The Shepherd’s Hut, Tim Winton (Picador)

The main character in Tim Winton’s new novel is an unlikeable teenage ruffian, intent on escaping the legacy of his brutal father who has unexpectedly died. Jaxie heads off with a backpack and rifle, and the first half of this book is pretty much a survival story: mentally and physically, young Jaxie has to suddenly survive on his own. Later, when least expected (and where least expected: Jaxie is now on the edge of farming land as it turns into desert) he meets Fintan, a retired priest with a dodgy past, and eventually a kind of friendship is struck up. This friendship and Jaxie’s childish hope in a girl he thinks he is in love with, who might be waiting for him, are the sole glimmers of hope in over 250 pages of gruff, sweary, belligerent storytelling.

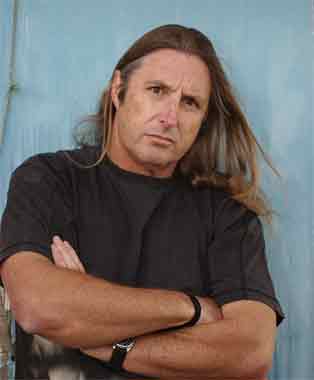

Winton, answering questions and talking about his writing at The Acorn in Penzance, is very much a ‘bloke’, but one who worries about what that means in the 21st century. Firmly rooted in North West Australia he talks about Jaxie arriving unannounced in his consciousness, insisting upon being written about; about how he had tried to inhabit the world of someone who cannot articulate their feelings, and lacks the language to do so. Jaxie’s vocabulary is limited, he speaks in the vernacular, and Winton starts the night by reading a tough passage where Jaxies recalls having to kill a sack full of kittens, upsetting at least one member of the audience who declares that, as a cat lover, she won’t be buying the new book.

Winton’s view of writing is quite romantic in many ways. The idea that a character ‘arrives’ and has to be inhabited and the world viewed through his or her eyes, is old school, like an actor becoming their character. Wyl Menmuir, the novelist hosting the evening, asks Winton about the ‘toxic masculinity’ evident in the book, which Winton has spoken about previously, and the context of the #MeToo movement. Winton is articulate and humble as he speaks about the macho culture he lives in but in many ways dislikes. He wants change but knows it is slow; is not egotistical enough to think a novel is going to change the world. He also turns it round, and says he wants to understand male culture and why it is like it is, and sees patriarchy letting go as the answer, that the world will be a much better place to live in if males step back from power and control and dominance.

Winton is no right-on PC crusader though. You can see him down the pub swearing at his mates, trying to convince them that change is needed, and in Penzance he constantly refers to his working class roots and the fact that people like him don’t go to university, write books, or travel thousands of miles to places like Cornwall. His success seems to somewhat bewilder him. He also talks about how change does occur, often when least expected, and that now might be the time the balance of power finally shifts. He’s seen things occur as the result of green and ecological campaigns, often overnight and out of the blue. And he seems to know how ironic all of this is. When asked by an earnest would-be writer about his writing routine, he laughs and reports that if it’s nice weather and the sea’s flat he goes out in his boat, if it’s nice and there’s a swell he goes surfing, if the weather’s shit then he makes himself write. Says that’s as much of a routine he can manage.

Still, including autobiographies and books for children, Winton has managed 29 books to his name, and clocked up a load of literary prizes whilst doing so. Cloudstreet is probably his most well known and well loved, an almost Dickensian tragi-comedy about two families sharing a big house. One family are hard-working and religious, the other lives by luck, allowing life to happen to them. In the middle of all this is the mentally disabled Fish, who sees visions and lives in a state of wonder and hope, sees another version of reality. For me, it is this (for want of a better word) spiritual underpinning, some notion of ‘grace’ perhaps, that is missing from The Shepherd’s Hut. Is friendship, which ultimately goes wrong for Jaxie and Fintan, or a teenage obsession about a female cousin, enough to redeem a character? Winton says he doesn’t have a sequel planned, and wasn’t interested in Jaxie suddenly changing for the better. Jaxie is who he is, and by understanding those who are different to us, and perhaps unable or unwilling to speak for themselves, we can learn and empathise, start a conversation. Winton’s book is harsh and depressing, yet a rough music underpins this visceral, masculine version of the world which Winton has chosen to articulate.

Rupert Loydell