Decades: Brian Eno in the 1970s, Gary Parsons (127pp, £15.99, Sonicbond)

Gary Parsons has written a highly condensed summary of Brian Eno’s music from the 1970s, mixing together facts, anecdotes, critical opinion and hearsay in an engaging and highly readable manner. There’s also a snazzy full colour photo section. However, the book could benefit from a final edit, as there are some awkward phrases and several places where the same information is repeated across two sections of writing. I’d like to have seen more acknowledgement of sources too, and a bibliography would also have been useful.

The focus of the book is Eno’s solo and collaborative work, but the book starts with the formation of Roxy Music and the band’s first album. For Your Pleasure, their wonderful second album, is considered alongside Fripp & Eno’s (No Pussyfooting), an album of tape loops and treated guitar, before we get to Eno’s solo albums proper. Although released under Eno’s name, 1974’s Here Come the Warm Jets and Taking Tiger Mountain By Strategy are both collaborative albums, with Eno in the role of circus master and sonic magician, carefully adding and subtracting recordings by his musical friends and acquaintances in the studio to build up dense, rhythmic pop songs, which drew on doo-wop, glam rock and the avant-garde to spectacular effect.

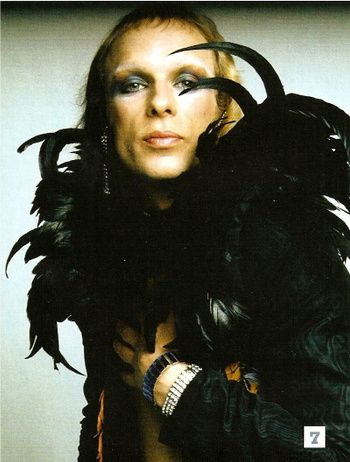

It’s hard to realise how shocking Roxy Music, and particularly Brian Eno’s androgynous dressing-up, was at the time, and also how much of a star he was. Much of the reason for Eno’s exit from Roxy Music was the fact that the press focussed on and wanted to interview Eno rather than Bryan Ferry. Eno would use his fame and attention to gain the release of further experimental albums: Discreet Music, which paired an evolving sound loop with three deconstructions of a canon by Johann Pachelbel; and Evening Star, a continuation of his work with Robert Fripp. 1975 also saw the release of Another Green World, Eno’s third solo album, another work mostly put together in the studio. Although remembered as one of his song albums, it is actually mostly instrumental; and despite much (often retrospective) critical acclaim, it remains one of my least favourite Eno works: I find it cold and over-spacious, despite some rip-roaring guitar passages and haunting fragments of song.

Parsons chooses this point in the book for an ‘Intermission’, to consider ‘Eno As Producer And Session Player’, offering a whirlwind tour of projects Eno guested on or produced, including a brief summary of the Obscure Label which Eno curated and persuaded Island Records to release. I can’t help feeling that Parsons has missed a couple of tricks here. Eno’s involvement with Talking Heads seems a pivotal moment for the band, Eno himself, and perhaps New York new wave (or post-punk) itself. Talking Heads’ use of recording strategies, and influence of found and world-music material on their Fear of Music album (and even more so on the later Remain In Light) led to a major repositioning and eventual re-imagining of the band, which had a huge knock-on influence and effect on music at the time. In a similar way, one can see the ten Obscure Label albums as a summary of Eno’s influences and contacts at the time; nearly all of his systems, strategies and ideas are informed and signposted by the work of composers such as John Cage, Harold Budd, Michael Nyman and Gavin Bryars; musicians such as David Toop, Max Eastley and Jan Steele; and artists like his friend Tom Phillips.

1976 saw Eno continue his enthusiastic engagement with new music. He packaged up some instrumentals as Music for Films in the hope of selling to advertisers and filmmakers (a highly successful idea), worked with Harmonia on music that would eventually be released as Harmonia & Eno ’76: Tracks And Traces, and played live with Phil Manzanera’s band/project 801, which was documented on the 801 Live album. Then it was into 1977, and Berlin, with Eno invited by David Bowie to produce, contribute to and generally interfere with the making of what would become Low and Heroes (which is actually called “Heroes”), two of Bowie’s finest works. Eno also worked with Cluster to make Cluster & Eno, and finally completed Before And After Science, the fourth (and best) of his 70s’ solo albums, which had been a struggle to make, probably because Eno was already busy thinking ahead and planning to move on.

Eno’s specialism seemed, indeed still seems, to be the ability to rationalise procedures and processes into systems, strategies and simple ideas, clearly (if occasionally somewhat pretentiously). Discreet Music, along with Harold Budd’s and John Cage’s work, helped Eno ‘invent’ or at least conceptualise ambient music; playing games in the recording studio allowed Eno and the artist Peter Schmidt to produce 1974’s first edition of Oblique Strategies, a boxed set of cards with instructions or aphorisms on for the reader to respond to. Eno and Bowie would use these in Berlin, Eno would later use them with the likes of U2, and many others (including myself) continue to use them and similar works by other writers and artists to this day. In a somewhat self-derogatory way, Eno has spoken of how he has moved towards composition which requires the least work from him for the most output. Initially influenced by Steve Reich’s recordings of tape recorders slowly going out of sync with each other, Eno has gone on to set up musical and visual art systems or programmes that will not produce identical juxtapositions of sound or image for years on end, an intriguing combination of both simplicity and complexity. There is a clarity of purpose and thought here, which allows Eno time to focus on other interests and ideas.

But back to the 70s, to 1979, which Parsons calls ‘The Year of Distraction’. Although only giving full attention to the Eno, Moebius and Roedelius album After The Heat, Parsons also discusses Eno’s disappointing work with Devo, the No Wave compilation he curated, a collaboration with Snatch (Judy Nylon and Patti Palladin) and his move to New York, as well as Bowie’s live presentation of Low and ‘Heroes’ on the ISOLAR 2 tour, recorded for posterity on the Stage album. Parson quotes at length from a contemporaneous Zigzag magazine interview with Eno, where he expresses a desire to do ‘some things where I keep further back from being the focal point of what’s happening, where I take a much more subsidary role.’ This sense of doubt or possible retreat is echoed later on in another quote, this time from the Daily Press, where Eno notes that he ‘is in the interesting position of being neither a good producer nor a good musician’, adding that ‘[a]nything complicated I do is done by ingenuity rather than skill’.

But perhaps ingenuity is a skill? I think so. Whilst Eno and Bowie worked less harmoniously together this time round, and Parsons is not totally convinced by Bowie’s Lodger album from 1979, claiming that Bowie was keen to move on to new projects, it’s interesting that Bowie’s next album, Scary Monsters and Super Creeps, would feature a certain Mr Fripp, flown in to let rip with his guitar on (or over) a number of tracks. 1979 is also the year Eno released Music for Airports, one of his definitive ambient albums; recorded with Harold Budd and Jon Hassell; and applied his ambient sound ideas to video, releasing two collections of slow-moving, colour adjusted visual recordings, one of Manhattan, the other of a female body. And then Eno flew to California and out of the decade under consideration in this book.

But there’s more! Parsons ends with ‘Afterword: Eno In The Eighties And Beyond’, which looks ahead to suggest that ‘[t]he eighties would come to define what Eno is for the rest of his career’ but also writes that ‘[f]or many of his fans, his seventies output is still seen as his high water-mark musically, where he seemed to be constantly ahead of the curve’, and that ‘[t]he seventies were Brian Eno helped to change the course of rock music forever’. He’s not wrong, but I suspect Eno would be more interested in the effect he had on non-rock music through his work in the visual arts, his writing and lectures, his interests in ambient and world music, his consideration of the studio as an instrument, the use of collaboration and generative systems, and through his support for work by War Child, The Long Now, Stop the War Coalition and several human rights organisations. Parsons, however, is not so keen on some of Eno’s more recent music, noting that many albums repeat ideas, which ‘might seem like, an element of stasis in Eno’s work’. I’m sure, however, that Eno will be relieved that Parsons is of the opinion that ‘after 50 years as a recording artist I think this can be allowed.’ Well that’s alright then.

Rupert Loydell