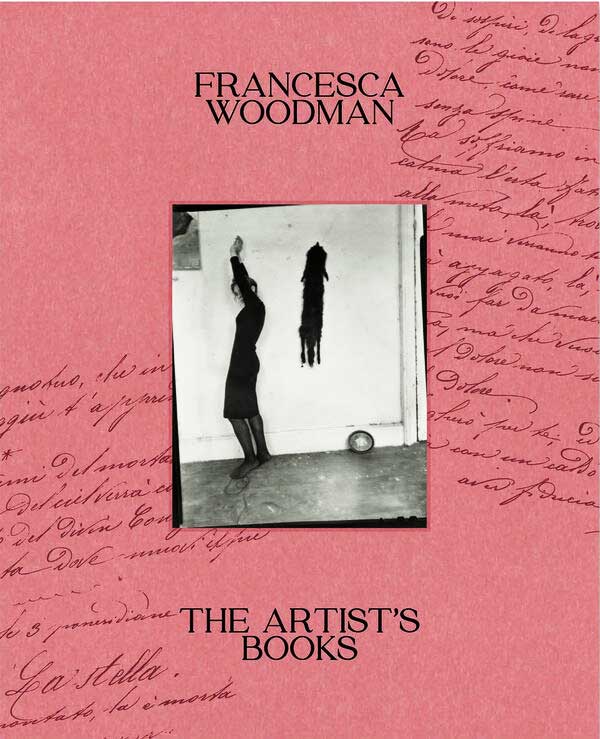

The Artist’s Books, Francesca Woodman (Mack)

Francesca Woodman was a young artist who killed herself in 1981, at the age of 22, in New York City. She left behind a now critically acclaimed body of photographic work which mostly depicted herself or female models often placed as part of the room. Sometimes blurred, sometimes unclothed, often folded into awkward poses or around furniture or fittings, the images are mostly unglamourous and alluring, suggestive of untold stories or hidden secrets.

In addition to the careful management of her five years of work by her parents (which resulted in major exhibitions at the San Francisco’s Museum of Modern Art and the Guggenheim in New York), word-of-mouth and feminist critique have built up a somewhat cult-like posthumous fame, with Woodman joining the ranks of struggling female artists who lost the fight with the patriarchal art establishment. Woodman is in the canon now, up there with Sylvia Plath and Ann Sexton, as abused, suicidal, ignored creatives.

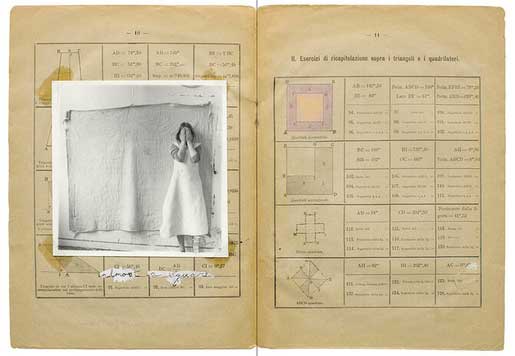

Now, Mack have published an exquisitely produced hardback book which shows Woodman’s working in a different way: creating artist’s books. Found books, such as business ledgers or old journals, are used as a ground for photographs, negatives (or prints on acetate), as well as found images and writing, resulting in highly personal, evocative and sparse one-off folios.

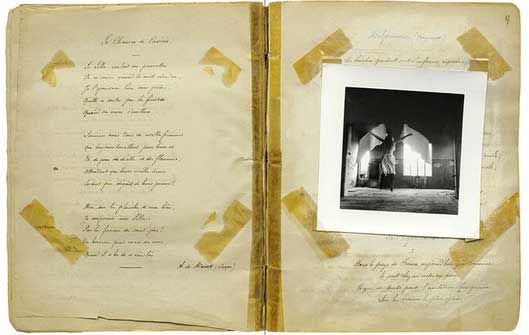

These assembled and curated albums are fragile journals, which arrange evocative images of architecture, human bodies and interior space, into loose yet obsessive clusters and sequences. Much of each book (there are eight collected in this volume) remains either empty or left as found – beautiful inked scripts, folds and stains, fading lines – with occasional photographs glued or sellotaped in, and even scarcer annotations and notes.

If anything, this all adds to the strangeness of the photographs. Why are the photos of a blurred woman jumping or dancing in a loft space made even more otherwordly because of the aged sellotape which fixes it to the chosen page and the sellotape stains on the page opposite, which reflect the form? What does the handwritten text already in the book do to the way we see the work? Why are some pictures a different size to the others in the same series or sequence? Why is the top third of one image dark? And why does the umbrella leant against a wall draw the attention of the viewer much more than the abstracted breasts of the model who fills the foreground at the bottom of the photo?

The marked pages and occasional empty photo mounts, the creases and unchanged pages are not questions that can be answered, or puzzles that can be assembled or decoded. They are enigmatic and personal, and we do not know if the work gathered here were intended as ‘artist’s books’, or as workbooks, a way of thinking about order and sequencing work-in-progress. They are both impersonal and highly personal, the artist distant from yet also very present in her work at the same time. The often gnomic phrases and occasional lists add to the tentative feel of these assemblages.

For me, there are few points of artistic reference for Woodman’s work. Occasionally, her naked bodies remind me of Andre Kertesz’s ‘distortions’, and sometimes the soft-focus strangeness and sense of surrealism seems to give a nod to fashion photographer Deborah Turbeville, whose name is mentioned once in the pages of these artist’s books. The photos are small-scale, intimate, images which invite the viewer in; they do not shock or shout, hector or cajole, they veer towards polite mumbling and softly spoken seduction.

When I first received this book I thought how strange it was to have the whole of each of Woodman’s books reproduced even when there was ‘nothing to see’. Several weeks later, I can appreciate that they have been very deliberately left as found by the artist, adding a different sense of texture, speed and density to the work. This is a strange and enigmatic publication, that will only add to the allure and reputation of Francesca Woodman’s all too brief engagement with the visual.

Rupert Loydell

Photos by MACK