Origins are important. They are what the important words are about. Place names. The names of the rivers are older than the towns. In folk music, it is the older, bottomless ballads that draw and haunt you. The Elfin Knight, Lord Randall, Lord Bateman, The Jew’s Garden, ballads of fairy lore like Tam Lyn… That Bob Dylan quote from the 60s: “There’s nobody that’s going to kill traditional music… All these songs about roses growing out of people’s brains and lovers who are really geese and swans that turn into angels… they’re not going to die.”

Traditional songs are the free radicals in the imaginative genome, tales that twist and turn like mitochondrial DNA, pumping out a body of metaphor, allegory, symbolism and riddle. Is metaphor the oldest tool in the human pack? Older than the wheel, than flint, fusing one realm with another to create a third reality, images that change the shape of a room, all contained in the mouth, rolling over and over in the sea of the unconscious. The first human tool was to conceive.

Moving slowly under that moment in Dad’s study when I read Brendan Quinn’s name on my birth certificate for the first time was the long search for origins, the probe into the fleshy past of the mind’s eye and the soil beneath the root. In time it would become a driving force in my imaginative life, and for much of my lived one, the adopted life. The further away from childhood, the stranger the world is for the adoptee. Who the hell was Brendan Quinn anyway? Here he is stumbling out of an Irish bar on Holloway Road, late 1980s, following the double, looking for the other half, the first Eve. What he couldn’t help seeing was the after-image of the birth mother leaving him behind in the nursery at Coleshill. Did she stop and look back? And did those feet in ancient times? And did she turn to stone?

When I looked at stars through a telescope, I knew I was seeing into the deep past, way beyond the human realms and the studded dome of the skull. And if I looked around me, past the bungalows and traffic, it was the rings and mounds and circles and tumps that were the clitter of the Wessex landscape and the child’s mindscape, as if a lost child’s imagination was a binding plant with roots in the earth, for I was a little lost, I think.

Mum and Dad were big walkers and we walked with them, straggling behind. Long before the Peace convoy came to Stonehenge, we’d drive up there in the family VW, park up off the road, I’d climb out of the back with the family dog into the strong wind, among tall grasses whiplashed across Salisbury Plain, the sky above as heavy as the clay beneath. Somewhere on Dad’s 8mm reels of film, now on a high shelf in my upstairs office, is a sequence of me and my brothers clambering on the altar stone, the sacrifice stone that Hardy wrote for Tess of the D’Urbervilles. It’s a clip I haven’t found yet, but it’s something I know is always there, the Drewdrop Inn in the vale of the little dairies. The summer after I turned 16, we moved to the edge of the Blackmore Vale, undulating between the Cranborne Chase and Bulbarrow Hill in Thomas Hardy’s dreamtime.

I’ve drunk at the Drew Drop, and walked the desolate slopes where Tess wintered on desolate fields, pulling root vegetables from frozen clay. Nearby’s the Hand and Cross, a lone and ancient standing stone some three feet high. If it was ever a cross, the arms are long gone. Beneath, so lore has it, a murderer’s hands are buried. The nameless criminal was tortured and hung on a gibbet from this lonely place. There are dank, rotting woods nearby, bare clay fields nurturing a colourless winter crop, a bridleway to the east, and the steepest of lanes plunging down to richer lands, towards Cerne Abbas and the priapic giant, his erection sticking up to his belly button. Walking down the steep and shady hill was almost folkloric in itself. That is, you expressed it as you descended and it said something to you.

I tuned into traditional songs early on. They were like marsh lights on the same track that fairy tales and nursery rhymes came from. I could identify. I didn’t know where I came from, and the origins of the songs were as obscure as my own. Whose authorship? You knew that once they were they, they had always been there. You could tell this was massive, accumulated baggage. They had the gravitational pull of the large planets. The tunes charmed something vital from the mouth, and from the insides, the stuff of Elizabethan metaphysics with its gods, daemons and aeythrs. I soaked up the old riddling ballads, the tale of the outlandish knight – the water sprite lurking in the heart, not the head or the crown, of the tale. The outlandish knight seemed so old he could’ve sported gills and a tail. Years later, in a second-floor room of a folk music centre in Cairo, I’d hear at first-hand the high, silver sound of the simsimiyah lyre that had once played before the Pharoahs, a spirit medium carved into friezes at Luxor that came to life in the hands of my host Zakaria, with a fast, high, quicksilver sound.

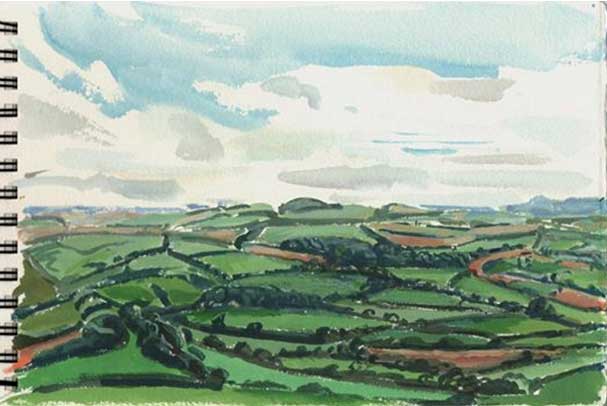

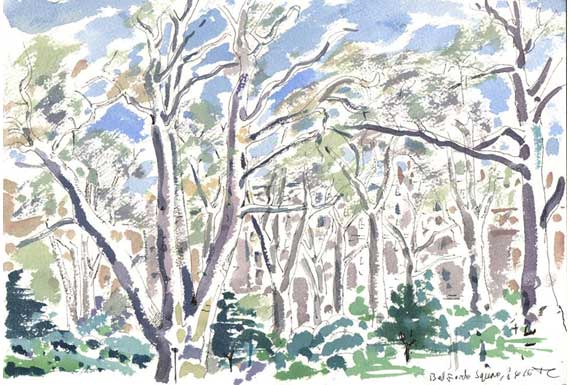

How old was the oldest tune? Did we sing before we spoke, and dance before we sang? They say there’s a carving of a Mycenaean dagger on one of the sarsens at Stonehenge. So what exchange was really going on? Clambering across the altar stone as a child, I felt myself stretch in time. Escapism, of course. Just my imagination. But how far did I want to go? Until the images became clear. I remember slipping into dad’s studio to look at the new work, the spell of fresh paint and turpentine, like the smell of a new universe being born. It was entrancing, how he could orchestrate a few marks that, close up, were mere brushstrokes, blobs on canvas, accidents, until you stepped back. Perhaps three paces, a dueller’s distance. Look again, and the rich, far distances of England leap into being. It was a magical act I never tired of. Just step back. I think there’s a model for consciousness there, a lesson to be had in being too close to be able to see it, so all you can see is fabric – the grain of the canvas, the heft of the hogs’ hair spreading and shaping and graining the paint. All this colour animated into a living being by a change in perspective, the pattern in the carpet – just a few steps back. The right point of view is an art form in itself.

I painted before I could talk, and I still paint, sometimes more than I talk, and when I look at dad’s paintings now, I retreat further back down the passage and take the left fork into the darkness, now that dad is dead, finding his level with all the image makers. His prices at auction, I notice, are going up. Do painters turn to pigment when they die? Sometimes you have to be at the right distance from the beginning of things.

From childhood memories poured and stirred around family mealtimes, I can see the placemats depicting late Paleolithic figures – dancing hunters and bison, horses and ibex – at which we ate at our fixed constellation of family seating. As painters who knew their craft, lived their art and taught it well, mum and dad had the highest regard for these early image makers. They knew it couldn’t be bettered. I recognise now that those placemat figures were copies from the caves at Altamira in Spain. When Marcelino Sanz de Sautuola was led by his nine-year-old daughter to see the bisons on the ceiling of the caves on his land in 1879, his assertation that they were by Stone Age man was ridiculed and his reputation ruined. He was accused of forgery. Not one expert in the field believed Stone Age man capable of such a feat. And so, over the decades, the set was pushed further back. Four little boys – Marcel, Jacques, Georges, Simon and their dog Robot – crawled through the cave mouth into Grotte Lascaux in the first autumn of the war, 1940, following the trail of a local legend of an old tunnel leading to hidden treasure. The dog found the hole first, sniffing out its scent, and the boys slid down the 15 metres of a shaft to a dark underground chamber. ‘The descent was terrifying,’ said Marsal, the youngest, and in the light of an oil lantern, they looked around them. What they saw, Marsal remembered, was ‘a cavalcade of animals larger than life painted on the walls and ceiling of the cave; each animal seemed to be moving.’

Imagine the first shock of recognition when the cave art at Chauvet, some 200 kilometres east of Lascaux, on the limestone cliffs of the Gorge of the Ardeche, was exposed to artificial illumination and human consciousness for the first time in millennia. Chauvet, we are told, houses the oldest known figurative paintings in the world, though even as I write, Neanderthal paintings from 100 millennia earlier have been identified. The images are of seals, one on top of another, though they do resemble the blurred shadow of our modern image for DNA.

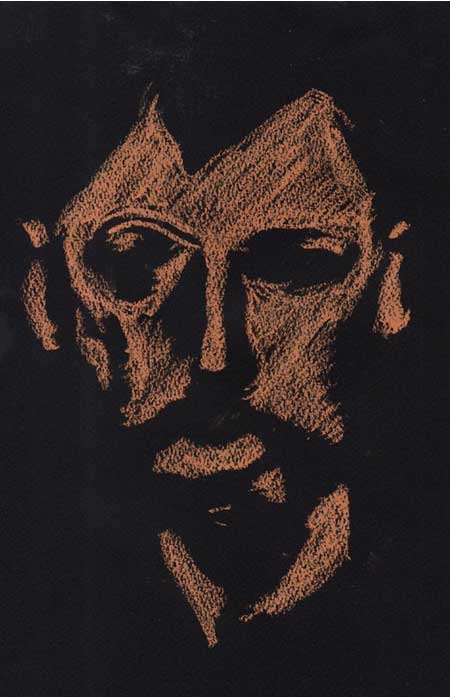

In Britain, our oldest cave art is a faint outline of an antlered stag at Creswell Crags, the name for a system of caves on the borders between Nottingham and Derbyshire that sheltered humans in Britain at the end of the last Ice Age. Creswell Crags dates from around 12,000BC. A wooden spear at Margate was last thrown around 400,000BC. What were we thinking between times? What made us want to make a mark? I started making my first marks with pigment in 1965. A portrait of my dad done at nursery school hung by the backdoor to the family home all the time we were there. I still have it. That thin primary school paper is like a membrane, somewhere in the world to stick your fingers through.

In the story of Chauvet, the important date is 18th December 1994. Dad had died the previous summer, and that winter I had drafted a letter to the children’s home. I kept it in my bag, carried it like a weapon or a curse through the streets and tributaries of north London. Here is Jean-Marie Chauvet, who discovered the caves, many hundreds of miles from north London, recalling the impact of stumbling upon those long-forgotten images for the first time. “Time was abolished, as if the tens of thousands of years that separated us from the producers of these paintings no longer existed. Deeply impressed, we were weighed down by the feeling that we were not alone; the artists’ souls and spirits surrounded us. We thought we could feel their presence; we were disturbing them.”

Radiocarbon dates suggest that Chauvet contains the oldest Paleolithic cave art yet discovered – dating back some 35,000 years. Veiled for much of the year in pitch darkness, images common to all European cave art – mammoths, reindeer, horses, cattle, as well as hand prints and hand silhouettes – float among rarer cave beasts: bears, lions, hyenas, an owl – its head turned 180 degrees. There is a bear’s skull on a stone ‘altar’, and in the deepest part of the cave, in the ‘Sorcerer’s chamber’, a half-man, half-bison figure leaps out of the rock, paired with an older depiction of a woman, her thighs and sex organs strongly accentuated. Sex, fertility, bears.

We can never know what power these figures exerted on their makers; our closest resource is, perhaps, the power they retain over us and how that power changes over time, with ways of seeing. I look down at the ghost image of paleolithic placemats at the family table, the constellation of family seating, the colour of the images still living and wet in the patterning mind. And at the edge of vision, the birth certificate for Brendan Quinn, a version of me that existed only as pigment on a surface, like those hand prints at Chauvet.

It was midwinter, and I had arranged to meet an archaeologist from Johannesburg with an interest in altered states. He had just come from the caves at Mas D’Azil in the Pyrenees – “squeezing and crawling through, and as you lie in the tunnel, right above you there are the engravings.” He pauses, breathing heavily through a winter fever, or in remembering his descent. “What were these people up to? Why did they feel they had to crawl all these distances to make their images? What were they doing down there?’ He shakes his head. ‘I think the only answer is that they did it because that’s where the images were. They were looking for them. They thought these images were deep underground.”

We’re talking over coffee and biscuits in the dining room of a grand hotel near Russell Square on a miserable winter afternoon, midweek, the lights of the traffic runny in artificial light. The dining room is empty apart from ourselves, and there are no paintings on the wall. As we talk, he admits to an appalling cold, and I see an otherworldly glitter in his eye that I take for fever rather than disposition. Late middle age, glasses, side parting, thin hair. A faint cross-hatch pattern on his beige jacket. You could imagine a figure like his stepping from the British Museum on a gusty cold December’s gloaming and unexpectedly encountering on old acquaintance in much reduced circumstances in a story by Arthur Machen, Britain’s greatest writer of weird fiction. Machen conjured mystery and imagination from the London labyrinth, and it wasn’t just in the gas-lit upper rooms of 1840s Soho, the clubs along the Strand, or the suburbs of Acton or Barnet or Enfield Lock, but everywhere, inescapably as rich in mysteries as Luxor and as close to hand as the 38 bus. Machen’s London was a walking city of shifting intimations, stage curtains, synchronicity and intrigue.

With his stories carrying on by themselves in my head, I bid farewell to the professor, doubting that we would meet again in this life, and plunged back into the late afternoon light, gulping in cold and cloudy air. I had a small joint of excellent Nepalese hashish in my jacket pocket, and in my head the image of a pregnant ibex carrying her young across a stream in a Stone Age carving on an antler bone in Room One of the British Museum. I’d stopped there an hour before our meeting, astonished before the glass case for half my visit, then peeling off to inspect the scrying ball of Edward Kelley and Dr Dee. It was tiny, about the same size as the hypnagogic images that sometimes flocked about my closed eyes before sleep. I’d leant forward and told Dr Lewis-Williams about my hypnogogia – involuntary images flocking to the wire, of crowd scenes, and human heads that change into bears, and wolves, and reptiles, and back towards the primeval sludge that haunted Machen. Lovecraft, too. The Color Out of Space. The professor looked at me warily, and said he looked forward to reading my article.

The streetlights were coming on, and there was only a light drizzle. The ibex, I noticed, swam beside me as I crossed Russell Square and cut down towards Queen’s Square to smoke my stick of Nepalese under the statue of Queen Charlotte, wife to Mad King George. I thought about what I knew.

The professor had stuck his flag into the role of altered neurological states as the reason behind the making and meaning of Paleolithic art. 35,000 years on, with whatever means were at our disposal, we were still charting the alterations. While neurologists studied scans of oxygenated blood as if they were a vulture’s entrails, the matter of mind remained elusive, unapproachable, the ibex forever swimming mid-stream with its young on its back. Metaphor says more about mind than math.

At Chauvet, as in many other locations, the bestiary is accompanied by abstractions and scorings – spots, lines, zigzags, grids, circles – the kind of visual interference associated with accounts of trance and altered states. These, in turn, gave way to images of animals – largely the same repertoire for many millennia – that were long held in the mind before they appeared, seemingly fully formed, on the cave wall. Like Orpheus, our Paleolithic painters journeyed deep underground, into the very entrails of the underworld, spotting the forms of animals emerging from cracks and protuberances in the rock. That rock face acted as a membrane to a supernatural world that was held in the mind of shamanic figures. Was that membrane with us now, I thought. Where in the world could you push your fingers through to feel what was happening on the other side? It was like trying to feel yourself with someone else’s hands.

Was this the point of origin I was searching for; the long prologue? When could I descend the long-occulted chamber? What astonishes most is that Chauvet’s cave complex held an image tradition that, with minor modulations, would continue unchanged for many thousands of years, their potency on the eye evidently undimmed, their kinetic impact disarmingly fresh. That was the kind of depth I needed to go.

What were those meanings that persisted for so long? What was their purpose? Why were people compelled to journey up to a kilometre underground to make and to see? It is one of archaeology’s – and humanity’s – great mysteries. It was once thought to be an example of sympathetic magic – rendering your hunting goal then go-getting it. But many of the animals are not those they actually hunted. And if they were the totems of a unifying religion, why is the art in such inaccessible places?

Though no musical instruments have been found at Chauvet, we do know that music was made in the caves. Evidence has been found of stalactites being struck to make resonant gong-like sounds, and flutes hollowed from birds’ wings, bone and ivory have been found embedded in cave floors. When one of them was reconstructed, it played the diatonic scale of Do Re Mi. And this from a Neanderthal flute. An old tune heard long ago. And so our vast timescale evaporates in the sound of music, and the pigments of the Palaeolithic palette. See their work, and it’s almost as if they’re still among us, the way Jean-Marie Chauvet felt on first encountering the images on the cave wall, when he thought he could feel their presence, and that he had disturbed them.

Origins are important. They are what the important words are about. Place names. The names of the rivers are older than the towns. In folk music, it is the older, bottomless ballads that draw and haunt you. The Elfin Knight, Lord Randall, Lord Bateman, The Jew’s Garden, ballads of fairy lore like Tam Lyn… That Bob Dylan quote from the 60s: “There’s nobody that’s going to kill traditional music… All these songs about roses growing out of people’s brains and lovers who are really geese and swans that turn into angels… they’re not going to die.”

Traditional songs are the free radicals in the imaginative genome, tales that twist and turn like mitochondrial DNA, pumping out a body of metaphor, allegory, symbolism and riddle. Is metaphor the oldest tool in the human pack? Older than the wheel, than flint, fusing one realm with another to create a third reality, images that change the shape of a room, all contained in the mouth, rolling over and over in the sea of the unconscious. The first human tool was to conceive.

Moving slowly under that moment in Dad’s study when I read Brendan Quinn’s name on my birth certificate for the first time was the long search for origins, the probe into the fleshy past of the mind’s eye and the soil beneath the root. In time it would become a driving force in my imaginative life, and for much of my lived one, the adopted life. The further away from childhood, the stranger the world is for the adoptee. Who the hell was Brendan Quinn anyway? Here he is stumbling out of an Irish bar on Holloway Road, late 1980s, following the double, looking for the other half, the first Eve. What he couldn’t help seeing was the after-image of the birth mother leaving him behind in the nursery at Coleshill. Did she stop and look back? And did those feet in ancient times? And did she turn to stone?

When I looked at stars through a telescope, I knew I was seeing into the deep past, way beyond the human realms and the studded dome of the skull. And if I looked around me, past the bungalows and traffic, it was the rings and mounds and circles and tumps that were the clitter of the Wessex landscape and the child’s mindscape, as if a lost child’s imagination was a binding plant with roots in the earth, for I was a little lost, I think.

Mum and Dad were big walkers and we walked with them, straggling behind. Long before the Peace convoy came to Stonehenge, we’d drive up there in the family VW, park up off the road, I’d climb out of the back with the family dog into the strong wind, among tall grasses whiplashed across Salisbury Plain, the sky above as heavy as the clay beneath. Somewhere on Dad’s 8mm reels of film, now on a high shelf in my upstairs office, is a sequence of me and my brothers clambering on the altar stone, the sacrifice stone that Hardy wrote for Tess of the D’Urbervilles. It’s a clip I haven’t found yet, but it’s something I know is always there, the Drewdrop Inn in the vale of the little dairies. The summer after I turned 16, we moved to the edge of the Blackmore Vale, undulating between the Cranborne Chase and Bulbarrow Hill in Thomas Hardy’s dreamtime.

I’ve drunk at the Drew Drop, and walked the desolate slopes where Tess wintered on desolate fields, pulling root vegetables from frozen clay. Nearby’s the Hand and Cross, a lone and ancient standing stone some three feet high. If it was ever a cross, the arms are long gone. Beneath, so lore has it, a murderer’s hands are buried. The nameless criminal was tortured and hung on a gibbet from this lonely place. There are dank, rotting woods nearby, bare clay fields nurturing a colourless winter crop, a bridleway to the east, and the steepest of lanes plunging down to richer lands, towards Cerne Abbas and the priapic giant, his erection sticking up to his belly button. Walking down the steep and shady hill was almost folkloric in itself. That is, you expressed it as you descended and it said something to you.

I tuned into traditional songs early on. They were like marsh lights on the same track that fairy tales and nursery rhymes came from. I could identify. I didn’t know where I came from, and the origins of the songs were as obscure as my own. Whose authorship? You knew that once they were they, they had always been there. You could tell this was massive, accumulated baggage. They had the gravitational pull of the large planets. The tunes charmed something vital from the mouth, and from the insides, the stuff of Elizabethan metaphysics with its gods, daemons and aeythrs. I soaked up the old riddling ballads, the tale of the outlandish knight – the water sprite lurking in the heart, not the head or the crown, of the tale. The outlandish knight seemed so old he could’ve sported gills and a tail. Years later, in a second-floor room of a folk music centre in Cairo, I’d hear at first-hand the high, silver sound of the simsimiyah lyre that had once played before the Pharoahs, a spirit medium carved into friezes at Luxor that came to life in the hands of my host Zakaria, with a fast, high, quicksilver sound.

How old was the oldest tune? Did we sing before we spoke, and dance before we sang? They say there’s a carving of a Mycenaean dagger on one of the sarsens at Stonehenge. So what exchange was really going on? Clambering across the altar stone as a child, I felt myself stretch in time. Escapism, of course. Just my imagination. But how far did I want to go? Until the images became clear. I remember slipping into dad’s studio to look at the new work, the spell of fresh paint and turpentine, like the smell of a new universe being born. It was entrancing, how he could orchestrate a few marks that, close up, were mere brushstrokes, blobs on canvas, accidents, until you stepped back. Perhaps three paces, a dueller’s distance. Look again, and the rich, far distances of England leap into being. It was a magical act I never tired of. Just step back. I think there’s a model for consciousness there, a lesson to be had in being too close to be able to see it, so all you can see is fabric – the grain of the canvas, the heft of the hogs’ hair spreading and shaping and graining the paint. All this colour animated into a living being by a change in perspective, the pattern in the carpet – just a few steps back. The right point of view is an art form in itself.

I painted before I could talk, and I still paint, sometimes more than I talk, and when I look at dad’s paintings now, I retreat further back down the passage and take the left fork into the darkness, now that dad is dead, finding his level with all the image makers. His prices at auction, I notice, are going up. Do painters turn to pigment when they die? Sometimes you have to be at the right distance from the beginning of things.

From childhood memories poured and stirred around family mealtimes, I can see the placemats depicting late Paleolithic figures – dancing hunters and bison, horses and ibex – at which we ate at our fixed constellation of family seating. As painters who knew their craft, lived their art and taught it well, mum and dad had the highest regard for these early image makers. They knew it couldn’t be bettered. I recognise now that those placemat figures were copies from the caves at Altamira in Spain. When Marcelino Sanz de Sautuola was led by his nine-year-old daughter to see the bisons on the ceiling of the caves on his land in 1879, his assertation that they were by Stone Age man was ridiculed and his reputation ruined. He was accused of forgery. Not one expert in the field believed Stone Age man capable of such a feat. And so, over the decades, the set was pushed further back. Four little boys – Marcel, Jacques, Georges, Simon and their dog Robot – crawled through the cave mouth into Grotte Lascaux in the first autumn of the war, 1940, following the trail of a local legend of an old tunnel leading to hidden treasure. The dog found the hole first, sniffing out its scent, and the boys slid down the 15 metres of a shaft to a dark underground chamber. ‘The descent was terrifying,’ said Marsal, the youngest, and in the light of an oil lantern, they looked around them. What they saw, Marsal remembered, was ‘a cavalcade of animals larger than life painted on the walls and ceiling of the cave; each animal seemed to be moving.’

Imagine the first shock of recognition when the cave art at Chauvet, some 200 kilometres east of Lascaux, on the limestone cliffs of the Gorge of the Ardeche, was exposed to artificial illumination and human consciousness for the first time in millennia. Chauvet, we are told, houses the oldest known figurative paintings in the world, though even as I write, Neanderthal paintings from 100 millennia earlier have been identified. The images are of seals, one on top of another, though they do resemble the blurred shadow of our modern image for DNA.

In Britain, our oldest cave art is a faint outline of an antlered stag at Creswell Crags, the name for a system of caves on the borders between Nottingham and Derbyshire that sheltered humans in Britain at the end of the last Ice Age. Creswell Crags dates from around 12,000BC. A wooden spear at Margate was last thrown around 400,000BC. What were we thinking between times? What made us want to make a mark? I started making my first marks with pigment in 1965. A portrait of my dad done at nursery school hung by the backdoor to the family home all the time we were there. I still have it. That thin primary school paper is like a membrane, somewhere in the world to stick your fingers through.

In the story of Chauvet, the important date is 18th December 1994. Dad had died the previous summer, and that winter I had drafted a letter to the children’s home. I kept it in my bag, carried it like a weapon or a curse through the streets and tributaries of north London. Here is Jean-Marie Chauvet, who discovered the caves, many hundreds of miles from north London, recalling the impact of stumbling upon those long-forgotten images for the first time. “Time was abolished, as if the tens of thousands of years that separated us from the producers of these paintings no longer existed. Deeply impressed, we were weighed down by the feeling that we were not alone; the artists’ souls and spirits surrounded us. We thought we could feel their presence; we were disturbing them.”

Radiocarbon dates suggest that Chauvet contains the oldest Paleolithic cave art yet discovered – dating back some 35,000 years. Veiled for much of the year in pitch darkness, images common to all European cave art – mammoths, reindeer, horses, cattle, as well as hand prints and hand silhouettes – float among rarer cave beasts: bears, lions, hyenas, an owl – its head turned 180 degrees. There is a bear’s skull on a stone ‘altar’, and in the deepest part of the cave, in the ‘Sorcerer’s chamber’, a half-man, half-bison figure leaps out of the rock, paired with an older depiction of a woman, her thighs and sex organs strongly accentuated. Sex, fertility, bears.

We can never know what power these figures exerted on their makers; our closest resource is, perhaps, the power they retain over us and how that power changes over time, with ways of seeing. I look down at the ghost image of paleolithic placemats at the family table, the constellation of family seating, the colour of the images still living and wet in the patterning mind. And at the edge of vision, the birth certificate for Brendan Quinn, a version of me that existed only as pigment on a surface, like those hand prints at Chauvet.

It was midwinter, and I had arranged to meet an archaeologist from Johannesburg with an interest in altered states. He had just come from the caves at Mas D’Azil in the Pyrenees – “squeezing and crawling through, and as you lie in the tunnel, right above you there are the engravings.” He pauses, breathing heavily through a winter fever, or in remembering his descent. “What were these people up to? Why did they feel they had to crawl all these distances to make their images? What were they doing down there?’ He shakes his head. ‘I think the only answer is that they did it because that’s where the images were. They were looking for them. They thought these images were deep underground.”

We’re talking over coffee and biscuits in the dining room of a grand hotel near Russell Square on a miserable winter afternoon, midweek, the lights of the traffic runny in artificial light. The dining room is empty apart from ourselves, and there are no paintings on the wall. As we talk, he admits to an appalling cold, and I see an otherworldly glitter in his eye that I take for fever rather than disposition. Late middle age, glasses, side parting, thin hair. A faint cross-hatch pattern on his beige jacket. You could imagine a figure like his stepping from the British Museum on a gusty cold December’s gloaming and unexpectedly encountering on old acquaintance in much reduced circumstances in a story by Arthur Machen, Britain’s greatest writer of weird fiction. Machen conjured mystery and imagination from the London labyrinth, and it wasn’t just in the gas-lit upper rooms of 1840s Soho, the clubs along the Strand, or the suburbs of Acton or Barnet or Enfield Lock, but everywhere, inescapably as rich in mysteries as Luxor and as close to hand as the 38 bus. Machen’s London was a walking city of shifting intimations, stage curtains, synchronicity and intrigue.

With his stories carrying on by themselves in my head, I bid farewell to the professor, doubting that we would meet again in this life, and plunged back into the late afternoon light, gulping in cold and cloudy air. I had a small joint of excellent Nepalese hashish in my jacket pocket, and in my head the image of a pregnant ibex carrying her young across a stream in a Stone Age carving on an antler bone in Room One of the British Museum. I’d stopped there an hour before our meeting, astonished before the glass case for half my visit, then peeling off to inspect the scrying ball of Edward Kelley and Dr Dee. It was tiny, about the same size as the hypnagogic images that sometimes flocked about my closed eyes before sleep. I’d leant forward and told Dr Lewis-Williams about my hypnogogia – involuntary images flocking to the wire, of crowd scenes, and human heads that change into bears, and wolves, and reptiles, and back towards the primeval sludge that haunted Machen. Lovecraft, too. The Color Out of Space. The professor looked at me warily, and said he looked forward to reading my article.

The streetlights were coming on, and there was only a light drizzle. The ibex, I noticed, swam beside me as I crossed Russell Square and cut down towards Queen’s Square to smoke my stick of Nepalese under the statue of Queen Charlotte, wife to Mad King George. I thought about what I knew.

The professor had stuck his flag into the role of altered neurological states as the reason behind the making and meaning of Paleolithic art. 35,000 years on, with whatever means were at our disposal, we were still charting the alterations. While neurologists studied scans of oxygenated blood as if they were a vulture’s entrails, the matter of mind remained elusive, unapproachable, the ibex forever swimming mid-stream with its young on its back. Metaphor says more about mind than math.

At Chauvet, as in many other locations, the bestiary is accompanied by abstractions and scorings – spots, lines, zigzags, grids, circles – the kind of visual interference associated with accounts of trance and altered states. These, in turn, gave way to images of animals – largely the same repertoire for many millennia – that were long held in the mind before they appeared, seemingly fully formed, on the cave wall. Like Orpheus, our Paleolithic painters journeyed deep underground, into the very entrails of the underworld, spotting the forms of animals emerging from cracks and protuberances in the rock. That rock face acted as a membrane to a supernatural world that was held in the mind of shamanic figures. Was that membrane with us now, I thought. Where in the world could you push your fingers through to feel what was happening on the other side? It was like trying to feel yourself with someone else’s hands.

Was this the point of origin I was searching for; the long prologue? When could I descend the long-occulted chamber? What astonishes most is that Chauvet’s cave complex held an image tradition that, with minor modulations, would continue unchanged for many thousands of years, their potency on the eye evidently undimmed, their kinetic impact disarmingly fresh. That was the kind of depth I needed to go.

What were those meanings that persisted for so long? What was their purpose? Why were people compelled to journey up to a kilometre underground to make and to see? It is one of archaeology’s – and humanity’s – great mysteries. It was once thought to be an example of sympathetic magic – rendering your hunting goal then go-getting it. But many of the animals are not those they actually hunted. And if they were the totems of a unifying religion, why is the art in such inaccessible places?

Though no musical instruments have been found at Chauvet, we do know that music was made in the caves. Evidence has been found of stalactites being struck to make resonant gong-like sounds, and flutes hollowed from birds’ wings, bone and ivory have been found embedded in cave floors. When one of them was reconstructed, it played the diatonic scale of Do Re Mi. And this from a Neanderthal flute. An old tune heard long ago. And so our vast timescale evaporates in the sound of music, and the pigments of the Palaeolithic palette. See their work, and it’s almost as if they’re still among us, the way Jean-Marie Chauvet felt on first encountering the images on the cave wall, when he thought he could feel their presence, and that he had disturbed them.

Tim Cumming