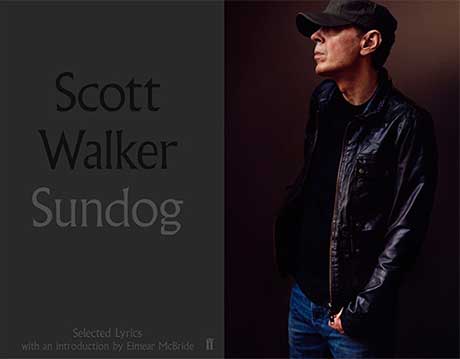

Sundig – Scott Walker

That’s a deliberate misspelling, by the way. The good: Sundog is Scott Walker’s selection of lyrics.

The bad: (an interpretation). Scott famously stated he never revisits his work after it goes to press and it makes me wonder, during his failing health and still busy working life, if he even visited this book at all, after first selecting which songs he wished to be included. Though we are treated to new songs. But the book doesn’t seem to be complied by him. Anyone, in a few hours, could grab and paste his lyrics from a google search and compile a book from them. Unfortunately it looks that way, from the outset as that is all that can account for some howling omissions. This or lack of editorial intervention betrays a pitiful lack of reverence for Scott’s painstaking legacy of work.

First though, you have to wade through the verbose musings of Eimear McBride’s great pains, simply to tell us – in conflated and somewhat patronising terms – how unfathomable and un-poetic it all is, as it supposedly transcends most human comprehension. In her experience, songwriters are not poets and never the twain shall meet, Scott is no exception. Has her immediate success gone to her head and made her dizzy? Just what does she think poetry is? And is this the kind of ‘awareness’ being passed on through emerging literary talents? Something poetic is suddenly not poetry? Not all poets are lyricists, true, but many of Scott’s pop songs were overtly poetic. What a pity we were not treated to an introduction (as if Scott needed one) from someone who actually witnessed first hand the impacting emergence of each of his beautiful works. And what Sundog provides us with is a beautiful legacy laid out as powerful poetry.

Any lover of Scott Walker – as his regular listeners invariably are, from many variations of the term – whether fond of the ‘old’ younger Scott or the newer older Scott, or both, find no problem fathoming what he does for them. For all the acclaimed skill justifiably lavished upon him by musos and sound artists who know what they’re doing, the affection he is held in goes deeper, much deeper and broader than any claimed understanding of the individual himself. Why? Because of the earthly understanding of life held in common. And possibly by not shying away from pain and suffering, finding a place for that amongst the increasingly plasticised denial and positivia of western pop-culture, brings us some acknowledgement and relief, like any chanteur or chanteuse. An acute observer of that is what he is and has always been. Not highfaluting or rooted in elitist Gnosticism. Not esoteric. Not Finnegan’s Wake at all. Earthliness and human vulnerability – coursing in the veins and mucus and sweat and pain and euphoria – is his quality and his stock-in-trade. He knows his craft and sculpts it for us in admirable form.

The ugly: Above all, Scott Walker recognised and validated sympathy, empathy and personal weaknesses contrasted by surrounding ignorance, judgment and violent imposition. Pathos was his key and his humour. All of this is distinctly earthy and does not depart even when he gets into the psyche’ with his latter works. Deeply poetic and not unfathomable but acutely tapping into the spirit, how words and music and sounds provoke and resound within us, reflecting our discord and misgivings. He recognised the buttons to push and nailed them, while avoiding the self-satisfying security of superficial interpretation and intellectualising. He wanted to get us out of this mental and audible stupor, while saying – ‘look, you’re familiar with this sound’ or at least some unfortunate people are. Listen to the musicality of a goat or mule, it places us where he wants us to be. It’s not like we’ve never been to such a place, or encountered it in some form. It might not be where we’d choose to hire a bus to go on our jolly holidays.

We’re not all incapable of discernment, even when it is subliminal, as if we have to be ‘patient’ with his later work, so as not to pull a face from Tilt onwards and lazily have to say – “ooh what’s this?” An acquired taste, of course! It’s rightly something not experienced much in commercial music, but none of it is entirely new. It exists in various forms through musical history, in classical and operatic form and Ennio Morricone. Scott’s recent work on film scores and his nod to various classical refrains all follow something of convention. His time signatures and even how he breaks them convey recognisable conventions, though placed in unconventional settings. Even the slapping of a hide with a wooden plank, or a jovial refrain on flute, or a choking sensation. There’s also cheekiness which pierces beyond uncompromising brutality, reflecting baser instincts behind the act experienced in sadistic treatment; like how some German gas chamber operators pitted prisoners violently against one another, for a joke, promising reward of life for the victor – before exterminating them. You can shiver at this or disagree, but the mirror Scott led us to peer into wasn’t for plastering over warts with foundation. It celebrates the wonder of people, how minds relate seemingly unconnected things, through fear, exposure, stream of consciousness, dream, imagination, deflection, or stretched beyond our usual frames of reference. These things are real, not abstract. He is saying this is us, what we are made up of. Some things not governed by comprehension. It is a sense of mourning and regret, how appalling we can all be. And what do we expect?

Maybe it was Scott’s characteristic dissatisfaction with how to convey emotion musically that drove him beyond what we accept as conventional – but the most obscure process, sound, lyric, dissonance, intimate ‘accident’ reinforces not his abandonment of human feeling but its existentialism. You get the sense, when he avoids his characteristic vibrato, in some later vocal passages, that he wants to get closer to what we call the inhumanity in some treatment meted out to victims, just as done to animals. The animalistic or ‘inhuman’ within us or the effect of making us so. As if he wants us to acknowledge and accept how we continue to abuse and condone abuse and turn our ears from it, the horror weak or empowered beings are capable of. But this in no way alters Walker’s feeling of empathy, it is not unsympathetic. Far from taking a trip around the universe, it is a deeply honest peering into the murkiness of soul. It is characteristically Walker exploring how individuality can possibly survive the things causing the cauterisation of heart and mind, or come to express it. Like how do you survive a desert, or torture? What are its constituents?

McBride, searching for a cool line, states his late work (that dominates the book) “does not speak of danger but feels like it.” True, but Walker wasn’t seeking sensationalism for the sake of it, like some tabloid journalist of sound-manipulation, trying to drag us backwards into a black room. It would only be that to the predictable and cliché, so pronouncing it that does no one, including him, any favours. He knew which vibrations could beautifully and profoundly disturb and used them with instinctive measure, as he felt them before us, knowing this would be conveyed to us. Instinctively human. So I reject some of McBride’s over-precious assessment of it being exalted art and I can’t see Scott Walker accepting that, if he had any dealings with this book.

Scott Walker has rung, memorably, in the ears and hearts of many people who feel his music and him through it. This is what music is pre-eminently about and Walker never deviated from that. He is graspable, guttural, sublime and most of all as vulnerable as we all are. He wanted us to access this, I think to save ourselves some pain or at least recognise ourselves. This is why we regard him, not as stranger but fatherly, or a friend, or lover, and an intuitive consummate composer. Artist yes, unconventional yes, but to try label him as indefinable or at best avant-garde, I think misses HIS point entirely.

Revisiting his work to send us his chosen lyrics in one volume, with a few personal insights, is now as precious as a farewell letter, though sadly not even dictated, it appears, from the artsy-fartsy line spacing and graphics fiddling – words separated line by line, when they are not in the songs, to pad it out. “The Luzerner Zeitung” wobbles all over the page twice in altering fonts and sizes, as if we need reminding of how unusually he sings it, yet the editor isn’t so pedantic to recall it’s actually sung three times. One chorus crosses the spine of the book in-ter-up-ted-with-hy-phen-a-tion-mak-ing-it-har-der-to-r-e-a-d and louder passages are CAPITALISED in (upper-)case our memories are going as well as our hearing and sight. All of this contrasts the austere appearance of the cover sleeve, which is simple and tactile and comforting around the featureless pitch black hardback. But that in itself exhibits the vulnerability and humour inherent in tragedy Scott probably smirks at, with his arm around Brel’s shoulder as they observe his funeral together over a glass of Dago Red.

We mourn the passing of this sensualist, sad that his individuality will no longer thrill us with new discoveries. But we cannot help but celebrate him for enriching our experience of our own lives and the lives and life surrounding us. You don’t have to listen to and like Scott Walker. He never needed us to. But his work has intent and that intent is to empathise, enrich and explore. For that and doing it in such a sensitive resonant way, those of us who love him feel we owe him the greatest regard and unceasing affection. I suspect this last work will become a fond, treasured, well-thumbed volume for fellow bath-time crooners who wish to disturb the neighbours. Thank goodness he left us this last touch in time.

Scott Engel’s gift to us as a relatively (for idolised people) unknown individual is invaluable and leaves a gaping but richly satisfying hole. If he was a musical egg, his shell would be Faberge, spectacular but with crackled, flaking fragile enamel, and the hole would be the endless echoing interior his songs rebound from and constantly caress within, with his stunning poetry and whispers.

And didn’t you know? He was not the world’s strongest man.

Kendal Eaton.

Thank you, Kendal. When I heard the news of Scott Walker’s death, I cried. It felt as if my oldest friend had died. The man had substance, style, integrity and genuine creative originality. My accomplice on so many dark nights, in and out of company: part of the fabric of my life. I’ll miss him.

Comment by Dafydd ap Pedr on 21 April, 2019 at 10:05 amWalker Bros

Godot not Godo

songwriters not poets?

Comment by jeff cloves on 21 April, 2019 at 3:35 pmKendal Eaton

has none of this

and from me too

no no no

bravo

fado

Godo

I once saw

The Walker BRos

in Schmidt’s Restaurant

(long gone)

in old Fitzrovia

they were at the height

of their fame

and appeared like

earthly angels and Engels

everyone stopped eating

and looked at them

the sun ain’t gonna

shine anymore?

of course it is