. He also formed a band of his own, Pete Brown and His Battered Ornaments. He found himself not only writing the lyrics but having to sing them. The first album they made, A Meal You Can Shake Hands With In the Dark (1969), is arguably one of the high-points in Brown’s career. Sadly, the band he’d formed went on to sack him on the grounds that they wanted a better singer. Listening to the band now, one has to wish they hadn’t. The amalgam of psychedelic jazz, folk and blues they’d come up with was quite unique. Combined with Brown’s voice (yes, voice) and lyrics, the result was, in many ways, years ahead of its time.

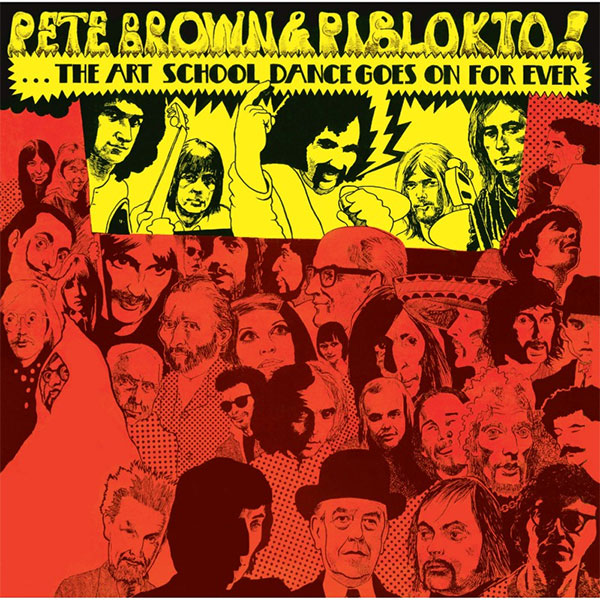

Brown then formed a new band, Piblokto! (the Inuit word for Arctic Hysteria). The jazz and blues elements were still there, but the sound was more rock-based than the Battered Ornaments. It went on to produce two albums. The first of these, Things May Come and Things May Go But the Art School Dance Goes On Forever (1970), met with considerable critical success. When Piblokto! broke up in 1971, he continued to be involved in a number of other musical projects. In 1973, he put out a mainly spoken-word album of himself reciting his poetry, The Not Forgotten Association.

Brown backed off from the music scene for a while in 1977 with the rise of punk, which is a shame, in a way. He was very scathing about punk. In this, I think, he was wrong: reading what he had to say about it, it’s easy to imagine poetry traditionalists talking in a similar way about the poetry he himself was writing in the 1960s. I can see there was a clash of sensibilities, but there was a raw energy to much of his poetry which was not a million miles away from the world of punk and the cultural changes that grew out of it. Fifteen of Brown’s poems found their way into Michael Horovitz’ 1969 anthology, Children of Albion: Poetry of the Underground in Britain. The spoof ad in one of these poems, ‘Slam (for Spike Hawkins)’, could’ve come straight out of an Alexei Sayle set:

RENT A CHOCOLATE BISCUIT

FOR ONLY £30 A DAY,

THEYRE SLIMY AND COMFORTABLE!

In the late seventies, Brown turned his attention to script-writing. He achieved some success in this, writing the screenplay for Felix the Cat: The Movie. He also co-wrote material for the Rolling Stones video, Rewind. Musically, he continued to collaborate with Jack Bruce and got back together with Phil Ryan, a former member of the Welsh band, Man, who Brown had performed with in Piblokto! (Brown had also put some percussion on a couple of Man albums). Brown and Ryan worked together up until Ryan’s death in 2015, issuing four albums: Ardours Of The Lost Rake, Coals To Jerusalem, Road of Cobras and Perils of Wisdom. They were great friends as well as collaborators. They were both on the left and many of their songs had a political edge to them. During that time, they co-managed two bands, first the Interoceters and, later, Psoulchedelia, to record and perform their work.

A lot of the work Brown did with Ryan has a soul/blues feel to it. (Listening to it, one is often reminded of something Brown said, that 85% of the musicians he liked were black). It’s easy to find oneself listening to Brown’s work over time, looking for some development of music style, when, in fact, what Brown was about was writing lyrics. He worked hard at his singing but it was always about the words and the collaborations he forged with musicians were always about the song-writing chemistry. The sound, the style, was an end product. That said, jazz (or, at the very least, blues) always had to be in there somewhere. How did he go about it? When he was working with Bruce, he generally produced words to fit the music, with Bruce throwing in the odd line or word. The result could be surreal and psychedelic or sometimes direct, as in ‘Politician’, written in response to the Profumo scandal:

Hey now baby, get into my big black car.

Hey now baby, get into my big black car.

I want to just show you what my politics are.

I’m a political man and I practice what I preach.

I’m a political man and I practice what I preach.

So don’t deny me baby, not while you’re in my reach.

I support the left, though I’m leaning, leaning to the right.

I support the left, though I’m leaning to the right.

But I’m just not there when it’s coming to a fight.

Brown recorded this song himself, with the Battered Ornaments. It might’ve been about the Profumo scandal, but it’s impossible not to listen to it without thinking of Westminster politicians today.

As the press release issued on his death states, Brown ‘lived the life of a warrior poet. He was proudly anti-establishment, and dedicated his life to his creative endeavours, in an uncompromising way’. He was involved in so many projects in the course of his working life, it’s impossible to mention them all. Some were very successful, others less so (he was always keen to give things a go to see where they led). In 2010, he wrote a memoir, White Rooms and Imaginary Westerns and in 2016, he brought out a collection of poetry, Mundane Tuesday and Freudian Saturday, his first since 1968.

Brown kept working to the end, co-writing a song for Joe Bonamassa’s recent album Royal Tea and with John Donaldson on their new album, Shadow Club. Earlier this year, talking to his biographer, Marc Shapiro, he said: ‘It’s been a busy year. So long as we can all stay alive that’s the main thing. I’m still here and I still have much to say.’ It’s a tragedy that he never got to say it but, I think, for a man with a creative drive like Brown’s, that never dimmed, never slowed down and which was forever adapting to circumstances, it was always going to end like that.

Pete Brown is survived by his wife Sheridan, his daughter, the writer and singer Jessica Walker and his musician and restaurateur son, Tad.

Dominic Rivron