Should Shelley, still not believing in God

(But still perhaps believing in daemons),

Walk down Oxford’s High Street to the former site

Of Slatter & Munday’s bookshop,

He’d find in its place a branch of Lloyds TSB –

A fluorescent temple to the Golden Calf;

No letterpress pamphlets lovingly sewn, but colour brochures

Inviting conversion to the bankers’ religion.

For instead of Shelley there are now display panels

To interest passers-by in interest rates;

With Cash Points proving the existence of the money god

Whose religion’s compulsory, even for atheists.

The first thing to greet visitors at Oxford station

(Expecting gentle scholars or a Jude the Obscure),

Is a starkly designed business school for the money-cult’s acolytes

Built by an arms-trader billionaire.

It’s succeeded by spiny fortresses plying for business by boasting

Of their success in producing government elites –

For each Oxford college lures the gullible into spending their life

Paying off loans to buy Oxford’s trade secrets.

Mammon stifles the dreams of the dreaming spires –

For its turreted antennae are tuned to investment

Ensuring scholarship for its own sake is thought redundant,

Unless it’s sold with a business model;

And the soulful shops that Oxford once had

Devoted to vinyl and second-hand books

Are priced out by chains selling sweatshop products –

Due to ‘progressive’ councils favoring clone-towns.

In ‘Queen Mab’ Shelley singled out “Selfishness!”

As “Twin-sister of Religion”,

To him selfishness was the great delusion’s companion –

Its “Rival in crime and falsehood.”

Then as now Mammon keeps such selfishness supplied

With tricks for storing up treasure on earth:

Mammon’s sly deceivers with their gilt-edged serpent

In fake Edens concocted from debt.

Economic charlatans who claim to see the future

And market a financial pie in the sky,

Only to dash peoples’ hopes as their coins dwindle away,

For “There is no real wealth

But the labor of man”11 – as the student whom Oxford spurned,

Oxford’s socialist anarchist, once said,

Before adding, “The man of virtuous soul,

Commands not, nor obeys”.

In this he’d echo the eleven-year-old Shelley

Who’d frequently sign off his letters,

“Now I end. I am not Your obedient servant,

P. B. Shelley.” Since childhood, his own man –

And a boy who grew up hating excess

Most of all monetary wealth.

A mausoleum now depicts his 29-year-old corpse,

Where his body’s held up by winged lions.

Shelley saw, “Commerce has set the mark of selfishness:

The signet of its all enslaving power”

He also saw that, “War is a kind of superstition;

The pageantry of arms and badges

Corrupts the imagination of men.”

*

Shelley wrote the first atheist tract printed in English,

Scaring Oxford into behaving like a child:

Unable to respond except with the values of bigots

It expelled the rationalist who’d ruffled its feathers.

Oxford agreed with the London ‘Courier’, a Tory paper,

In publishing an obituary of Shelley which began:

“Shelley, the writer of some infidel poetry, has been drowned:

Now he knows whether there is a God or no.”12

But Byron’s verdict would flush away their vicious sneers:

“You were all brutally mistaken about Shelley.

He was the best and least selfish man I knew.”

An atheist who could be the supreme altruist,

And the empathy expressed in Shelley’s lines:

“The fainting Indian on his native Plains

Writhes to superior power’s unnumbered pains”

Prompted Krishnamurti to say, “Shelley is as sacred as the Bible.”

“Ah, did you once see Shelley plain,

And did he stop and speak to you?”13

An awe-struck Robert Browning once asked an old man

Rumored to have met Shelley in his youth.

*

When Shelley was expelled from Oxford

He’d walk from Sussex to Wales;

He’d help reclaim Traeth Mawr marsh in Tremadoc

And defend Luddites, now hanged by the State.

He’d left to escape from “suspicion, coldness and villainy”

(Now taking the shape of Home Office spies)

But in Wales he was refreshed by being “embosomed

In the solitude of Wales’s mountains”

“And woods and rivers – silent, solitary, and old”.

He stayed at Cwm Elan outside Rhayadar

A place “where every beauty seems centred”

Though all of it was destined to be submerged.

For the houses Shelley lived in, Cwm Elan And then Nantgwyllt,

Along with the village of Llanwddyn,

would be swallowed up –

Poisoned by progress and greed.

The River Claerwen was dammed and flooded

So England’s ‘Satanic mills’ could steal its water

Replacing the water capitalism had contaminated

With the deadly dust of industrial progress.

But if poets were “the legislators of the world”

As Shelley, prophetic poet, had wished

The valley’s water would be as pure as it once was

And the beauties of Claerwen be unburied.

An old woman who delivered post to Cwm Elan

Would remember, “He was a very strange gentleman.

He wore a little cap and had his neck bare.

He loved to sail a wooden boat

“About a foot in length, and he’d run along the banks

Of the mountain streams using a pole

To direct his little craft through the rapids,

And keep it from shipwreck on the rocks.”

Shelley sensed an organic unity that pervaded living things

And two centuries before New Age and Gaian thinking

He was painting pictures of ecological harmony:

“Henceforth . . . all plants, / And creeping forms, and insects rainbow-winged, / And birds, and beasts, and fish, and human shapes, / . . . shall take / And interchange sweet nutriment . . . (III, iii).

And then in Prometheus Unbound,

He saw that Love, “In the motion of the very leaves

Of spring in the blue air there is then found

A secret correspondence with our heart.

There is eloquence in the tongue-less wind

And a melody in the flowing of brooks

And the rustling of the reeds beside them

Which by their inconceivable relation

To something within the soul,

Awaken the spirits to a dance

Of breathless rapture, and bring tears

Of mysterious tenderness to the eyes . . .”

Words that indicate a union with Nature,

If not even a worship of Pan;

Shelley pursued images of unifying love,

In an Eden with no angry fathers.

*

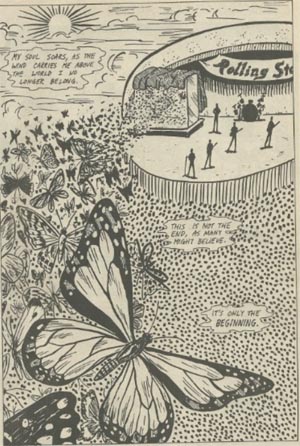

When Brian Jones drowned, only something

By Shelley could answer the case:

‘Adonais’ which Shelley wrote on Keats’ death was read,

And butterflies were released by those left.

Rock n’Roll Commix #6, from “Satisfaction, an Unauthorized Biography: Release the Butterflies”,

Shelley once urged that the wind should “scatter,

As from an unextinguish’d hearth

My words among mankind, like ashes and sparks,”

And, in an age to come, he’d be granted his wish.

In Bob Dylan’s winsome folk melody ‘Blowin’ in the Wind’

The same thought surfaces that Shelley first had,

In his incantation ‘Ode to the West Wind’:

Namely after the Wind’s currents Transform the woods into instruments,

The answers to life can be blown around

like leaves

With each leaf carrying his lyrical thoughts –

And spreading his ideas, and philosophy:

“Be my spirit,” Shelley implores it, “Be thou me!”

And he imagines his messages wafting over the world,

The first answers to be ‘blowing in the wind’

And likewise Shelley’s metaphor from the same poem,

“Drive my dead thoughts across the universe

Like withered leaves to quicken a new birth!”

Would be slipped into a John Lennon song –

One called “Across the Universe” in which Lennon

Has his words blowing about, echoing Shelley’s phrasing:

“Words are flowing out like endless rain into a paper cup

They slither wildly as they slip away across the universe.”

Lennon describes his “thoughts meandering

like a restless wind inside a letter box

They tumble blindly as they make their way across the universe.”

It’s as if Shelley’s invocation “Be thou, spirit fierce, my spirit!

Be thou me, impetuous one!” was persisting two centuries later.

For Lennon’s words that gusted in the same poetic wind,

Were to carry all Shelley’s messages:

Shelley asked “Can Man be free if Woman be a slave ?”

And Lennon wrote, “Women are the slaves of the slaves”;

Shelley’s ringing clarion call: “we are many they are few,/Rise like lions after slumber”

Became Lennon’s call for “Power to the people”.

Shelley said that “The words ‘I’ and ‘you’ And ‘they’ are simply grammatical devices”

And Lennon said “I am he as you are he as you are me and we are all together”

Echoing Shelley word for word.

Shelley said that “Love is the sole law

Which should govern the moral world”14

His words were distilled by John Lennon

Into “All you need is Love”.

Lennon would say of his ‘Across the universe’

“It’s one of the best lyrics I’ve written.

“In fact,” he insisted, “it could be the best”

From across the universe where nothing dies

Shelley might let slip a wry smile.15

In the words of Gregory Corso, the Beat poet,

Known as “an urchin Shelley”

And whom Ginsberg called “the awakener of youth”

“Shelley was a sharp Daddy.”

“The one who really turned me on”, Corso said,

Was Shelley, “not too much his poetry, but his life.

I said, ‘Ah a poet could really have a good life on this planet.’

That fucker was beautiful. A sharp man.”16

*

Shelley made a return visit to Oxford, incognito,

With Thomas Love Peacock and Charles Clairmont,

To show Mary around the town, and to see the rooms

That he’d shared with Jefferson Hogg.

Then, during this visit, which Charles Clairmont described,

Shelley told them of his scientific ideas:

Of his looking through telescopes at the rings of Saturn

And through microscopes at flies’ wings and cheese mites,

At “the vermicular animalculae in vinegar”

At all of the protozoan life-forms

Which they’d both compare to drowning fairies.

Shelley said this was where he’d first wondered

How mankind might “begin the world again.”

“We visited the very rooms,” Clairmont said,

“Where the two noted infidels, Shelley and Hogg,

Pored with the incessant and unwearied application of the alchemist,

Over the certified and natural boundaries of human knowledge.”17

Shelley showed Mary where he’d had rows of galvanic batteries

And told her of his friends’ excitement at their lightning discharges

And how they’d all queue up for electric shocks.

Then he explained his fascination with the story

Of Prometheus who stole fire from the gods

And he suggested that the story could be modernized

If you switched flames for electric sparks.

For at Oxford Shelley would exclaim to Hogg,

“What a mighty instrument would electricity be

In the hands of him who knew how to wield it”.

He then bubbled over with his obsession with balloons:

“What will not an extraordinary combination of troughs of colossal magnitude –

A well arranged system of hundreds of metallic plates – effect?”

And he and Mary became mechanised aeronauts, in their heads.

Then during this return visit Shelley also described

The experiments he’d once conducted

With a man he referred to as the “alchemist in the attic”

A Dr Lind of Windsor in Berkshire.

Shelley referred to this mysterious Dr Lind

By saying, ‘I owe that man far – oh! Far more

“Than I owe my father”.

And Shelley would immortalize Dr Lind

As the character of Zonoras,

The wise old teacher of science and philosophy

In Shelley’s poem, ‘Athanase’.

“Prince Athanase,” he wrote, “had one beloved friend

An old, old man, with hair of silver white

And lips where heavenly smiles would hang and blend

With his wise words; and eyes whose arrowy light

Shone like the reflex of a thousand minds.”

Now Dr Lind was the first man in England to hear

Of the experiments of Dr Galvani,

And Lind would take Shelley under his wing

To repeat Galvani’s ideas with his experiments.

In which they’d pass charges through dead garden frogs

And watch them jump, as it seemed, back to life,

Then Shelley told Mary how very soon afterwards

He had treated his sisters’ chilblains

And cured them with small, electric currents.18

From then on Mary saw Shelley in a new light

And soon she’d find herself tempted

To recreate her husband as a fictional being,

One she’d make larger than life

Thtough drawing on dramatic facts such as the sensation

That she’d felt herself stirred by electric jolts

Coming from the sensual love she shared with Shelley

Which was now giving her a new way of being

And changing her utterly through the belief

That she’d joined her soul with his –

A soul she believed carried such a transformative charge

That she felt they could both conquer death.

Then she’d combine all this with her witnessing

The same man demonized by the world –

Denounced for his having let loose a monster:

An atheistical monster in a Christian state.

A man even accused of usurping his Creator

And a man who was also pilloried

For his nurturing another unwelcome ‘monster’,

Namely England’s huge underclass –

Then exploited by employers and treated

With more contempt than animals,

‘Common labourers’ whom fear and hatred would compare

To a Hydra-headed Caliban.

A monster considered capable of anything A blood-crazed, conscienceless beast;

The working-man was a ‘Monster’ whose hopes Shelley,

Was now misguidedly raising

Through his identifying with their cause.

In their wisdom, the English upper classes

Saw them all as sub-humans it was their duty to suppress

While idealizing themselves as a Herculean race,

With a monarch appointed by God.

A monarch whose task was to seek out such monsters;

Any such bestial insurgents,

Hell-bent on disrupting their privileges

So it was their task to control them:

To identify any dangerous stirrings,

To suppress them for their own good,

To jail the disaffected, to transport them for life,

Even executing children as young as ten.

And while Shelley was spending a small allowance

On schemes of political justice

His empathy with outsiders first made him a class traitor,

And then characterized him as ‘diabolical’.

After this visit to Oxford, a fictional character

Came to Mary almost fully formed.

And when she lost Shelley’s child this creation,

Who aimed to conquer death, took a hold.

“I saw with shut eyes”, Mary would write,

“But acute mental vision—

I saw the pale student of unhallowed arts Kneeling beside the thing he had put together.

“I saw the hideous phantasm of a man stretched out, and

Then, on the working of some powerful engine,

Show signs of life and stir with an uneasy, half-vital motion.”

In this reverie Mary recast her husband as a scientist

With an assembly of paupers’ limbs

That he’d reanimate through flashes of lightning –

Mary saw Shelley as Victor Frankenstein.

Her Frankenstein would draw on aspects of Shelley

In his rebellion against tradition;

In his attempting to give life to those who didn’t have one,

And in his shaping destiny by dispensing with god.

Mary would have her phantom delving into the power of electricity,

A power of equal fascination to Shelley

Who’d see it as an emblematic of the Muse’s spark

That gave man his feelings of divinity. (19)

Just like Shelley, Victor desires “to begin the world again”

To penetrate the secrets of nature

And to find the philosopher’s stone

And the elixir of eternal life.

Like Shelley at Oxford, Victor Frankenstein

Reads Agrippa,

Paracelsus and Albertus Magnus

And just like Shelley, Frankenstein thinks it’s possible

To come back to life from the dead.

Mary describes Frankenstein doing this, much as Shelley had tried,

Reviving corpses through his applying

Doses of bottled-up lightning from galvanic jars –

But through science instead of superstition…

In breathing life into Victor Frankenstein

Mary ventriloquizes Shelley,

And when Frankestein bubbles over with enthusiasm

Mary has him talking in Shelley’s voice:

“So much has been done, exclaimed the soul of Frankenstein—more, far more, will I achieve; treading in the steps already marked, I will pioneer a new way, explore unknown powers, and unfold to the world the deepest mysteries of creation.”

But though Frankenstein was destined to become

Science fiction’s greatest archetype,

Shelley would be setting himself an even greater task

Than just being the model for Mary’s novel.

For Shelley was to set his heart on electrifying

England’s entire body politic:

Bringing it back from the dead with his words –

Words that spelled out revolution.

Though poets of the Victorian establishment

Such as the dour Mathew Arnold,

Dismissed Shelley’s incantations as “Beautiful, but ineffectual”

His thought became dynamite to hardcore activists

He was a guiding light to the Chartists:

“The seed you sow, another reaps;

The wealth you find, another keeps.”

Pirate versions of his ‘Queen Mab’ were circulated

And read aloud at union meetings

Whereupon it was considered so inflammatory

That Moxon, its printer, was jailed.

“Ye who suffer woes untold,” Shelley wrote

Or to feel or to behold

Your lost country bought and sold

With a price of blood and gold.”

And a moribund body politic being jolted

And being given a new lease of life

Through an electrical charge from Shelley’s lines,

Wasn’t limited to England or to his time.

11 “…there is no real wealth but the labour of man. Were the mountains of gold and the valleys of silver, the world would not be one grain of corn the richer, no one comfort would be added to the human race.” (P.B.S. notes on Queen Mab)

12 The Courier, 5 August 1822; the thought, incidentally, of Shelley being an infidel student who had spawned a monster (namely his atheistical ‘outrage’) is believed to have sown a seed in Mary Shelley’s mind, one which grew into her novel about Frankenstein’s disturbing creation for, a few years after his expulsion, Shelley would return to Oxford to show Mary around.. Edward Dowden, in The Life of Percy Bysshe Shelley,2 vols. 1866, I, p. 529, quotes a member of the visiting party, Charles Clairmont: :”We visited the very rooms where the two noted infidels, Shelley and Hogg, […] pored with the incessant and unwearied application of the alchemist, over the certified and natural boundaries of human knowledge.” Richard Holmes was the first to make the suggestion: “Perhaps something Shelley said on this day first laid the germ of an idea in Mary’s mind for a story involving an infidel student, working secretly in the heart of a respectable university, to bring forth a diabolic creation.” Richard Holmes, Shelley: the Pursuit, London: Quartet, 1976, p. 291

13 Robert Browning, Memorabilia, 1855

14 from ‘A Defence of Poetry’

15 In his 1970 interview with Rolling Stone, Lennon referred to the song as perhaps the best, most poetic lyric he ever wrote: “It’s one of the best lyrics I’ve written. In fact, it could be the best. It’s good poetry, or whatever you call it, without chewin’ it. See, the ones I like are the ones that stand as words, without melody. They don’t have to have any melody, like a poem, you can read them.”

16 Corso was described as “an urchin Shelley” by Bruce Cook; interview with Gregory Corso, March 22, Grand Forks, Dakota, USA., Beat Scene, no 66, Autumn, 2011, pp.18-29

17 Edward Dowden, in The Life of Percy Bysshe Shelley, 2 vols. 1866, I, p. 529, quotes a member of the visiting party, Charles Clairmont: ”We visited the very rooms where the two noted infidels, Shelley and Hogg, […] pored with the incessant and unwearied application of the alchemist, over the certified and natural boundaries of human knowledge.”

18 When my brother commenced his studies in chemistry, and practiced electricity upon us, I confess my pleasure in it was entirely negatived by terror at its effects. Whenever he came to me with his piece of folded brown packing-paper under his arm, and a bit of wire and a bottle (if I remember right) my heart would sink with fear at his approach; but shame kept me silent, and, with as many others as he could collect, we were placed hand-in-hand round the nursery table to be electrified; but when a suggestion was made that chilblains were to be cured by this means, my terror overwhelmed all other feelings, and the expression of it released me from all future annoyance’.

Read more: http://wiki.answers.com/Q/How_was_Mary_Shelley_directly_linked_to_Dr_Lind#ixzz1kyZhiA8r

19 Richard Holmes is the first to make the suggestion: “Perhaps something Shelley said on this day first laid the germ of an idea in Mary’s mind for a story involving an infidel student, working secretly in the heart of a respectable university, to bring forth a diabolic creation.” Richard Holmes, Shelley: the Pursuit, London: Quartet, 1976, p. 291

Edward Dowden, in The Life of Percy Bysshe Shelley, 2 vols. 1866, I, p. 529, quotes a member of the visiting party, Charles Clairmont: ”We visited the very rooms where the two noted infidels, Shelley and Hogg, […] pored with the incessant and unwearied application of the alchemist, over the certified and natural boundaries of human knowledge.”

Shelley lives in Heathcote, and Heathcore lives in us.

Comment by Cy Lester on 18 August, 2018 at 1:30 pmHeathcote is our Frankenstein’s Laureate (and don’t deserve no misprint).

Comment by Cy Lester on 18 August, 2018 at 1:40 pm