‘PICTURES OF LILY,

MADE MY LIFE SO WONDERFUL…’

Society tends to be suspicious of pleasure. It’s a moral conundrum that western civilisation has never quite reconciled, one that occupies the dangerous twilight zone between the spirit and the flesh. Plato used the metaphor of a chariot pulled by two horses. The rational three-pounds of brain-matter between the ears is the charioteer, using the whip to attempt control, one horse is well-behaved, but the other represents our unruly, negative and destructive emotions. René Descartes, in a Christian context envisaged a division between a holy soul – capable of reason, and a fleshy body driven by ‘mechanical passions’. The dialogue goes from empirical philosopher-statesman Francis Bacon to social-positivist August Comte, from Thomas Jefferson whose Epicurean bias led him to declare ‘the pursuit of happiness’ an unalienable human right, to Immanuel Kant struggling with the concept of what is and is not real advocating ‘everything that is possible through freedom.’

Reason was privileged over emotion, until Freud appeared to seal the deal. To him, the rational ego’s mission is to restrain the animal instincts of the id. Sybaritic sensuality has a tendency to lead all too swiftly to debauchery. So the Puritans – and those of a similar mind-set, try to avoid it by banning fun altogether. With freedom, come attempts by nervous authorities to control those freedoms. And where exactly you place the limits of what is, and what is not permissible, is a clarity that has never been entirely resolved, and is always up for revision. Fashions in public morals come and go, but human nature remains reassuringly predictable when it comes to matters sexual and the politics of pleasure. As philosopher Jeremy Bentham argues in a wise defence of free speech, ‘as to the evil which results from a censorship, it is impossible to measure it, for it is impossible to tell where it ends…’ To the pure of mind, everything is pure. Filth is in the eye of the beholder. And me? yes, I have beheld…

Fact is, every civilisation is an experiment in moral values. An evolving attempt to balance differences within its structure. The ratios of power, class, and gender struggling, adjusting and fine-tuning against each other. Each civilisation is internally consistent, to itself, within the terms of its own definitions. If we assume that our values are more enlightened, more just and fairer than all the others, that’s probably because the values we value are our values. Objectivity is a tough one. There is no moral or societal strength that can’t – with equal validity and conviction, be seen as weakness. No liberalism that can’t be interpreted as decadence. And even within the same cultural continuity, decades have a tendency to jostle into each other, to act and react to each other’s emphasis. Periods of restraint open up into periods of self-indulgence, which then react into restraint again. What was once furtive, is now done openly. What was open, must now be done furtively. Learning from the perceived errors, and the apparent dangers of each condition. The repressed psychosis built up by denial is unhealthy: as are the contagions and social instabilities that result from over-gratification.

This way and that. Oscillating across years. From Cromwellian Puritanism to Restoration bawdiness. As early as 1660, just two years after Cromwell’s death, there are reports of Italian dildos being sold on St James’s Street. From Victorian and Edwardian respectability – via wartime austerity, to sixties Free Love, sex has been alternately glorified and vilified. ‘We know better than they did. We learn from their foolishness. We won’t repeat their blinkered blunderings.’ But doing it anyway. If the function of civilisation is to apply an element of logic and reason to human affairs, then sex is the great upsetter. The primal urge that thwarts all efforts at rational arrangements. And porn operates at the intersection of the two. The technology that makes its proliferation possible is the product of the scientific principles of reason. The viral message it carries is the disrupter of such values.

Freedom of speech includes the freedom to be vile. Yet, as a product of my time and generation, I persist in believing that tolerance is no bad thing. The West – so smug in its superiority over other less sophisticated cultures, has only relatively recently… in historical terms, enjoyed such liberal attitudes. Outside Christendom, Islam was conjuring Houris, sex lures to tempt and satiate male desires, pleasuring the pleasure centres of the brain. While Medieval minstrels sang paeans to love. But they also sang of daemon lovers, virgin-maids seduced and abandoned, and murder-ballads of marital intrigue. For marriage was essentially a union arranged by families with commercial or dynastic motives, specifically legitimising unfettered procreation within a structured family unit.

Human happiness is a simple, but revolutionary idea. It was Benedictine monk Gratian who introduced the novel concept of mutual consent for marital partners in his ‘Decretum Gratiani’, inaugurated into the canonical code of practice by the Council of Trent (1563), and laid out in Protestant theology by Thomas Cranmer in ‘The Book Of Common Prayer’ (revision 1552). And it was only much later, in 1836 that non-religious civil marriage was legitimised. The corresponding right of legal divorce – as distinct from something arranged by an Act of Parliament, was only passed into law in 1858, assuming a more liberal definition with the ‘Divorce Reform Act’ of 1969. To where the many quirks of individual satisfaction at last became more important than social and religious imperative. Although the underlying reality was very different, much of the ritual marriage symbolism remained – the transfer of ownership (and name) from father to husband. And the essential balance is still being tinkered with. 2005 brought Civil Partnerships for same-sex couples, and non-gender-specific marriage. Gay marriage followed.

But no. What I’m talking here is less exclusive, more extramarital and more democratic than that. It concerns those rare and carefully hoarded leather-bound editions to be consulted only by academics and historians that are now consigned to the British Libraries Secret Archive (the ‘Secretum’ established from Witt’s own aristocratic private collection). Aristocracy has always had its ‘eccentric connoisseurs’ of the esoterically exotic with their hidden stashes of erotic literature. Their interests have always been deemed ‘different’ to the hairy-handed lust of the common man, in some subtle way I’ve never quite been able to understand. They read Thomas Nashe’s (1567-1601?) witty Elizabethan poem “Choice Of Valentines” (or ‘Nashe’s Dildo’), the ‘prick-song’ about a young man’s loss of erection that opens with the florid ‘Pardon sweete flower of matchless Poetrie…’

As a poet and a kind of Elizabethan Mick Jagger, John Donne (1572-31 March 1631) started out as less metaphysical than physical, even corporeal in his reach. At a time when love poetry cloaked itself in a safe distancing of classical allusions he made his words directly personal. His elegy “To His Mistress Going To Bed” is so explicit it was initially refused license for inclusion in his posthumous collection, and only gradually reached an appreciative audience. Its lyrical striptease goes from ‘off with that girdle’ to ‘your gown’s going off such beauteous state reveals’ until ‘full nakedness, all joys are due to thee.’ It includes the lascivious ‘licence my roving hands and let them go, behind, before, above, between, below…’ (lines that anticipate twentieth-century modernism, and TS Eliot’s ‘exploring hands encounter no defence’ in the third section of “The Waste Land” from 1922). After his student carousing Donne married for love, which destroyed his career and for which he even did time in Fleet Prison. But the marriage endured until her death in 1617, giving birth to their twelfth child. Caught up in the fierce religious schism through which his family had suffered exile and martyrdom, he tactically switched from Catholicism to become a Protestant, and later even wound up as Dean of St Paul’s. But we can forgive him that lapse for the sensual realism of his early verses. As Van Morrison writes, ‘roll on John Donne!’

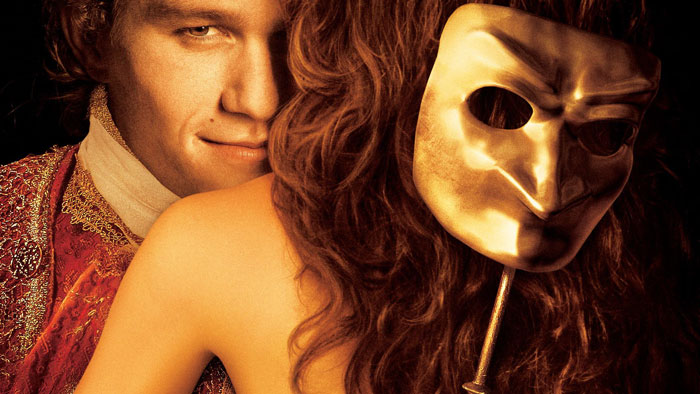

Then there’s the promiscuously bisexual second Earl of Rochester (1647-July 1680), who could wittily boast of his debauched life-style in underground manuscripts that document the doomed trajectory of his career as soldier, wit, satirist, poet and self-destructive reprobate. During the ‘hang-over’ of the Restoration Monarchy the Earl – real name John Wilmot, celebrated as ‘The Libertine’ (2004) in the Johnny Depp movie, was a whoring, wine-swigging seventeenth-century courtier, with a recklessly determined honesty for ‘bone-hard medical fact’. He was a perverse poet of filthy four-lettered verse that still stands as the most celebrated of the period. His “A Ramble In St James Park” chronicles all manner of perverse al-fresco goings-on. His “Satyre On Charles II” claims that the monarch’s ‘sceptre and his prick are of a length.’ A scourge of polite society, such flagrantly bawdy satire led to his brief exile. The line ‘I am the cynic of our golden age’ may have been spoken for him by Johnny Depp, and contemporary paintings suggest little of Depp’s wickedly mischievous charisma, but it does seem to capture the essence of the man.

Although he married Elizabeth Malet, the Laurence Dunmore screenplay revolves around his relationship with his mistress Elizabeth Barry (played by Samantha Morton), the actress he tutored. According to Samuel Johnson, Wilmot ‘blazed out his youth and health in lavish voluptuousness.’ With an epicurean’s taste matched to a glutton’s appetite, he drank to excess, disported with mistresses and prostitutes and, perhaps inevitably, died young, probably syphilis-ravaged in Woodstock. His “Sodom, Or The Quintessence Of Debauchery” remained suppressed until long after his death. Graham Greene wrote a fine biography of him, and although completed in 1934 it too was not published until 1947 for fear of prosecution for obscenity!

The chaotic and seething metropolis of Georgian London was a booming mass of some 700,000 people. Yet from erotic fiction such as ‘Fanny Hill: Memoirs Of A Woman Of Pleasure’ (1748) to the saucy drawings of Thomas Rowlandson, the libidos behind the petticoats and breeches, crinolines and corsets of eighteenth-century Britain were somewhat less than controlled. Prostitution was not illegal, and there was something like 50,000 people employed at various levels of the paid-for sex-trade. Hogarth’s line-engravings illustrate life and death in the streets around the taverns and coffee-houses of Covent Garden, showing a ‘clapped-out prostitute’ – i.e. a victim of the clap, dying of syphilis with predatory quack-physicians hovering, exploiting her with ‘mercury’ cures.

His perceptive art captures and accurately skewers the iniquity and hypocrisy of the time. From the sophisticated up-market Pall Mall ‘Nunnery’ pleasure-dome brothels – where madam Mrs Hayes was so successful she amassed a £20,000 fortune for her retirement, to the more downmarket ‘trugging-houses’, and the ‘Molly-Culture’ of brothels where ‘effeminate sodomites’ acted out wedding ceremonies and pregnancies, even giving birth – in a surreal twist, to hunks of cheese. Where streetwalkers could tempt the likes of diarist James Boswell to an outdoor coupling on the newly-built Westminster Bridge, and such an encounter could be had for sixpence. While a night with a high-class courtesan would cost six guineas. Lists advertising and evaluating the services of women of the night were widely circulated – including ‘The Whoremongers’ Guide To London’, and the most celebrated of them all – ‘Harris’ List’, which debuted in 1757 priced at 2s 6d, and stayed in print for thirty-eight years, regularly updating contact information concerning the ‘Covent Garden Ladies’. Credited to Jack Harris, its origins were less straightforward. The impetus came from pimp-general John Harrison, utilising his extensive contact-lists, but it was ghost-written by Sam Derrick. Harrison eventually spent time in Newgate Prison for his pains, but his work survived.

Other offenders were brought to the censorious attention of the ‘Society For the Reformation Of Manners’ precisely because it was catering – not only for slumming aristos, but for the working-class, and Gays too. So an entrapment operation at ‘Mother Clapp’s’ bawdy-house led to a February 1726 Police Raid, resulting in three victims being publicly hanged for the heinous crime of sodomy, while Mother Clapp herself was literally pilloried – enduring public violation and humiliation in the stocks, following her own July 1726 trial.

The moral backlash of the 1850s saw further crackdowns on what they saw as more blatant excesses, from targeting the taste for bawdy books, to establishing strict religious ‘Magdelene Houses’ intended to wean whores off vice, and even to the extent of moral reformers placing fig-leaves on naked statues. Giant leaps for cleanliness and godliness made by philanthropists and busybodies, the great moral and social crusaders of industrial Britain, sometimes spurred on by the concern that if the populace doesn’t mend its disgusting ways it’ll catch something nasty off the French. Such as revolution, egalitarianism and the butchering of the propertied classes. The ‘London Journal’ (for May 1726) was even vigorously and enthusiastically recommending castration for ‘deviant’ Sodomites. The social truth is that wherever opulent wealth resides side-by-side with extreme squalid poverty the lines of commerce between the classes will inevitably include sexual opportunism and exploitation. As Fanny Hill points out, ‘virtue is better than vice, but we can’t always choose.’

John Cleland was born in September 1710, spent a well-connected childhood in St James’ Place, and was educated at Westminster School. He signed up as a seventeen-year-old soldier and set out for Bombay (Mumbai) to seek his fortune, transferring to the East India Company. The venture was brought to a close by his father’s death, and he returned to London in 1741, to find himself in reduced impoverished circumstances. Worse was to come, and he was sent to the decrepit Fleet Debtors Prison for 376 days for an outstanding sum of £800. It was during this period of incarceration that he wrote his notorious ‘Memoirs of a Woman of Pleasure’. As writer Tony Rennell observes, ‘in our mind’s eye, we can try to imagine the middle-aged Cleland at work, finding a quiet corner amid the squalor and mayhem of the prison yard and for a year scratching out with a quill pen the extravagant prose and the indecent exploits that would make him famous.’ His heroine – ‘Fanny Hill’ is a naïve country girl who makes her fortune selling sex in the brothels that abound in the metropolis. By the end of the first dozen pages she’s been lured into the sex trade by a brothel-owner and initiated into Sapphic pleasure by another of the girls ‘whose lascivious touches lighted up a new fire that wantoned through my veins.’ She should, Fanny admits, have ‘jumped out of bed and cried for help against such strange assaults,’ but she didn’t. ‘I was more pleased than offended.’

Filmed for the umpteenth time in 1983 by director Gerry O’Hara his version of the saucy long-banned classic features Lisa Raines as the fifteen-year-old ingénue moving into eighteenth-century London to become easy – and willing prey for the sophisticated city toffs. After suave Jonathan York woos and then dumps her, Raines’ idea of revenge is to sleep her way around town. It’s a poor romp that wastes the talents of Oliver Reed, Wilfred Hyde White and Shelley Winters. It later became a superior BBC4-TV two-parter midwived by screenwriter Andrew Davies (from 31 October 2007) with Rebecca Night as the new incarnation of Cleland’s ‘happy hooker’, prompting writer Tony Rennell to investigate its fully detailed history (in ‘The Daily Mail’ 10 October 2007).

Taking his cue from imported risqué French literature, Cleland had announced his intention of writing ‘the truth, stark naked truth’ even if that means exposing ‘unreserved intimacies’ and ‘violating the laws of decency.’ Written with eye-watering detail from his heroine’s point of view, the narrative portrays female sexual feelings with intimate knowledge of the whore’s seedy subworld with a playful sense of authenticity Cleland could never again recapture. It was an unusual accomplishment that suggests that perhaps he had ample experience in the field, by way of research? The first 750 print-run edition from Fenton Griffiths was advertised in a London newspaper dated Monday, 21 November 1748 as ‘this day is published Memoirs Of A Woman Of Pleasure’, priced at three shillings, its author identified merely as ‘A Person Of Quality’. Perfect for those who like their wenches saucy, their ragamuffins filthy and their libertines insatiable. Soon its success bought his freedom by becoming the first commercially-published work of British erotic fiction.

Bishop Thomas Sherlock denounced the novel from the pulpit. A minor earth-tremor in 1750 toppled London chimneys and felled old buildings, it was interpreted as evidence of god’s disapproval. Within six months – first the publisher, then Cleland himself – once identified, was re-arrested on obscenity charges, and – terrified of enduring a return to jail he disowned the book. He squirmed and counter-claimed, he even denied having written the work, which was out there ‘corrupting the morals of the king’s subjects.’ He’d merely edited the work of an anonymous ‘young nobleman’. Later still he confessed to diarist James Boswell that yes, it was his own work, but no, he’d written it as a youth and only sought publication when he was broke and desperate for get-out-of-prison-fast cash. Yet another possibility, suggested by Cleland’s biographer – William Epstein, is that he was merely writing down a kind of popular urban myth that had been circulating for many years.

Whatever the truth, he escaped with his liberty, but ‘Fanny Hill’ was subsequently available in only an expurgated edition. Suitably chastened, but lured by the prospect of respectable literary success the experience had so tantalisingly promised, he set to work producing more books. A male counterpart to ‘Fanny’, ‘Memoirs Of A Coxcomb’ (1751) lacked both its predecessor’s saucy page-turning content, and its success. As did his three-volume ‘The Woman Of Honour’ (1768). Moving on to plays he unsuccessfully pestered David Garrick to stage one of his three works, including a pseudo-classical ‘Titus Vespasian’ (1755). Then, while contributing scathing grumpy-old-man tirades about the declining standards of society to ‘The Public Advertiser’, and despite his lack of training, he wrote a set of quasi-medical journals. He died a bitter and envious malcontent in 1789, still infamous for the one book of erotica. It remained suppressed for two-hundred years, circulating in underground editions sold under-the-counter, a titillating open secret among the posh, literate classes. Even Mayflower Books were prosecuted for bringing it back into print in 1964, and it was not until the 1970s that its prohibition was finally repealed and its ‘classic’ status confirmed by Penguin and Oxford imprints.

‘Fanny Hill’ was but one of many books in a well-populated marketplace of what Bishop Sherlock denounced as ‘the histories of the vilest prostitutes,’ third-hand accounts of the lives of courtesans and ‘whore biographies’ – or, in the vernacular of the time ‘bunters’, ‘punchable nuns’ or ‘trugmoldies’, that sold in prodigious number. Real-life divorce proceedings were instantly turned into erotic entertainments with titles such as ‘The Cuckold’s Chronicle’. Caught up in the delicate play between permissiveness and morality, the pretence – or perhaps even the fact of being genuinely troubled by the fate of the falling or fallen women, stalks through the novels beginning to emerge from Richardson and Fielding, to Defoe’s ‘Moll Flanders’ (1722).

Operating very much as part of the same process, they protest their right to depict such characters as part of an urgent moral debate. They were intended to be moral lessons, unlike the richly amoral boldly unrepentant Fanny, even though Cleland’s cracking good-read uses inventive prose, comic euphemism and florid metaphor in place of more directly explicit terminology. Fanny’s greatest sin is that she pursues sexual pleasure with joyful abandon and élan. Every man is hugely endowed, every woman a willing participant. And worse still, she ends up prosperously and contentedly married to her forgiving long-time love. The common reader, as distinct from the academic dilettante, must be protected from such aristocratic deviance. Perhaps, like the licensing laws themselves, such literary distractions were intended to be kept away from the masses lest they interfere with productivity?

It was different, by degrees, on the Continent. In Venice, for example, as recounted in the amorous ‘Histoire De Ma Vie (The Story Of My Life)’ of Giacomo Casanova, the man long-renowned as the world’s greatest lover. Born 2 April 1725, it has been estimated that – give or take a ménage à trios, he notched up some one-hundred-&-thirty conquests before winding up as librarian to Count Waldstein of Bohemia, where he relieved his boredom by recording them all in the twelve volumes of his notorious memoirs. Surprisingly he’d begun by studying theology as preparation for the priesthood, then gained legal qualifications at eighteen, shortly before losing his virginity. As well as being a lover and prodigious traveller, he was also a prolific author of fiction and philosophy, a connoisseur and cabbalist, a student of medicine and an accomplished musician, but it’s as a sexual adventurer that his name has become part of the vocabulary. Another to give his name to a branch of sexuality – The Marquis De Sade, shared the same time period. Casanova died in 1798, De Sade in 1814.

The turn of the decade into the 1750s marked a general turn-around in the moral climate, and the tightening-up of censorship. William Wycherley’s deliciously ribald Restoration comedy ‘The County Wife’ – an anti-Puritan work full of lewd innuendo, the story of a rake who convinces everyone that he is impotent in order to gain free access to their wives, was controversial in its day, it was banished from the stage in 1753 – and remained unseen until its twentieth-century revival. It was a period that marked the decline and fall of ‘John Bull’, that free-born, free-living, roistering libertarian, a character whose demise was guaranteed as the country underwent the transformation from the agrarian-based society to an industrial one. Bull’s downfall was hastened by the rise of the urban middle-classes who conveniently forgot from whence they’d sprung and their bourgeois desire to extirpate what they perceived as the moral turpitude of the underclass.

From that middle-class viewpoint, there seemed certain grounds for concern. According to the 1811 census there were no fewer than 49,500 licensed taverns in the UK, a figure which constitutes one house in forty-five. Naturally, many such premises doubled as gaming houses and brothels. Not to mention cesspools of debauchery, horseracing, gin-drinking, pox, bad manners and such activities as bullock-baiting – in which the unfortunate beast would have its ears blocked with peas and its body pierced with iron rods. The enraged animal would then career down the street harassed by a baying mob, thrilled by the havoc it wreaked. Such activities were not deemed fit for what the great and good considered appropriate for a civilised country.

They might have had a point, but the new Puritanism, driven by Whig reformers, evangelists and philanthropists, as concerned with self-aggrandisement as morality or benevolence, gradually enforced a new code. Society, rather than the individual, became paramount, the pursuit of pleasure was replaced by the work ethic. Nowhere was this more evident than in the behaviour of the nascent Metropolitan Police. This was supposed to be a force that would dispense even-handed justice. In practice, it was used to clear the streets of those dubious types respectable people deemed undesirable. Britain became undeniably a more sober, prosperous and hygienic country, but in the process, it lost something of its gaiety, spontaneity, exuberance and delight in good living and plain speaking. As Leigh Hunt wrote in 1825, ‘we were to show our refinement by being superior to every rustic impulse and do nothing but doubt and be gentlemanly and afraid of committing ourselves.’

The ‘Age of Reason’, alternately called ‘The Enlightenment’ was a period of intense intellectual excitement, a time when people began to feel they had the ability to understand and – through understanding, take control of the world. The tools to achieve it were not divine revelation or dull dusty dogma, but bright-eyed intelligence, reason and science. Human beings could be the architects of their own fortunes. The world and its corrupt institutions could be rebuilt in accordance with the principles of rationalism. This was well-before the material limitations and human fallibilities would become apparent. For ‘science and prurience proceed hand in hand’ as Linda (author of ‘Hard-Core’, 1989) Williams points out. And it is the gradual expansion of technology keeping pace with the growing market for images that redresses the situation. A perfect fusion of commerce and culture.

Earl Stanhope replaced the old wood-frame printing press with a more rigid iron model in 1803, enabling faster and more efficient print production. But it could be a weapon of subversive social change too. The French Revolution allied porn with libertarian propaganda to attack Church and Aristocracy, explicit wood-engraved cartoons of ‘Austrian bitch’ Marie Antoinette copulating with all and sundry, were used to destroy political reputations by accusations of sexual degeneracy (as in Monica and Clinton!). In its earliest phase, before it turned in on itself and devoured itself, the revolution had set its course against every aspect of irrationalism. Intent on reconstructing the world through ‘Reason’, according to Jean-Jacques Rousseau’s concept of ‘social renewal’. It’s worth recalling that analysis and experiment was also the chosen route favoured by Mary Shelley’s most famous creation, Baron Von Frankenstein, formulated by the Geneva lakeside on 14 May 1816.

BY ANDREW DARLINGTON