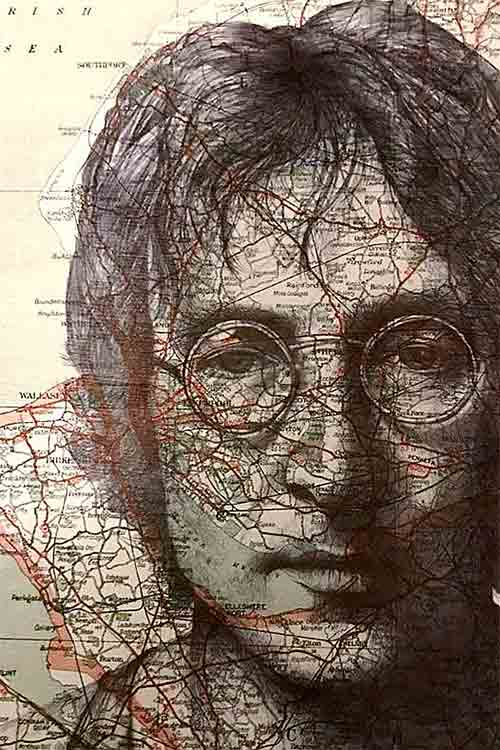

(Artwork: Pip Pickles)

Some thoughts about John in these Covid times…from Alan Dearling

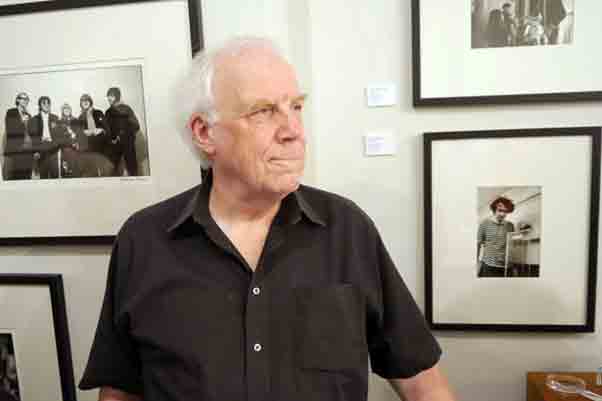

Many of my mates and co-workers from various times were centrally involved with the development and blossoming of the UK’s underground music, media and arts scenes. I was on the periphery (I was just getting ready for my university mis-education!) and became much more involved from about 1968 onwards. Among the early ‘movers and shakers’ were my two friends, Dave Robins and Graham Keen – both sometime editors of ‘international times’. Graham was significant photographer of that time – the mid to late ‘60s as flower-power and hippy ideologies overtook his more Bohemian world of jazz. But he was there at the opening of the Indica Gallery which Paul McCartney rather than John Lennon cofounded. You can see Graham’s pic of Barry Miles, John Dunbar, Marianne Faithful, Peter Asher and Paul, to the left of Terence Pepper who curated Graham Keen’s ‘1966 and All That’ photographic exhibition.

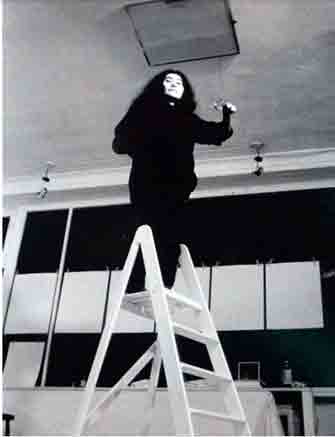

But to put the 1966 Indica Gallery and Yoko Ono’s show there in context, here’s

Paul (in the Beatles’ ‘Anthology’):

“People were starting to lose their pure pop mentality and mingle with artists. We knew a few actors, a few painters, we’d go to galleries because we were living in London now. A kind of cross-fertilisation was starting to happen.

While the others had got married and moved out to suburbia, I had stayed in London and got into the arts scene through friends like Robert Fraser and Barry Miles and papers like the ‘international times’. We opened the Indica Gallery with John Dunbar, Peter Asher and people like that. I heard about people like John Cage, and that he’d just performed a piece called 4’ 33” (which is completely silent) during which if someone in the audience coughed, he’d say, ‘See?’ Or someone would boo and he’d say, ‘See? It’s not silence – it’s music’.

I was intrigued by all of that. So those things started to be part of my life. I was listening to Stockhausen, one piece was all little plink-plonks and interesting ideas. Perhaps our audience wouldn’t mind a bit of change, we thought, and anyway, tough if they do! We only ever followed our own noses – most of the time anyway. ‘Tomorrow Never Knows’ was one example of developing an idea.

I always contend that I had quite a big period of this before John really got into it, because he was married to Cynthia at that time. It was only later when he went out with Yoko that he got back into London and visited all the galleries.”

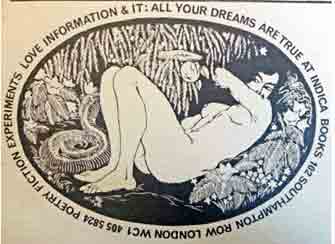

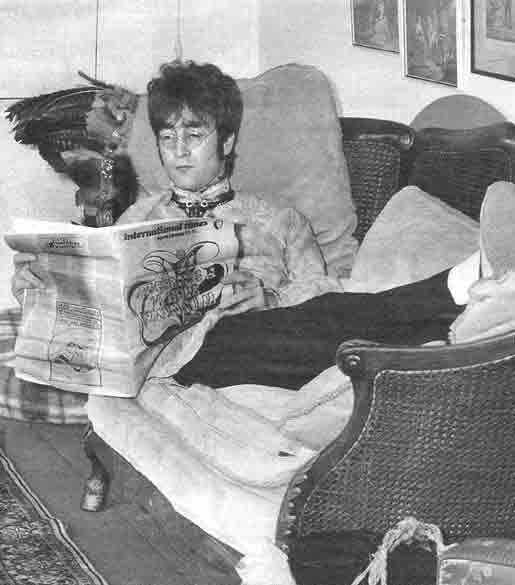

But this was the time and place, the Indica Gallery, when John first saw Yoko’s work (photo: Graham Keen), met her, and became gradually in thrall. The late 1960s was like that. A time of heady optimism, social upheaval and ‘dreams’. And the underground press in the UK, first with ‘international times’ was launched on 15 October 1966 at The Roundhouse at an ‘All Night Rave’ featuring Soft Machine and Pink Floyd. Here’s what is says in ‘Wikipedia’:

“The event promised a ‘Pop/Op/Costume/Masque/Fantasy-Loon/Blowout/Drag Ball’ featuring steel bands, strips, trips, happenings, movies… The launch was described by Daevid Allen of Soft Machine as ‘one of the two most revolutionary events in the history of English alternative music and thinking.’ The IT event was important because it marked the first recognition of a rapidly spreading socio-cultural revolution that had its parallel in the States.”

Barry Miles takes up the story:

“It started at 11 p.m., the Pink Floyd and the Soft Machine played and everyone was given a sugarcube as they entered. People were still arriving at 3 a.m.”

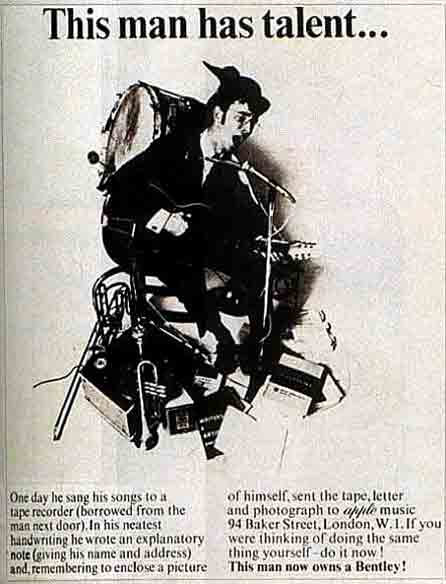

John quickly became a fan of the underground media. In fact, throughout his sadly shortened life he fought for the underdog, the oppressed, and against war, capitalism, out-dated drugs’ laws, censorship, popular and less popular causes ranging from support for the Black Panthers and the IRA, to John Sinclair, jailed for possession of two marijuana cigarettes. But at times it was messy, John was wonderfully naïve. Despite the conflicting pressures of co-running the idealistic, but doomed business empire, known as Apple Corp, he wanted to be part of the ‘revolution’. He was featured in ‘international times’ in a rather wonderful advertisement attempting to recruit new talent to the label. A very mixed message regarding fame/money/talent!

‘Miles’ reminds us: “With very few exceptions, underground papers were non-commercial; written by and existing only to serve their community. The staff often did not get paid, no one made any profits. The people who made the papers created communities and a culture, and thus shaped the identity of each of the papers. A lot of IT’s readers smoked marijuana, and some of them took LSD. As the British counter-culture grew and developed, IT became the chief outlet for news of the alternative lifestyle with articles on ley lines, numerology, Arthurian legends, Eastern mysticism, Tim Leary and his cohorts, macrobiotics, vegetarianism, ecology, communal living and of course drugs.”

John Lennon was frequently featured in both ‘international times’ and Richard Neville’s ‘Oz’. And the Beatles helped support the underground media by placing adverts for their albums in the papers.

John Peel’s career was virtually created by ‘Beatlemania’ over in the USA. By becoming an instant Liverpool and Beatles’ expert, he started work in the US, post- a short period in the army. Peel’s ‘Perfumed Garden’ column in ‘it’ and programme of the same name on Radio London in 1967 were much loved. Along with his colleague, Kenny Everett, they absolutely championed the new psychedelic Beatles. Miles suggests that, “…Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band’s first play reduced Peel to tears, and became an essential part of the Perfumed Garden playlist; its atmosphere, a mixture of psychedelic strangeness and images drawn from everyday British life, was reflected in Peel’s presentation style, alternately dreamy and down-to-earth. As a Liverpudlian, he sought to distance himself from the fashionable cliques of ‘Swinging London’, hoping that his programme, its ethos expressed in the Beatles’ song, ‘All You Need Is Love’, would appeal to a wider audience.”

Peel wrote regularly for ‘it’ and in 1968 according to the Beatles’ Fandom page on the web they published a somewhat mysterious ‘Memo to J.L.’ – but I cannot locate it – despite a fairly serious search on the internet! John Lennon certainly was a guest on Peel’s ‘Night Ride’ on 11 December 1968. Less known, perhaps, is the fact that John Lennon also provided financial backing for a re-launch of ‘international times’ in 1974.

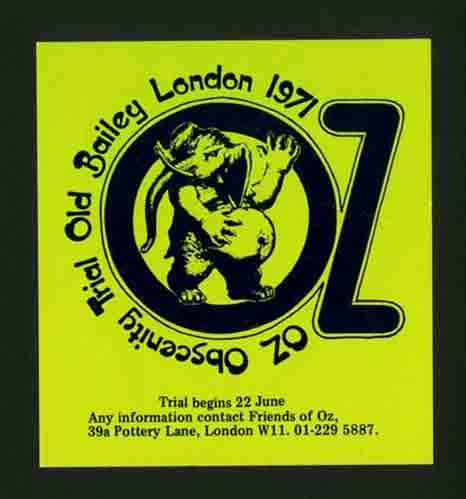

Both ‘international times’ and ‘Oz’ were regularly harassed and raided by the police. In fact, Oz magazine was at the centre of the longest obscenity trial in British history in 1971, after it was raided by the obscene publications division of the Metropolitan Police.

Felix Dennis, Jim Anderson and Richard Neville were charged with conspiring to corrupt the morals of the young after the magazine printed an issue curated by a group of school children, which included a rather naughty and sexually explicit parody of the cartoon, Rupert Bear. The Friends of Oz campaign group was established and The Elastic Oz Band was formed. ‘God Save Us’ featured John Lennon and Yoko Ono as part of their fund-raising protest over the trial.

Again quoting Barry Miles, he provides a link between those heady times in the late ‘60s and early ‘70s with 2020:

“But I think that there is a lot of brave journalism out there, mostly on the net, including Wikileaks (despite what has been happening recently with Assange). The fact that the police feel it is necessary to have undercover agents in the students’ movement, in the animal rights movement, and presumably in any left wing radical groups, shows that there is still a spirit of dissent in Britain (I don’t follow the USA closely enough any more to say what’s happening there). Not everyone in Britain has become a mindless consumer and I think there is only so far that you can push people, even if they are being brainwashed by the right-wing press. Maybe we will see the return of the legendary ‘London Mob’ and people will carry Gove and Hunt and Johnson’s heads through the streets on pikes. After Trump getting in and Britain voting to leave Europe anything can happen, even the most unlikely. I am pleased to see that IT is, in fact, still publishing. There was even a paper edition a few months ago, so 50 years on the old underground is still putting out roots.”

The UK’s underground press was a major force for counter-cultural change. At its height International Times was printing 44,000 copies and each copy was often read by four or five people. Oz, in the ‘60s, was selling about 30,000 and a great deal more during the obscenity trial of 1971. John Lennon and Paul McCartney played a significant role.

Another quirky episode in John and Yoko’s life maybe has a tenuous link with ‘international times’ and the underground counter-cultural scene. Sid Rawle, frequently hung around the ‘it’, Release and BIT alternative information and publishing offices, probably Oz too (the ‘counter culture’ was like a small ‘family’, friends and fall-outs included!). I think it is probably where John Lennon and Sid Rawle first bumped into each other. According to Tracy McVeigh in the ‘Observer’ newspaper (22/9/2012):

“John Lennon bought Dorinish – twin green mounds linked by a natural causeway, lying just 15 minutes from the west coast of Ireland – in 1967 and got planning permission, although he never got as far as building. He shipped in a multicoloured caravan and took both his wives there.

‘He was besotted with the place by all accounts,’ said Andrew Crowley (a local estate agent). But at the height of Beatlemania Lennon wasn’t ready to settle into his island retirement and so he offered it out, rent-free, to Sid Rawle. Rawle, the man the newspapers liked to call the ‘King of the Hippies’, was the founder of the Digger Action Movement. He was a New Ager, interested in self-sufficiency, when he was summoned to the Beatle headquarters in 1970 and offered the use of Dorinish by Lennon to try to build his utopia. Rawle had great plans for livestock and lobster pots and vegetables. But as 30 hippies with their Carnaby Street costumes and teepees arrived, local residents were horrified, remembers Sam Kelly, 63, a retired farmer from nearby Westport. ”

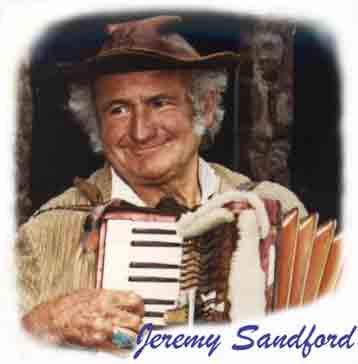

In my book, ‘Travelling Daze’ I included a long section about Sid, who, for better or worse, played a significant role in new Traveller history in the UK. I put a lot of it together with considerable help from the Jeremy Sandford (author of ‘Cathy Come Home’ and many other fabulous books). Jeremy and myself were involved with Sid, getting him to tell his life story orally. He wasn’t very trustworthy – a born ‘story-teller’. But Lennon was impressed with Rawle’s ‘revolutionary rhetoric’ and gave his group ‘custodianship’ of Dorinish for the ‘common good’. Here are a few extracts:

Sid Rawle: “We decided we would hold a six week summer camp on the island. Then we would see what came out of that and decide whether we wanted to extend our stay. It was heaven and it was hell. We lived in tents because there were no stone buildings on the island at all.”

The ‘Connaught Telegraph’ reported in March 1971: “After a year of seething anger, Westport has finally declared war on the ‘Republic of Dorinish’ – but the commune finally closed down of its own volition the year after, when a fire destroyed the main tent used to store supplies.”

You can see why John Lennon admired the visionary hippy, Sid Rawle, who told Jeremy Sandford:

“There’s talk of community in war time. We can be ordered to go and fight and die for Queen and Country. In peace time, is it too much to ask for just a few square yards of our green and pleasant land on which to rear our children on? That’s all we want, myself and the squatters and Travellers and hippy movements I’ve been involved with… And if we achieve that, what else? ‘What else’ is what I call the ‘Vision of Albion’.

We have to reclaim some of the ancient wisdom. The wisdom of ancient Albion.”

Video of Dorinish by Shay Fennelly: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FrK8ejzWD9Y

Sam Kelly in ‘The Observer’ article adds:

“ ‘You saw them waiting to go out, and some of them were back pretty quick, too. It didn’t suit too many of the rich, pampered kids. In town we just all thought the man must be making a lot of money out of it all, but then thought, fair game to him when he made it through that first winter. We thought the place would be flooded with drugs, but not a sign of them – flooded with letters is all. People writing to him and sending money from all over the place.’

‘You never saw them in town. Only Rawle himself came in for anything they needed – the welfare cheques, of course. He didn’t even have a boat: he’d hoist a white bedsheet up when he wanted Tommy, one of the local guys with a boat, to come and get him,’ said Kelly, who said he doesn’t think that the hippy era left a lasting legacy.

‘We’re maybe a bit more bohemian than most parts of Ireland, but we had pirates living here long before the hippies. Sid Rawle was more a dreamer than a drug crazy.’ “

And that is even more of a truth for John Lennon too!

John from ‘Anthology’:

“I’ve grown up. I don’t believe in father figures anymore, like God or Kennedy or Hitler. I’m no longer searching for a guru. I’m no longer searching for anything. There is no search. There’s no way to go. There’s nothing. This is it. We’ll probably carry on writing music forever.”

Would that it were true.

Alan Dearling with the statue of John Lennon in Vilnius, Lithuania.