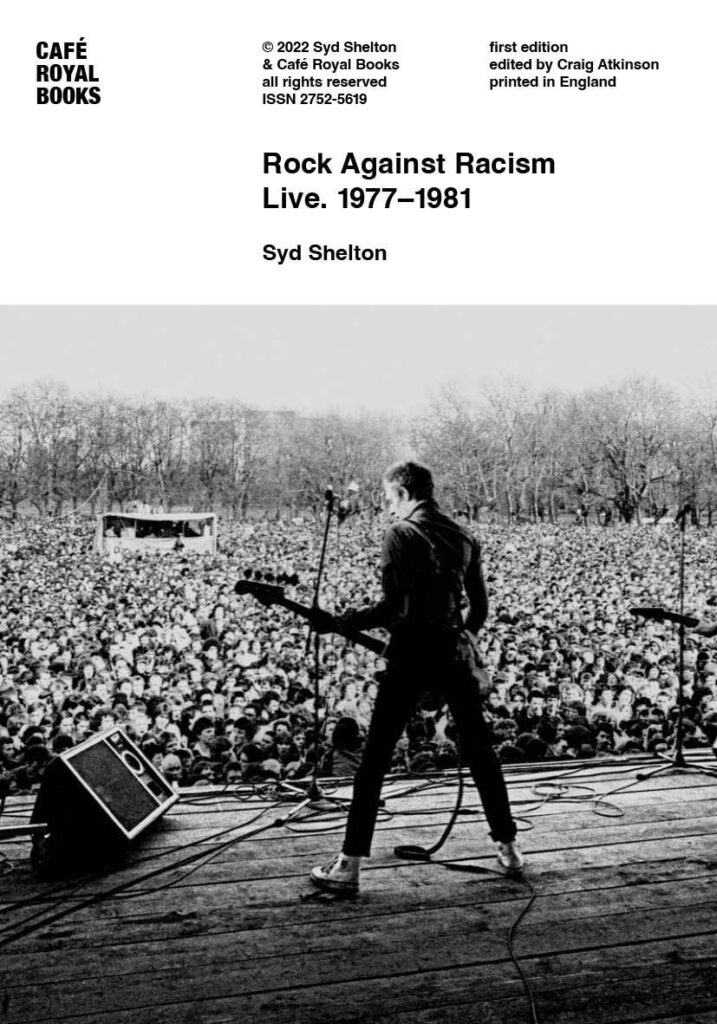

Rock Against Racism Live. 1977-1981, Syd Shelton (32pp, Café Royal Books)

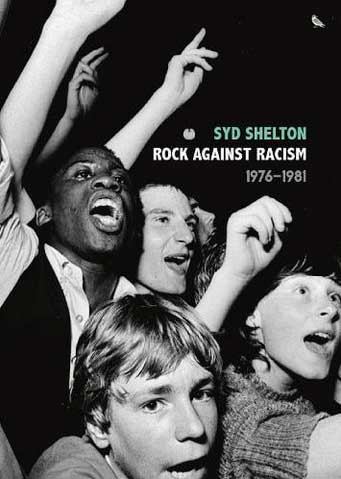

Syd Shelton: Rock Against Racism 1976-1981, eds. Carol Tulloch and Mark Sealy (187pp, Rare Bird Books)

Back in the 1970s, as unemployment rose and wages fell, there was a right wing backlash against immigration. So much so that by the middle of the decade the National Front had become a serious threat in party politics, and racism was openly practiced and an everyday occurrence. Graffiti encouraged ‘blacks’, ‘pakis’ and ‘wogs’ to ‘go back home’, often accompanied by swastikas, whilst the streets in poorer areas of many cities turned into spaces for beatings, fights, abuse and shouting matches. If you want to be kind you can talk about the confusion of nationalism and racism, patriotism and separatism, or about immigration policy and the fear of unchecked immigration, but I don’t want to be kind. This was mob paranoia, mass ignorance and racism, and the National Front were intent on using that, stirring things up and getting into power. They recycled and repeated Enoch Powell’s 1968 ‘Rivers of Blood’ speech [1], and spread the lies and misinformation that we now know as the Great Replacement theory [2]. It was a particularly successful message in working class areas where jobs were disappearing as industry declined.

It wasn’t of course, as clear-cut as this seems. As Mark Sealy says in his ‘Introduction’ to Syd Shelton: Rock Against Racism 1976-1981, it was

one of the most intriguing and contradictory political periods in post World War II

British history. A time when racist skinheads danced to Jamaican ska, punks

embraced reggae and Black kids reached out to punk. Meanwhile disaffected white

Britain turned to rightwing politics […]

For some music fans such as Roger Huddle, writing many years later in Socialist Worker, things came to a head in August 1976, ‘when Eric Clapton made a sickening drunken declaration of support for Enoch Powell (the racist former Tory minister famous for his “rivers of blood” campaign against immigration) at a gig in Birmingham.’

Outraged at not only Clapton’s speech but also the fact that ‘it was all the more disgusting because he had his first hit in 1974 with a cover of reggae star Bob Marley’s “I Shot the Sheriff”‘, Huddle and his friend Red Saunders ‘wrote a letter to the New Musical Express and signed it’. They ‘finished the letter by saying that [they] were launching a movement called Rock Against Racism (RAR), and anyone outraged should write to us and join.’

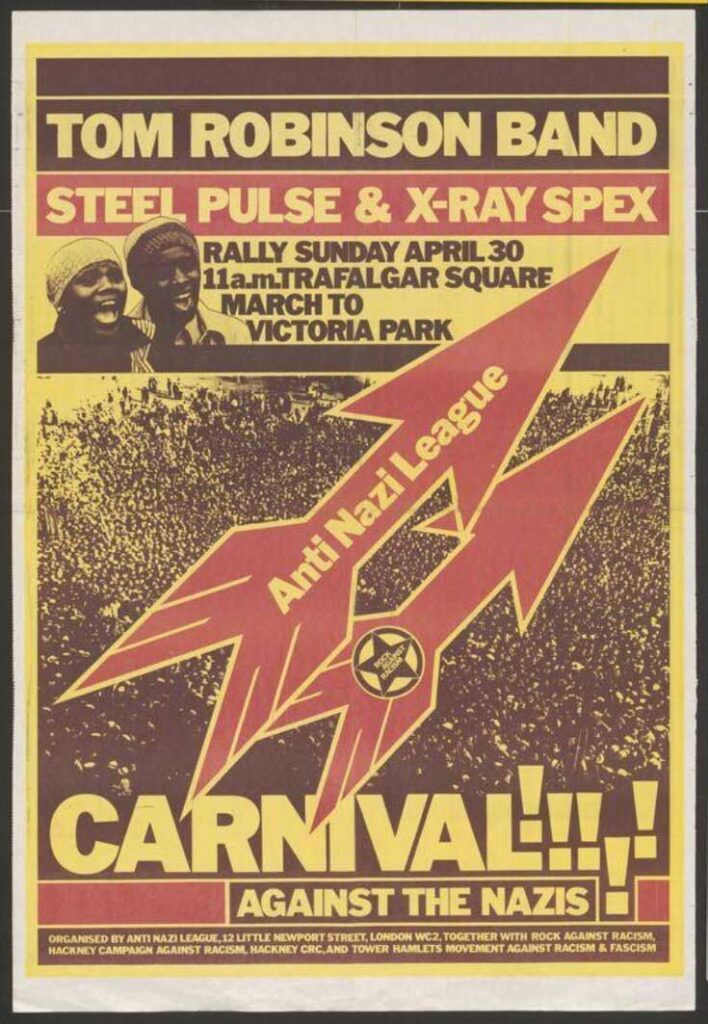

Hundreds wrote, ‘but what really propelled it into what became a mass movement was the explosion of punk’, although it wasn’t just about music. Huddle notes that

What also gave RAR the political context to become much bigger was the

establishment of the Anti Nazi League in 1977. Together the ANL and RAR were

able to build a really mass movement against the Nazis. The carnival in Victoria

Park with the Clash, Tom Robinson and Steel Pulse attracted 85,000, and received

fantastic coverage in NME. Twenty five thousand came to the Northern Carnival

in Manchester, which had The Buzzcocks, Graham Parker and the Rumour, and

Misty in Roots. The Brockwell Park event with Elvis Costello and Aswad had

100,000, and 26,000 heard Aswad and The Specials in Leeds.

In addition to the big events mentioned above, there were also local gigs, stickers, posters and placards, rallies and marches. It was a long way from Trafalgar Square to Victoria Park, and the march went through areas that were considered NF strongholds at the time, and verbal abuse and fighting ensued. [3]

Syd Shelton joined RAR in early 1977. Both of the books being reviewed contain his photographs ‘produced for and about’ the organisation, work which editor Carol Tulloch calls ‘a socialist act’. ‘His contribution to RAR was to be on the London committee, to create graphic material with other RAR members such as the RAR publication “Temporary Hoarding”, posters, badges and his photography’. Her co-editor Mark Sealy suggests that the photographs themselves, gathered up for publication here, ‘enable us to feel the ferocity of cultural difference being hammered out on Britain’s streets’, and mark ‘an intriguing, fragile and volatile political movement that literally changed the world’.

But one thing RAR wasn’t, and that Shelton’s photos bear witness to, is po-faced or dull. Shelton himself, in an interview with Adam Phillips included in the Rare Bird book, says that he ‘like[s] to think that RAR had more in common with the Dadists in Zurich than a political party’ and notes that ‘the other thing that was really important was, as David Widgery said brilliantly, “The great thing about RAR was it’s a way of having a revolution without stopping the party.”‘

Part of that ability to have fun and party, in addition to the music, says Shelton, was that RAR was ‘very much a collective’, ‘a collective of activists’ where there was ‘an argument constantly going on’. In the same interview he later extends that idea of dialogue to how he thinks about photography as a relationship, ‘the conversation you have, visual conversation often, not necessarily speaking, the conversation between me and the subject’, and also notes that ‘for a few short years there was an incredible empowerment’ and that his ‘photographs of this period are about my life as well as about the subject’s life’.

The RAR team at the time of course, ‘had no idea of either its significance historically or how much effect it was having on people. […] we didn’t have time to stand back and assess it in anyway at all.’ Now, however, we all can: this is history that is more relevant than ever as racism and intolerance resurface. Shelton thinksa that ‘thirty five years later we look at the images in a very different way and many of the photographs in the book never saw the light of day in the 1970s’, whilst Paul Gilroy, in his more academic essay, declares the images are the product of ‘nostalgia-free lenses’ and that ‘Shelton’s archive is also a means by which to grasp the strategic significance of anti-racism and to understand its value as both a substantive political disposition and a grounded philosophical framework.’

Although, as Gilroy suggests, ‘[r]acism has changed and yet remains with us’, these photographs offer what he calls ‘expanded conceptions of what comprises authentic politics and of where cultural factors have decisively shaped important outcomes.’ The images are themselves political, Gilroy argues, documenting a period when ‘[a]morphous, generalized dissent started to assume solid shapes. It became recognisable as more than trivial and ephemeral. Anti-racism could supply the futures that were being denied by bleak historical circumstances.’

Even though it defeated the National Front, RAR didn’t stop Thatcher coming to power or the rise of neo-liberalism, Gilroy suggests that ‘Shelton’s images conjure up a rebel history that enriches analysis of Britain’s class struggles and socialist movements.’ Or, as Shelton himself puts it, ‘I’d like people to see hope. I’d like them to see that Black and white youth did have a vision for a better way of living in this country and that we could actually change things.’

The Café Royal book is an exquisitely produced black and white booklet that mostly features musicians in action. In between Paul Simonon of the Clash playing to the crowd on the front cover and a thoughtful Dennis Brown in Berry Street Studios on the back, we find Elvis Costello, the Barry Forde Band, Misty in Roots, The Beat, a distant shot over the crowd of the Tom Robinson Band, Leslie Woods from the Au Pairs, Stiff Little Fingers, a puzzled looking Jimmy Pursey, Mick Jones and Paul Simonon backstage, Fergul Sharkey, Skully Roots, Ranking Roger, The Ruts, The Specials, Pete Townsend, The Clash (again!), Generation X and Sham 69, Aswad and The Members. And across the centre double page spread is Tom Robinson on stage at Victoria Park, dressed in his own band t-shirt, hands raised to the huge crowd. It’s an iconic image, and a reminder that it wasn’t just racism RAR were fighting, it was any discrimination based on difference. It was quite a statement when the majority of people at Victoria Park sang Robinson’s ‘Glad to be Gay’ at the top of their voices.

The Rare Bird book is more substantial, has those contextualising essays I’ve quoted from above, and feels very different. It’s expansive, wide-ranging and contextualises the activities of RAR and the Anti-Nazi League with photographs of the crowd, graffiti, the streets, shops and the semi-derelict or abandoned places where kids or lovers hung out. There’s attitude, posing and anger; barbed wire and stray dogs, unloved blocks of flats, and people chilling and drinking. It’s odd to be reminded of how we all dressed back then, how most people still had longish hair and wore flares, and that punks, skins and Rastas were minority presences in the overall scheme of things, even when it came to youth subcultures and fashion.

I loved living in London in the late 70s. It was vibrant, energetic and possible to live cheaply, go to loads of gigs and the cinema, despite strikes, blackouts and the frequent sense of not always suppressed anger and violence. Urban decay, failing social and business infrastructures, and poverty hadn’t got in the way of new music, in fact it helped facilitate it; and young people seemed both politically aware and active. Meanwhile, says Saunders, ‘RAR was using the simple but explosive idea that by bringing Black and White musicians together to challenge Britain’s default racism, we could dream to change the world by using Music and Politics to fight Racism.’ Perhaps it’s time to be inspired again and try to change the world once more?

Rupert Loydell

NOTES

[1] The full text of Powell’s speech, along with a recording of it, is available as part of the online documentation from the Dispatches: Society episode ‘Immigration: The Inconvenient Truth’ at https://www.channel4.com/news/articles/dispatches/rivers%2Bof%2Bblood%2Bspeech/1934152.html

[2] See ‘The “Great Replacement” Theory, Explained’ at https://immigrationforum.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/Replacement-Theory-Explainer-1122.pdf

[3] Alan Miles’ 2005 Rock Against Racism documentary, Who Shot the Sheriff includes footage from the London rally, march and the Victoria Park carnival, as well as other RAR events, along with interviews with Red Saunders, Roger Huddle. It’s available at https://vimeo.com/11494489