The prevailing genius of American comix (as opposed to “comics”) during the twentieth century has long since been acknowledged to be Robert Crumb (sometimes R. Crumb), whose exquisite and wide-ranging oeuvre is known the world over for its boisterous use of language, its festering misanthropy, its juvenile instinct for humor, its confident crosshatching, its daring deployment of lettering, its affinity for kink, and much else besides. Of all the cartoonists who emerged after the syndication/dimestore period of the first half of the twentieth century, it’s safe to say that none of them has so consistently produced work that is as widely familiar and as preternaturally compelling.

Like many others, Crumb, who entered the world in 1943, had an apprenticeship period in his late teens and early twenties, and in Crumb’s case he kept body and soul together primarily for the American Greetings company in Cleveland, Ohio, even while he was traveling widely—to Europe, to New York, to Chicago, to San Francisco—even while he was infiltrating and in some measure helping create the underground comics tradition mostly associated with the West Coast, even while he was famously having his mind expanded with some high-octane LSD-25 (as it was called at the time) and even while he creating ground-breaking narratives of questionable taste involving sex and race. Years after e.g. contributing to Zap Comics and inventing many of his characters such as Mr. Natural and Flakey Foont, he would still draw a paycheck from American Greetings into the 1970s.

Unsurprisingly, a temperament as touchy as Crumb’s was seldom discerned to be content working for a corporation dedicated to transmitting saccharine and ingratiating content to the great middle class, but the experience did shape Crumb’s art in significant ways—as the artist himself grumpily acknowledged. His boss there was a man named Tom Wilson, who created Ziggy—which some of Crumb’s work at American Greetings distinctly resembled.

Crumb spent significant time in Cleveland, and while he had and has some affection for the place, he seems to have spent most of his stint there trying to get out. (Of course, it was also where he met Harvey Pekar, with whom he collaborated fruitfully.)

Crumb started working at American Greetings in 1962 at the age of 19. By the autumn of the next year he was assigned to the Hi-Brow cards division. Around the same time he took a sort of sabbatical and visited Europe for several months with his wife, Dana. In June 1965 he had his first truly formative experience with LSD, which messed up his head quite badly for several months (an event for which his fans are eternally grateful, of course). In August of the same year he went to New York to work on a magazine called Help!, which folded as soon as he got there. He worked for the Topps trading card company for a couple of months and then returned to Cleveland.

From November 1965 to April 1966 he was in Chicago before once again returning to Cleveland. In May 1967 Crumb headed for San Francisco, where he made inroads in the underground comix scene and established his reputation once and for all. During the same year, the Lakeview Center for the Arts and Sciences in Cleveland put on a show dedicated to his works. While he was in San Francisco he contributed to American Greetings by mail. It seems that the San Francisco trip did, finally, put an end to Crumb’s status as a Cleveland resident, although he notably returned to the city for a while in 1971, during which time he met up with Pekar again.

Here’s a selection of Crumb’s remarks on his time on Ohio’s northeastern shore:

Of all the big cities I’ve been in, Cleveland’s about the deadest or something. But that’s only in certain ways. In other ways I really like Cleveland, ya know? It’s like the lowest common denominator or something. Like you can get right down to basics here or something. Like in Chicago, Milwaukee, or Detroit or Denver or a lot of other towns, I can get a lot of attention from people who appreciate artists. Like I get a lot of ego build-up that way, but Cleveland’s a big dumb town.

I was here off and on for three or four years. I came here when I was nineteen after I left home to look for a job and to live with my friend Marty Pahls, and I was here like two weeks and got a job with American Greetings doing color separations. So I worked in the color separations department for about a year and then I was promoted to the Hi Brow department for about a year and then I got married and went to Europe and came back and worked American greetings again for about two months and then I decided to fuck Cleveland and went to New York to try to make it big in New York.

I was there for nine months and I said fuck New York and came back to Cleveland. Worked in Cleveland for about another eight months or something and then I went to San Francisco.

The boss kept telling me my drawing was too grotesque. He got me to draw this cute stuff, which influenced by technique, and even now my work has this cuteness about it.

I’m pretty sure that that mention of “the boss” there is a reference to Tom Wilson. All of these quotations come from D.K. Holm’s invaluable volume R. Crumb: Conversations, published by the University Press of Mississippi in 2004; the book also has an extremely useful timeline of Crumb’s career.

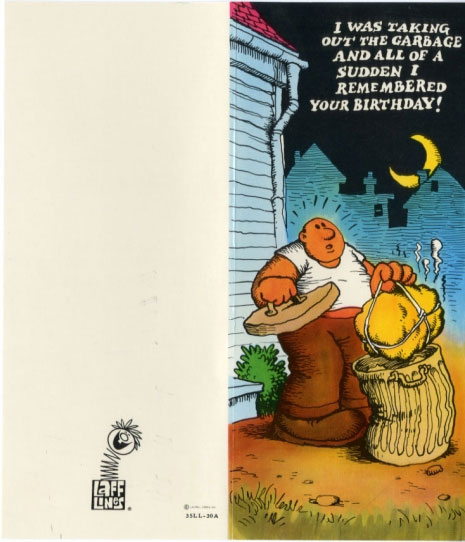

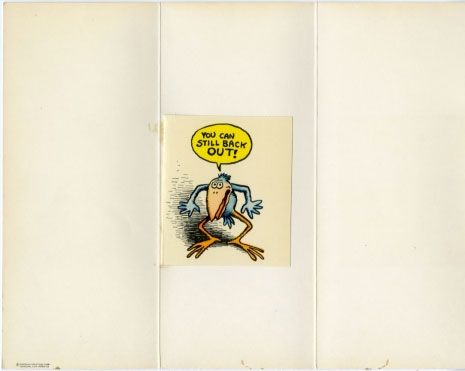

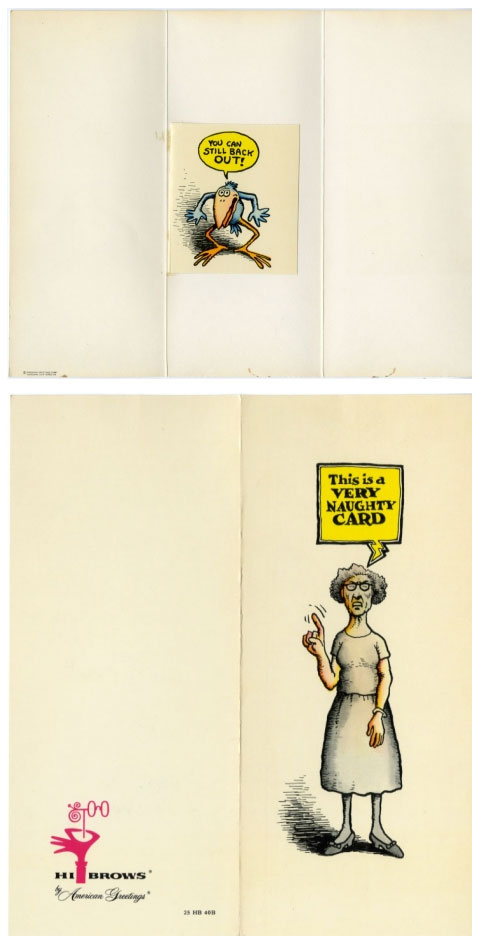

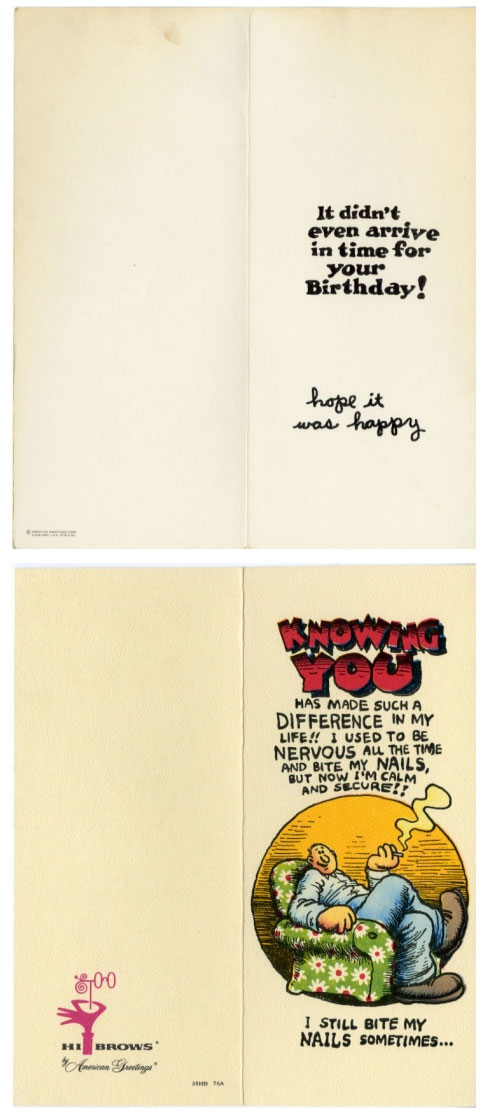

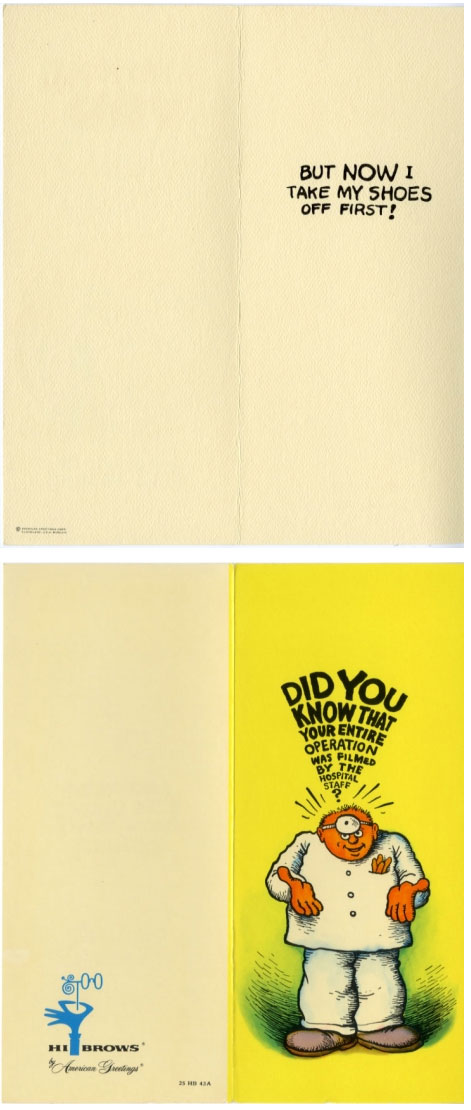

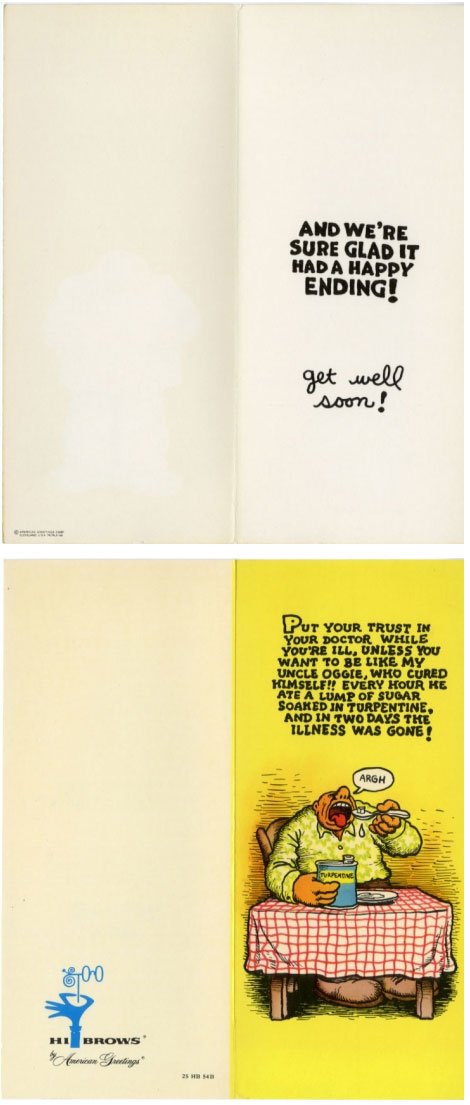

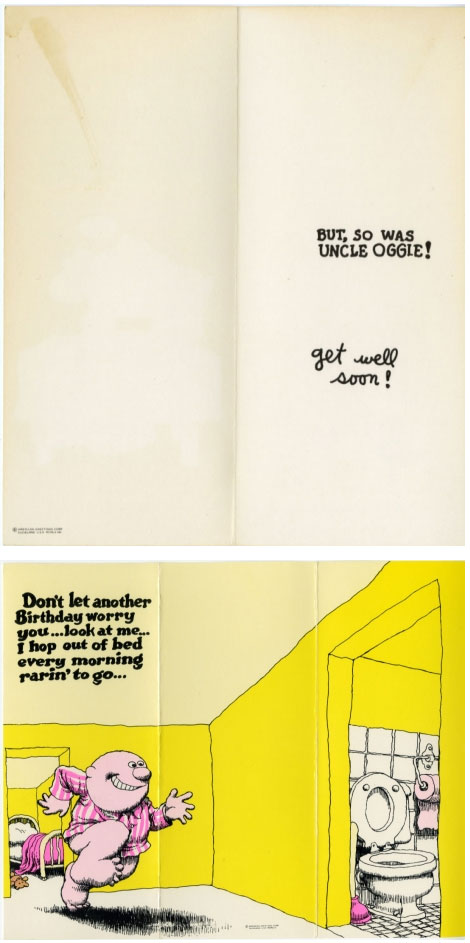

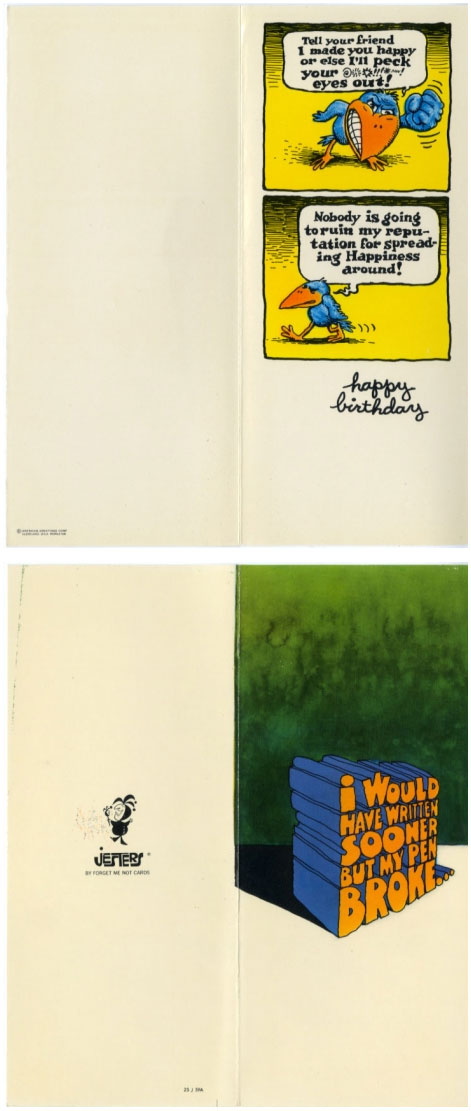

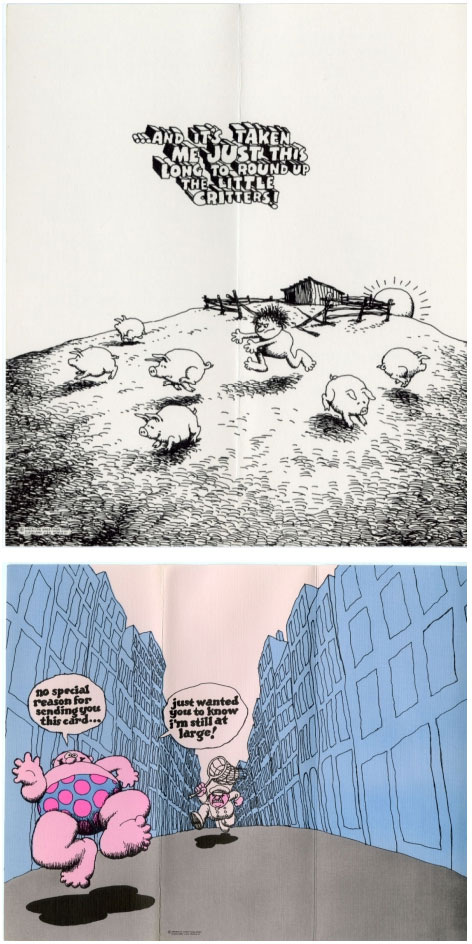

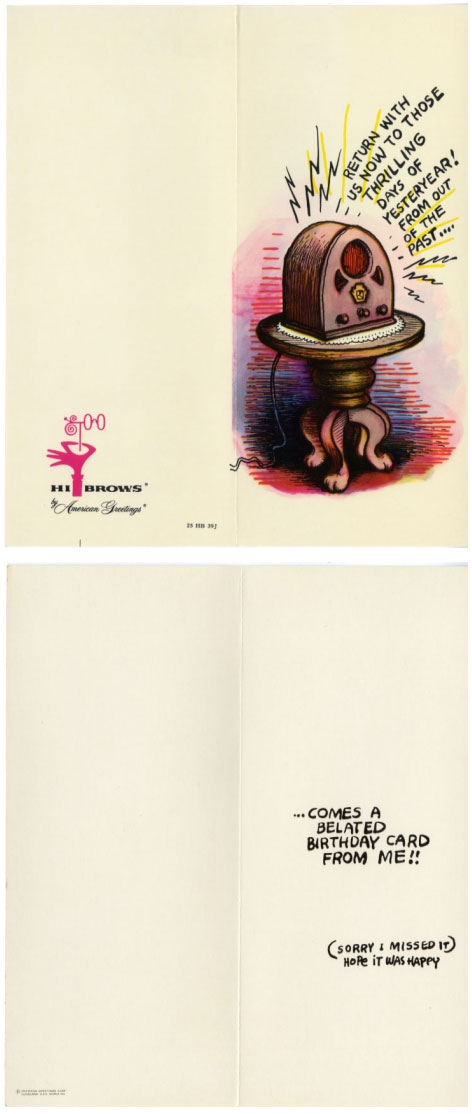

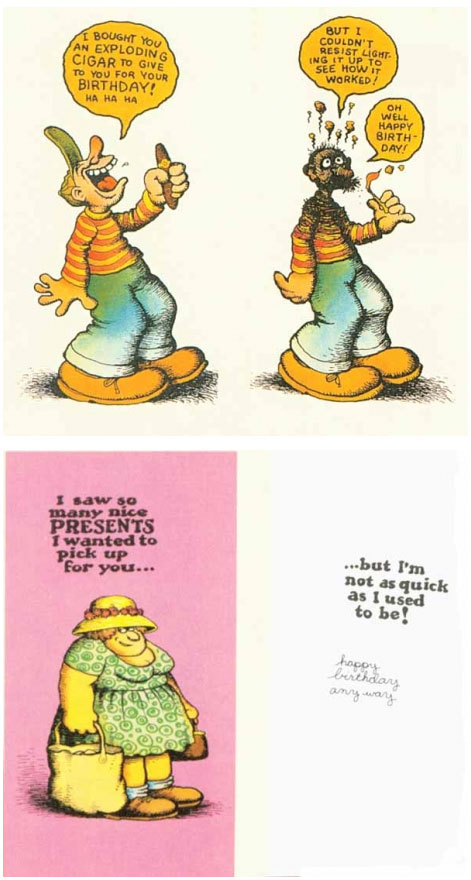

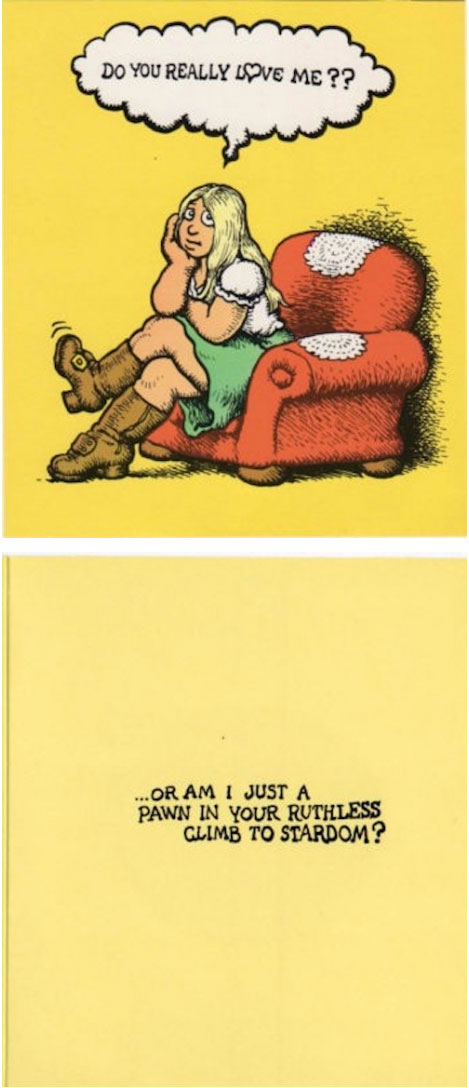

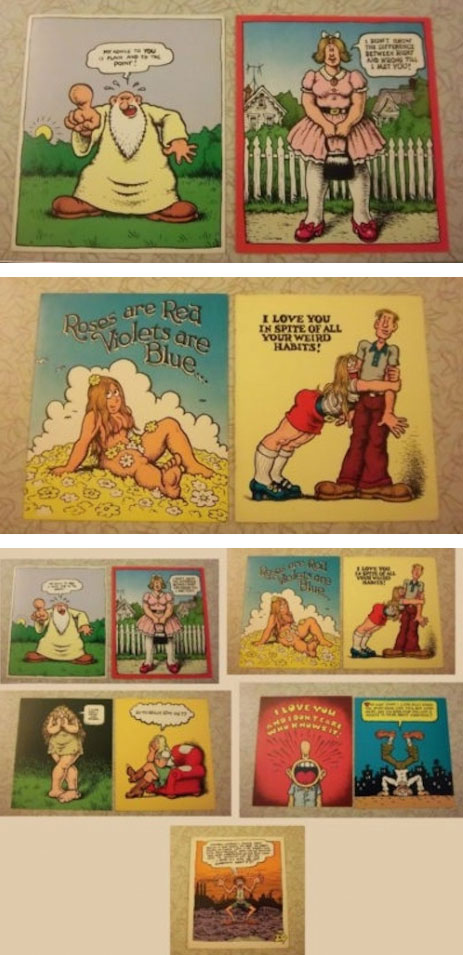

As you can see below, most of the Crumb art that is available to present-day fans was executed as part of that Hi Brow department. Those cards have a strikingly vertical format and feature the typical setup [open] punchline structure long associated with greeting cards. Not all of the cards particularly seem like the work of Crumb, but several do, and most of them do feature the kind of off-color or gross-out humor that Crumb is famous for enjoying.

The cards featured below aren’t dated, but its seems logical that the small number of cards that have a definite Ziggy feel to them—such as the yellow one with the phrase “rarin’ to go” and the blue one with the phrase “no special reason”—stem from earlier in Crumb’s tenure at American Greetings, while the ones that feature artwork that seem snatched directly from one of his comix panels—such as the one that starts “Knowing You” and the one with the radio—come from a period after Crumb had made inroads in establishing his distinctive style.

At some point he was involved with a line of cards called Jesters, which were similarly vertical in appearance. After he was more established, in the early 1970s he did a series of cards in a line called Zonk!, and those cards in particular are very in line with the work he was producing elsewhere—they almost seem explicit about this, as if the consumer were consciously buying some groovy cards by that R. Crumb guy. Remarkably, one of them actually features Mr. Natural!

Martin Schneider

Origanally from https://dangerousminds.net/