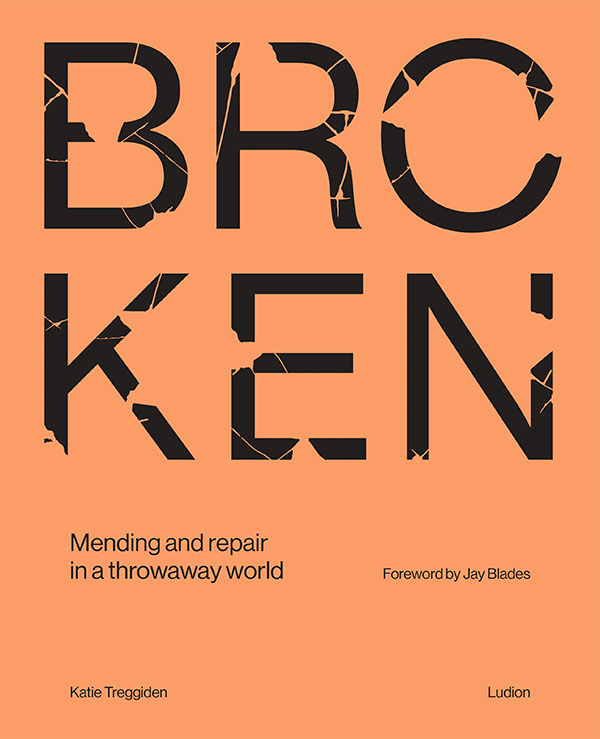

Broken, Katie Treggiden (Ludion)

I confess that this book’s subtitle ‘Mending and repair in a throwaway world’ but mostly the fact that the Foreword is written by Jay Blades put me off reading this book for a while. Both are in many ways irrelevant to what this book is actually about; it certainly has very little to do with the tearful nostalgia peddled by TV’s Repair Shop (which Blades presents) as they return mended items to their grateful owners. It is also not about ‘making do’ or ‘patching things up’ but much more radical and interesting topics such as ‘Repair as storytelling’, ‘Repair as activism’, ‘Repair as healing’ and ‘Regeneration as repair’.

These are the titles of the book’s individual sections, the first of which is to do with the seemingly more ordinary ‘Restoration of function’, which talks to makers who have skills such as chair caning, and to the inventor of Sugru – a plastic I have never heard of but looks absolutely fantastic. It is a ‘mouldable glue’, made in a number of vibrant colours, which has the ability to be wrapped around or between all manner of previously difficult-to-repair items such as cables, zip tags and, if you don’t mind a crazy paving look, ceramics. Some of those featured here talk about resisting a throwaway society but also more importantly of the fact that ‘Fixing objects is a way of taking ownership’. Disappointingly, Vincent Dassi who I have just quoted, along with Jude Dennis & Hannah Stanton, who ‘use furniture as a medium for the exploration of ideas’, create objects that most people, myself included, will probably not want in their home. That’s actually unfair to Dennis & Stanton, as they use their chairs as sculptural props in performances designed to provoke their audiences to ‘think differently about their furniture, what’s in it, where it comes from, and who has made it.’

‘Repair as storytelling’ is about the history that objects we own sometimes contain, and that we perhaps need more than we think as humans living in a throwaway society where built-in obsolescence is the norm. Whilst we find it hard to manage our clutter and possessions (let alone digital information) we all too often end up rootless and unable to position ourselves within familial, communal or social histories and geographies. Keiko Matsui notes that ‘People will not repair a broken object if it is not personal, valuable or historical… it must have a story, a connection to the heart, in some way.’ Re-animating, discovering or perhaps even inventing such stories seems to be what the artists in this section are doing. Celia Pym highlights the darns and repairs she makes in bright colours to construct fashion items which map ‘where holes happen’, but also makes sculptures or reliefs from stitching wool into paper bags, emphasising the crumpled textures and darning interventions.

Bouke de Vries reassembles broken ceramics in a deconstructed manner, sometimes highlighting the repaired cracks with gold leaf, at other times placing the pieces in a glass version of the original pot. Matsui at times does something similar, drawing on the art of kingtsugi, which embraces damage and repair, but she is also exploring yobtisugi, where missing fragments are replaced with pieces from other ceramics. In her case this often involves using ‘old shards if blue and white Japanese porcelain, in a way that integrates [her] identity with the cultural connection to my new home in Australia.’

Raewyn Harrison explores similar ideas of cultural connection by curating and assembling found objects, often from mudlarking expeditions by the Thames, into handmade porcelain boxes or thrown pots. Hans Tan initiated a design project in Singapore to challenge design students to repair objects for an exhibition he curated, R for Repair. The students also had to produce a little ‘repair kit’ which would enable others to do something similar. This wasn’t simply about ‘mending’ but totally rethinking and recontextualising the object. So a watch became a clock by being set in a wooden block; a tote bag was turned inside out, with elastic rope netting added to the (now) outside as extra storage; a precious cup with its handle broken off was smoothed down to make a usable drinking vessel for its owner, whilst the handle was given a small wooden box to rest in.

In the next section some makers appear to work in similar ways but frame their practice as political resistance, not only to capitalism’s demands for endless production and purchasing but also the way it ignores poverty, environmental issues, and our broken community and society. It is craft as a form of protest. Sometimes this is in-your-face sloganeering, for instance Bridget Harvey’s giant jumper with the slogan MEND MORE BUY LESS on, carried on the Global Protest March back in 2015, other times it is a more subtle highlighting of the beauty of wear and tear, the inbuilt stories in what we wear. Aya Haidar produces witty installations of used clothing hung on washing lines, with each item’s particular history annotated in stitch: ‘Produced Milk’ declaims a slip, ‘scrubbed poo off pants’ announces a pair of pants, ‘Painted fence’ states an old rag; whilst in other works she highlights stains and marks and tears by stitching colours around them. Other works here may be political acts but once again, you’d have to like them a lot to want Paulo Goldstein’s anarchically DIY repaired furniture in your house or the naively painted, smashed and awkwardly reassembled pots which Claudia Clare sees as a metaphorical representation of sexualised violence against women.

Perhaps more subtle and interesting is the work in the next section, which considers ‘Repair as healing’, referring to personal healing, not the objects concerned. Ekta Kaul’s embroidered textile work explores lost connections, with an early piece mapping out her grandmother’s Indian neighbourhood as a way of exploring her cultural and family past. Later pieces such as ‘Portrait of Place’ were co-created with community groups who learnt traditional Indian stitching techniques in addition to being able to produce a map of their West London, where the workshops took place. (It also happens to be my West London!) I was surprised and delighted to see artist Lucy Willow’s work showcased here, particularly because the work discussed is from an exhibition I saw in 2022. Drawn from the Well was an exploration of grief in response to Willow’s almost 16 year old son dying back in 2006. The work included charcoal drawing and porcelain ceramics, some broken and exhibited as pieces on the floor, others organic yet abstract shapes containing textiles made from her son’s clothes. Deeply personal symbolism, and the artist’s acts of creating by ‘tearing, ripping, stabbing, breaking’ re-present a raw, personal response to loss, and offer a space for others to remember, mourn and think; perhaps to even be healed.

Aono Fumiaki makes sculptural assemblages from what others have discarded, but it is perhaps his reinvention, which he calls ‘restoration’, of items from the great East Japan earthquake and tsunami that is the most striking. Here, original damaged items are seamlessly combined with other items as sculpture or objects: a TV remote is cradled in shaped driftwood, a section of a wrecked boat merges with two occasional tables and rests on chests of drawers. They are strange and alluring, unsettling even, in stark contrast to the more traditional (but beautiful) tables and chairs made by Marie Cudennec Carlisle & Daniel Barco which follow. These craftspeople share woodworking skills through an academy teaching schoolchildren and young offenders, offer free workshops to members of the public on low income, and run a joinery where they make and sell bespoke furniture from donated and rescued wood. They are also active in their community running The People’s Kitchen, which uses surplus food to make restaurant quality meals and offers a space for meeting and eating. They somehow bridge the extreme gap between poverty and affluence the Borough of Kensington and Chelsea offers. Bachor and Linda Brothwell are also hands-on artists in different communities. The former fills in potholes and often tops them with mosaic images, whilst the latter uses skills to intervene, decorate and repair in public spaces: wood inlays in benches, missing letters in old signs replaced using beautiful brass. These are all parts of her Acts of Care project, which she documents as she goes along.

The final section is mostly about sourcing material, being aware of where stuff comes from, and helping to sustain the Earth. It is about makers who choose to build a relationship with not only the materials they use but those who provide it. Artist and designer Fernando Laposse returned to Mexico, where he grew up, and was appalled by the environmental and social changes. He now provides a market for those who grow agave – a resilient self-sufficient plant which helps create good soil that corn can then be grown on – because sisil which is used to make rope is a by-product, and has also invented a veneer material made from the waste products of corn. Sarah Grady and Alice Robinson have established ‘a new network for producing leather in the UK, utilising hides from the farms whose regenerative practices they want to support’. As part of that they ‘maintain traceability through all stages of production’ and give other ‘designers and brands a choice when it comes to the leather they use.’ Sebastian Cox manages his own woodland and uses only coppiced wood in the making of his furniture. He remembers being amazed as a child just how quickly a deforested landscape grows back. Gavin Christman is more of an interventionist: he produces blocks, bricks and posts which offer homes for bees, bats, swifts and sparrows, all of which re made to standard sizes and can be included within otherwise normal construction practices

I don’t like all of the work showcased in this volume, and there are questions to be asked about how fine art or crafts can change the world beyond highlighting or showcasing issues; especially when they remain part of the capitalist marketplace. But many of the projects here which also intervene to mend, repair and change attitudes, communities and skillsets are provocative and fascinating to read about. I also remain drawn towards Willow’s exploration of grief (something our society does not cope with very well), Harrison’s recontextualisations of what the Thames offers up to her and us, along with Haidar’s subtle evocation and highlighting of personal histories embedded in clothing.

As I implied at the start of this review, this book isn’t really what I expected it to be. It’s much wider, more thoughtful, more diverse and much better in its content, contextualisation and considerations. I can’t summarise it better than this quote which prefaces Katie Tregidden’s own Introduction:

… other things can be repaired. Objects, of course.

Traditions can be. Hope can be. Emotions eventually.

But it requires cautious handling, patience and care.

Old hope can age beautifully.

– Otto von Busch

Rupert Loydell