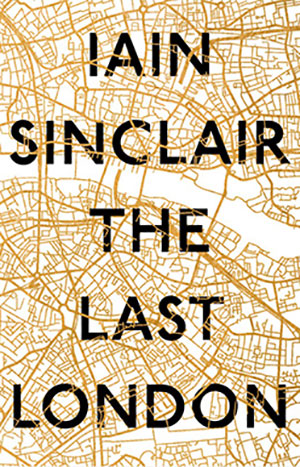

The Last London, Iain Sinclair (324pp, £18.99, Oneworld)

Blurbed as ‘a delirious conclusion to a truly epic project’, The Last London seems to be Iain Sinclair’s last words on the subject of London before he moves on to South Coast pastures and psychogeographical elsewheres. He’s had a good run, and if this book isn’t quite as marvellous as Downriver, London Orbital or Lights Out for the Territory it’s still packed full of intriguing information, verbal mappings, unusual histories and wry, social and political commentaries.

However, Sinclair does have a habit of ‘going off on one’, taking his prose and the reader away from his subject matter and through a tangle of asides, trivia and opinion before circuitously returning to his starting point. At times he attempts to give a frisson or significance to things that – truth be told – simply aren’t very significant or interesting. He even occasionally indicates that he knows he is doing this, that he is tired of speculation and occult meaning, that the London he used to inhabit and document is no more: hence the idea of the last London, not just Sinclair’s last words on the matter, but the city itself morphing into something new that is not what Sinclair knows as London or wants the place to be.

But in this last gasp, desperate to find what is left that he knows and to not totally let the new slip out of his grasp, he visits the Shard for an overnight stay and skyscraper swim, lurks in shopping malls and on the blurred edges of the capital (others have christened these the ‘edgelands’) and reminisces. Much of this book is an intertextual nod to his own previous writing and expeditions; the book is full of old friends, other artists and writers, as well as the expected rants against Brexit, the Olympic Stadium and the gentrification of the East End, and the more surprising outbursts against fashionable cyclists. (I should note that whilst it may be unexpected, this section is a comedic highlight.)

So inbetween the lazy pages of capitalized-and-run-together overheard conversations and the authorial asides there is classic Iain Sinclair. And if the book doesn’t quite cohere, and the camped-out solitary homeless stranger who fades in and out view in the book doesn’t quite work as a döppelganger for the author lost in the city, or as some kind of every/other-man, and if part of me thinks the book needed a bit more time and a harsher editor, it’s still a fine read, standing head and shoulders above the hordes of self-appointed psychogeographers who have appeared in Sinclair’s wake. Let’s hope it’s not the last we’ll hear from Iain Sinclair.

Rupert Loydell