CHAPTER ONE: ‘MY LIASONS PORNOGRAPHIQUE:

A DOCUMENTARY OF MY LIFE AND HORMONES…’

‘If you took all the girls I knew when I was single,

and brought them all together for one night,

I know they’d never match my sweet imagination…’

(Paul Simon – “Kodachrome” 1973)

To point out that the statistics of male violence against women is terrifying is to state the obvious. Even leaving aside, for the moment, the infliction of female genital mutilation and forced underage marriage, people-trafikking for prostitution purposes, the deliberate and systematic repression of gender rights through the guise of religion and culture. If, for sake of argument, we simply restrict the scope to the suposedly liberated emancipated West, to the U.K alone, 85,000 women have experienced rape, attempted rape or sexual assault by penetration in England and Wales alone, according to the Crime Survey for England and Wales (CSEW), and over 400,000 women have been sexually assaulted in England and Wales, according to Home Office figures. One in three teenage girls have experienced some form of sexual violence from a partner, according to the University of Bristol (for NSPCC), and one in five women has experienced some form of sexual violence since the age of sixteen. According to the U.N, 137 women are killed by a family-member every day. On a global scale, during 2017 it was estimated that of the 87,000 women intentionally killed, more than half (50,000) were victims of intimate partners or family members, with 30,000 killed by current or former intimate partners.

Statistics are numbing. My story was not written without considerable pre-thought and some degree of trepidation. It is – as the title suggests, a personal history. And hopefully the dialogue matures as it continues and evolves. But the essential motivation is honesty. There is a great deal of denial and pretence in matters of gender balance. And to simply ignore the more unpleasant aspects of male sexuality is worse than counterproductive, it can be dangerous.

There are a couple of personal examples that spring to mind. When I was a young print apprentice I was working with some older timserved tradesmen, all respectable married men with families, who had served during World War II. He wore blue boiler-suit overalls, and smoked hand-rolled cigarettes. But there was one story he told me that horrified me in particular. He was part of the army fighting their way up through Italy, and he spoke in quite a matter-of-fact way about how the Italian people in the area were going through such extreme privations that ‘you could get a woman for a tin of bully-beef’ because they were starving and needed to feed their children. This man was not a creepy pervert. He had sisters, a wife and daughters.

We live in insulated times. Take people outside our safe civilised continuum, and the beast is lurking. Remember those clean-cut all-American males from Smallville USA who were drafted to Vietnam… and picked up ‘comfort girls’ at gunpoint during their patrols into the badlands?

I asked a friend called May about the small scar on her throat. She told me how a former partner had gripped her around the throat so violently that a locket she was wearing was driven deep into the soft flesh beneath her skin. These are the nightmares that haunt and terrify me.

I was going to say there’s a darkness at the core of the male soul. But to say ‘darkness’ is to place it within a moral spectum. And morality is an artificial construct erected long after the advent of the act. This is a primal thing. We ignore it at our peril. Hopefully, through honest dialogue we can confront and attempt to understand these unpleasant truths. And to do it with some degree of humour.

Sorry to bore on at this uninvited length…

— 0 —

Ladies and Gentle-Beings, I have a dream. And it is a wet dream. What follows is a documentary of my life and hormones. It is also the story of repeated furtive encounters with ‘The Beast With Five Fingers’. It can be argued that onanistic proclivities are our oldest and best-loved self-indulgence. It can be argued that the filth impulse is etched deep into every DNA-strand of our genetic code.

Horn of rhino. Penis of tiger. Root of sea-holly. Husk of the emerald-green blister beetle known as Spanish Fly. Tab of Viagra. Aphrodisiacs come in many guises. Few are as potent as female nudity to a pubertal male. Of course, we are only organisms reacting to stimuli. Girls can’t help being beautiful. But they are. They don’t necessarily ask to be desirable. But they are. It’s not their fault. Just as it’s not a male fault for reacting that way. It’s just stimulus. Chemicals.

How often do you think about sex? Only once. But chances are you’re still thinking about it. And when did zis all begin? The sexual impulse, to John Lennon, is reaching for ‘the other side of the sky.’ The root of the root, the seed of the seed, the bud of the bud. In Ted Hughes “A Childish Prank” from his poem-cycle ‘From The Life And Songs Of The Crow’ (Faber, 1970) sex is a malicious joke invented while god was sleeping. ‘Crow’ interferes in sexless Eden by biting a worm into two halves, stuffing the tail onto man ‘with the wounded end hanging out’, and plunges the other headfirst into woman where it calls out to its tail-half to re-unite, ‘join up quickly, quickly, because – O – it was painful.’

There are other creation myths that poetically describe the origins of gender. Doris Lessing conjectures her own in her novel ‘The Cleft’ (Harper Collins, 2007). Originally, in the society she envisages, there are only females, known as Clefts, who spend their time lounging in the sun and occasionally spontaneously give birth. Then, disturbingly, males start to be born. These they call ‘monsters’, and they’re left to die. Rescued by eagles they establish their own community, eventually joining forces with some of the more radical Clefts. Lessing’s perfectly weighted sentences craft the beginnings of gender politics, with the ‘monsters’ portrayed as rash and inquisitive, the clefts circumspect and caring. Both endure lots of issues with each other in a continuing template for humanity.

If it achieves nothing else, at least it provides a charming riposte to the Judaeo-Christian myth in which woman is no more than some sky-god’s afterthought, generated from Adam’s rib for the express purpose of being his companion. Although even there lurks the shadow of Lilith, a deity remaindered from yet earlier times, and subsumed into areas of belief as Adam’s first wife. The wilful assertive first wife who refuses to lie beneath him to copulate, and is punished for her insubordination. Replaced in the texts by the more submissive Eve, a temptress of a more controllable hue.

After all, the Y-chromosome that defines maleness is essentially an X-chromosome with a little bit missing. The female anatomy is the species’ default setting. Regardless of your creation myth of choice, as part of a species consisting of two genders, we are destined to a naturally fractious equality of mutual need. Except – of course, that like train-lines tapering away into the distance, what man wants from woman, and what woman wants from man, may seem to exquisitely merge into a pleasing oneness at the point of horizon – but that is just an illusion of perspective, in actual fact the discrete separation will always remain a constant.

Why is there beauty? A simple enough question. But one we take for granted.

Why beauty? Is it nothing more than reassurance built up through familiarity? Sky, grass, trees… the shoreline of water. The signifiers of the landscape within which we grow, and built up though successive memory-layers of days, weeks, months and years, until we embed ourselves there. The soft curves of human body contours because that is our first awareness as a separate organism, a source of sustenance, comfort, warmth, survival itself. And all our appreciations of form grow out of the imprinting of those first impulses. Can it be as simple as that?

The study of human origins interprets the advent of the conceptual ability of symbolic thought as a giant leap in human evolution. One that set our species apart from the rest of the animal world, and on the road to – more or less, where we are now. The ability to let one thing represent another in the mind, and in representation. Cave art. Images. Therefore, the act of looking at, and interpreting printed illustrations is part of what makes us human. Relating a flat two-dimensional arrangement of shapes, lines and colours on the page to a real three-dimensional moving organism in the real world is a high-concept achievement in anthropological terms. Deciphering texts is another cultural step, being empathically and emotionally affected by squiggles on paper is something else that defines us as a unique species on this planet. As you’re reading this – congratulate yourself, you’re doing something that’s pretty incredible. This is no small detail. This is a big issue.

That this unique ability can cunjur bad ideas as well as positive ones is an integral part of the package. Why do bad books exist? Basic Free Market theory suggests that products find their own sustainable level. That where there is a viable market, there will be answering products. Where there is sales potential there will be enteprenaurial motivation to fill the need. Of course, the same argument can be used to justify a trade in heroin. Society has an inbuilt bias towards control of what consensus opinion determines to be damaging. It’s where the division between the two is drawn that things get lively.

It must have been simpler before the invention of language. The mating urge is basically uncomplicated. The biological imperative to procreate. A thing of fecundity and reproduction. A grunt. A copulation. The transmission of the selfish gene. Individuals die. Sex provides a kind of immortality. Some of the earliest forms of crafted art represent the ‘Earth Mother’, Paleolithic figures estimated as carved 24,000–22,000 years ago – such as the ‘Venus of Willendorf’. They show the female form reduced to its essential reproductive function. Wide hips, within which life is conceived. The vagina through which the child enters the world. And breasts that nurture the young into survival. Fertility. Fecundity. That’s about it.

When it comes to objectification of womakind, things don’t get much more direct. But human’s being human, this is part of a tendency to conceptualise it, abstract it, idealise it. First premeditated, anticipated… then, afterwards, analysed, rated and considered. A tendency from which all the world’s greatest romantic fiction, poems, movies, art and love songs are spun, rehearsing and interpreting the infinite varieties of love. And their more scurrilous variants perform the same function for the sex act itself. For in such a context, sex is infinitely more than strictly functional. Animals groom each other in intimate group-bonding. Sex is that too. It is tactile comfort with a regular mate. The more physicality, the greater the enduring pair-bond. The stable structure for raising the resulting brood. But the bio-lottery maximises through diversification of the gene-pool too, hence a bias to multiple copulation with more than one partner. Which blurs the definition of what is and what is not ‘natural’, even in non-humans.

The truth is, regardless of what experts tell us, no-one alive today can be truly certain of what carvings such as the ‘Venus of Willendorf’ represent. Objects of veneration – almost certainly, these things were the result of skill and applied technique. But that they could also be vulgar and crude is only a contradiction from the point of view of subsequent belief-systems, those that amputate the physical from the spiritual. Those that steal the messy procreative wisdom of the womb and substitute it with something altogether more tenuous. It’s likely, back then, there was no such division. It was a single woman-centric continuum with the mysterious and profound power of reproduction at the core. An ‘Earth Mother’, rather than a Holy Father.

Clothes are interesting too. As a phenomenon. People are the only animals that wear clothes. Apes don’t wear clothes, except on TV. At some evolutionary stage our mutual vertical primate ancestors must have diverged into clothes-wearing humans and non-clothes-wearing naked apes. It obviously provides an evolutionary advantage when early humans emerge up from Africa into less hospitable ice-age climes. A clothes-wearing predisposition would prove useful when colonising chillier terrain. But it seems to me that bodily decoration came before the more practical necessities of apparel. Face-painting, necklaces of shells, feathers, and small bones.

For us, our bodies are smothered away in clothes literally from the moment of birth until it’s impossible for us ever to recapture that original state. Contrast it with the Amazon tribal girl smiling out of the pages of ‘National Geographic’ wearing just a necklace. She’s entirely unselfconscious about her beautiful nakedness, and body-unaware that she’s the focus of sweaty wonderment to schoolboys thousands of miles away in Yorkshire. Naturism is a determined attempt to revert to a more natural unclothed condition, but by necessity it’s done with the kind of deliberation that our social conditioning forces upon us, so that it loses all spontaneity. It is not so much natural as a determined contrary statement in itself. And because it is preconceived, conceptualised, intellectualised, done at this place and time and not in that place and time, it can never recapture that true innocence.

Once clothing becomes the norm, religions and moral conventions move in to fetishise what can and what cannot be revealed. And the very act of concealment raises curiosity about what is concealed. We are an inquisitive species. That’s how we’re wired. Whatever the original motivation for covering up certain parts of the body, by doing so it invites questions about what lies beneath. Writer Michael Moorcock creates an alien race for comic effect (in his ‘Dancers At The End Of Time’ sequence), to whom elbows are the focus of prurient interest. Which results in a whole new category of inventive taboos, and taboo-breaking. Just as women in veiled societies contrast with unveiled ones. The naked face can be as freighted with social implications as the naked breast.

And it is within those interstices, that fantasy and imagination provide the virtual points connecting the two. As Romantic Poets reinvent the object of their idealisation into something that more approximates their flawless ideal. As ‘Mills & Boon’ romances replicate entirely unreal male protagonists that will exist solely to meet female expectations. And Porn… which also exists somewhere in the war-zone between the two. Charles Lamb, the Romantic Poet knew something about it, he said ‘there is no law to judge the lawless, or canon by which a dream may be criticised… we do not know the laws of that country.’

If words and images on a page have the power to make those feelings real, Newsagents have known it for years. All tall people are wankers. Comedian Jack Dee said that. Their Top-Shelf specialties are magazines designed to be read in the privacy of one’s own bathroom, copy of ‘Knave’ in one hand, libido in the other, lubricating the flow of what ‘Dr Strangelove’s General Ripper calls those ‘precious bodily fluids’. It’s just that as soon as you’ve devoured one, you’re already looking forward to the next, with damp underpants and warring hormones.

The history of pornography is an alternative history of world-literature, with its own irresistible momentum. Chinese Emperor Huang-Ti reputedly wrote the world’s first sex manual 4,500 years ago. Since then, nested inside the main narrative like Russian Dolls are miniature histories of passing eras painted in vividly garish detail by grubby forgotten hacks. Writing make-believe and nonsense in secret, published through pen-names, paying the bills through forbidden writing, and yet they died, more often than not, in anonymous penury.

— 0 —

According to pop-mythology, somewhere between post-war austerity and Woodstock, copulation went public. According to poet Philip Larkin, sex began in 1962, between Lady Chatterley and the Beatles’ first LP. He’s wrong, of course. It happens in every life around the time raging hormones go into meltdown. Puberty is the time when every daydream turns to some aspect of sex. And the object of its pruriently grubby interest invariably comes in unexpected guises. Sex is not only an important part of adolescence. It is adolescence. The arrival of pubic hair and its attendant potential is like placing a hand-grenade in the hand of a baby.

Puberty is a kind of glandular lyncanthropy that transfigures you and brings on uncontrollable bodily metamorphosis. Devolving you into a hairier repository of more bestial urges. Welcome, it says, to ‘This Spurting Life’. Suddenly I get itchings in places that ‘Dan Dare’ can no longer reach. Jupiter, the hugest planet in the solar system, has a massive force of gravitational attraction. But that’s nothing compared to the gravitational attraction of a pubertal boy towards that biological circus in his underpants. When the biological equipment (the wet-ware) comes online, it’s the shiniest most excitingly pulse-pounding thing you’ll ever be gifted with, yet the law forbids you to plug it in. Even later, when the ‘age of consent’ ushers you in (and even that varies according to where you live and on the basis of your sexual proclivities) there are still going to be socially coercive pressures there to ration you. The need for fidelity, monogamy… cash, opportunity. Writer George Simenon – creator of Inspector Maigret, claimed to have slept with a thousand women. In a single lifetime, that seems a lot. On a global scale, infinitesimal. And you burn for them all. For their beauty, their softness, their entrancing otherness.

There’s the telling joke about the man who goes to the Doctor with an ‘embarrassing sexual problem’. The Doctor suggests he talks through the activities of his average day. So the man explains. He begins the day with a vigorous bout of morning sex with his wife before getting up. Later, in his office, he has elevenses sex with his personal secretary before his regular lunch-time assignation with a call-girl in a massage parlour. In the afternoon he has another desk-ender with his secretary before an after-hours evening meeting with his mistress for sex in his car, before returning home for bed – and late-night sex with his wife. Yes – says the Doctor, but what exactly is the problem? Shamefaced the man admits ‘I think I’m masturbating excessively to an unhealthy degree.’ See? No matter how fulfilled your sex-life, you want more. You want to love like a man. Love all you can. And, largely speaking, you can’t. No matter how many you love, there will always be so many million others you haven’t, won’t, can’t love. And you ache for each and every one. So what can you do? No matter how extensive your sex-life, there’s still a role for fantasy.

I read. I always have. I read everything. It’s a compulsive behaviour pattern that began early, and continues through a life-long scavenging in second-hand bookshops. Reading creates a field of play for the imagination. Science Fiction takes you into other realms, other times, alternate states of being. Erotic fiction can do that too. But it only goes so far, it’s up to you to fill in the rest. It can create virtual places in which you can find ways of exercising your achingly under-used muscles, but they are places within planes of experience increasingly detached from reality. George Eliot called her novels ‘a set of experiments in life.’ More downmarket prose can serve much the same function. For poet Edward Thomas it is the intellect that separates us from what is real – for the intelligentsia ‘ideas are in advance of their experience,’ in other words, they think before they do, while ‘their vocabulary in advance of their ideas,’ that is, they talk before they think.

The 1950s was a sad repressed conformist somnambulistic decade. At the time – which more or less coincides with Larkin’s equation, other short-trousered adolescents in similar rites of passage were apparently having real sex, and not just with themselves. Or even with each other. But if you can’t have sex in bed, you settle for sex in the head. And instead, my Mother’s mail-order catalogue of female underwear and lingerie, or the ads for bra’s and corsets in ‘Woman’ or ‘Woman’s Own’ become an instant sexopedia with trouser-troubling tendencies deep within the baggy deformity of school grey flannels. Such magazines can conjure eroticism – and the resulting genital gymnastics, out of the most unpromising material. They ease the hormonal gymnasium of growing pains, each encounter inducing Repetitive Strain Injury to the wrist. Because hey, when the equipment comes online, it’s essential to try it out, even if the only venue available is the virtual reality illusion of soft-core fantasy worlds. Pity they don’t come with Stain Digesters.

Of course, girls are also caught up in their own – even more devastating, puberty tail-spin, phased to cycles of the moon, but such are your self-absorption levels that you easily ignore everything else out of existence, beyond your own unique centrality to the universe. Doomed to its pain. Its existential isolation. Trapped by your defensive malevolence and personality flaws. Pernicious puberty is busy making a Clearasil nightmare of your face, and a crusty facial Vesuvius is a major passion-killer. It’s busy adding new elements to your deranged physical oddness, your evolving body-form which has already been forced through more changes in your first decade-and-a-half than it will throughout the rest of your life. Women seem to be romantic rarities, rich, exciting and strange, a feeling I’ve never quite recovered from…

Why this emphasis on adolescence? Why this preoccupation with one particular stage of life? In his wonderful autobiography jazz-man Miles Davis writes about how every heroin-addicted junkie is endlessly striving to recapture the pure elation of their first hit, escalating the doses with diminishing returns. Sex is a similarly addictive habit-forming habit. Orgasm releases a dopamine-oxytocin high. A kind of heroin-hit. And first cuts are deepest. And long-term fetishisations can be similarly implanted by first exposure. There are theories concerning this. If you’re a Freudian, it’s a no-brainer. Which is why the corruption of innocence is so dangerous, and can have life-long repercussions. A long-term attachment to a particular type of feminine underwear can be imprinted by the heightened erotic charge of a furtive first glimpse. Or an aroma associated with a first experience. Or a sex act in itself, which constitutes part of an initiation, can establish a life-pattern. Like a junkie forever attempting to recapture that first thrill. So it’s something to be treated with care.

Jorge Luis Borges once described books as the most astonishing of all human-devised instruments. Other technologies are brought into play to augment limbs or organs, tools fortify the arm, the microscope and telescope extend the range of eyes and ears far beyond their natural limits, computers augment memory and calculating skills. But the book is a tool that expands the imagination. It enables readers to soar across oceans, bridge centuries, pace the surface of undiscovered world. And penetrate that most unknowable of zones, the ‘other’. Never mind Klingons and Vulcans. Until we find them, space-aliens remain an abstraction. The true alien is the other person. The person who is not us.

How can we ever know what that other person feels, what they think? We can’t. We assume their motivations equate to ours. That their thoughts are similar to us. That they feel guilt, fear, love, remorse, in pretty much the same way we do. But we don’t know for sure. We can never know for sure. The only way we can assume comparisons, is through what they make. The words they write, the visual images they create, the music they weave. Those are things that evoke empathic reactions. Yes, this approximates. Or no, I can’t connect. A range of ideas that say we are not alone, we are not as unique as we sometimes like to imagine. Pretty much everything we think, feel, do, or imagine has already been thought, felt, done, or imagined by someone else. Until we evolve telepathy, this is as close as it’s likely to get.

Books multiply life. When it gets to specifics, fictional genital organs actually feel nothing. Neither do fictional hands, or breasts, or lips. They are only textual receptors, accepting and transmitting impulses. It is the brain that feels, it is the interpretation of those impulses that makes pain, or pleasure, agony or orgasm. Porn can become an erogenous zone in itself. Hard-core makes you hard. But then so does soft-core. Reading it gives you an erection, or it can make you moist. In other words, it has a direct effect on your physical condition. It brings about a quantifiable change in your physical state. Other forms of literature can have a variety of intellectual or emotional ways of touching you. But they cannot alter your physical state. Only porn can make hard what was initially quiescent, and moist what was formerly dry.

But fact is, suggestion is enough. Imagination does the rest. A dirty mind is a perpetual feast. If ‘Love is the Drug’, porn is its equivalent of sniffing glue, cheap, dirty, and highly addictive. Explicit is good. But in truth the male mind-set is wired in such ways that an image can be insinuated almost without trying. Think SF writer Lester del Rey’s 1938 “Helen O’Loy” (included in his collection ‘And Some Were Human’, 1948), a short story in which an alloy android named for a rhyming elision of ‘Helen of Troy’ with ‘Helen of alloy’ is programmed with desire and the capability to love. Decades before Data in ‘Star Trek: The Next Generation’, del Rey was conjuring with the contradictions of artificial intelligence, the existential enigma of what is authentic, and what is inauthentic. ‘To me, I’m a real woman’ pleads android Helen, ‘and you know how perfectly I’m made to imitate a real woman… in all ways. I couldn’t give him sons, but in every other way… I’d try so hard. I know I’d make him a good wife.’ We know precisely what’s on offer. The story is a harmless little fantasy, yet she’s inflaming the imagination with images or glitch-free robot sex, deleting messy human uncertainties and inadequacies.

Because real women are still unpredictable, unknowable creatures. Understanding quantum physics and Big Bang string-theory is a push-over when compared to understanding the female of the species. Then I meet Clementine. In the cartoon I’m recalling now, the two lovers are naked from the waist down. The boyfriend stands at the bedroom door while she kneels behind the bed, her bare bottom pertly rounded. Her parents have just come home, and caught them at it. Father lectures ‘in my day, young fellow, we kept our trousers ON when we kissed a girl goodnight.’ This is ‘Clementine’ from 1959 – the creation of Jean Bellus with anglicised captions added by Douglas McKie and William H Cole for a series of Panther paperback cartoon collections, ‘Clementine Cherie’, ‘Clementine And Her Men’ etc.

‘She’s charmingly naughty, deliciously saucy, and absolutely irresistible’ runs the blurb. I was twelve, and already seduced. French girls, of course, are different. And she is a cartoon fantasy who keeps turning up naked, guileless, guilt-free, and innocent in all manner of strange social settings, ordinary – but also sensuously erotic in ways that you always hope real girls will be. My life from this point on will be a quest for Clementine facsimiles. In a sense, I guess I’m still looking.

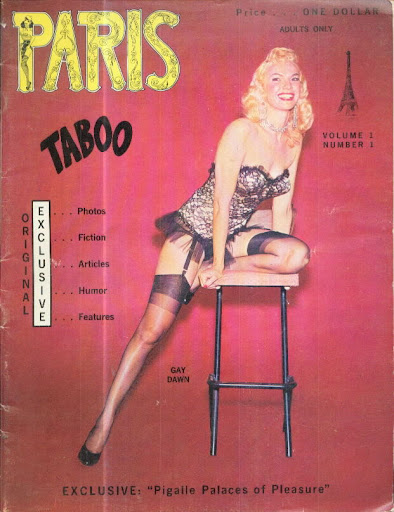

While – in the meantime, soft-porn magazine Leggy Lovelies are always reliable, unlike real life girls. They don’t laugh at you. They don’t back away from you. They don’t reject or humiliate you. And suddenly, they’re always there. Unfrocked gusset-bustin’ girls suffering from uncontrollable outbursts of erotic underwear. Coy cuties of cheesecake with that elusive female geography always nude. Spread-legged and smiling. Oodles of the slim and the beautiful, the lissom and the slightly less than modest. Read by puny adolescents with acne, hair-trigger erections, and over-developed right arms, these girls – more Barbara Windsor than Brigitte Bardot, rule in the now-forgotten glamorama of yore, in ‘Adam’ or ‘Jem’, in ‘Spick’ or ‘Razzle’. Naked-but-airbrushed temptresses in bouffant hair… and little else. Here is my mag-stash of saucy smut, nude Babes on Parade, pin-up Ladeez in baby-doll nighties, and Nudeniks. A private labyrinth of desire where off-the-peg clichés never cease to titillate, ‘a wiggle in her walk, a giggle in her talk.’ Mammaries, they say, are made of this, and it is here, as a 1960s pubescent peruser of prurience, that a Kleenex first becomes an essential aid to reading.

To female sensibilities, this male obsession with ogling voyeurism is silly, so they turn those fantasies into gleefully ribald Benny Hill comedy. Those wheezing red-faced perves glimpsing hints of up-the-skirt anatomy and teetering high heels, their now-you-see-it now-you-don’ts seem so foolish and ungainly. This earthier female realism fails to identify the idealisation in the intense fetishisation of their everyday body-parts. The mystique that lies in their unattainable alienness. Of course – Porn, almost by definition, is about as politically correct as the Third Reich. But erectile tissue knows nothing of what is or what is not politically correct.

BY ANDREW DARLINGTON