Ted Burke Introduction and Interview by Malcolm Paul

It’s been a real pleasure working on this interview with Ted Burke, American born poet, musician and photographer, and now I’m pleased to say it will be published by International Times.

Too often in my opinion on both sides of the Atlantic, the spotlight of recognition and appreciation shines on just a few of the same poets, writers and artists – past and present – and misses out on many other deserving artists, who should be read, listened to and enjoyed with equal enthusiasm.

I mean the counterculture Celebs don’t always have the best lines.

And quite honestly who reads On the Road, Howl, Coney Island of The Mind more than once or a couple of times at most in their lives?

When it comes to the American Beats and their UK equivalents – though anything other than the Transatlantic bonding – literary partnership rarely gets a mention.

I’ve been reading poetry since early childhood and before I could read, my mother read it to me – so in a way I was almost destined to be a writer/poet – my interest transcends that of just a journalistic write-up.

What I wanted to do from an early age was to read the Greats, the Classics and the Innovators, the Modernists, the Surrealists and The New Realists as well as A Alvarez Confessional Poets.

Just as Ted Burke did, I wanted to move on and dig deeper, to find the new poets, especially those who didn’t always get the limelight and perhaps existed in the world of the small press/ chat books. They were often the poets reading their own works aloud in bars/bookstores and basements, just about any venue that would shelter the willing listener with a hunger for something new, exciting and unordained. Writers as deserving of the recognition and success as many of the A list names. Writers like Ted Burke and many others inadequately acknowledged – out there waiting to be shared.

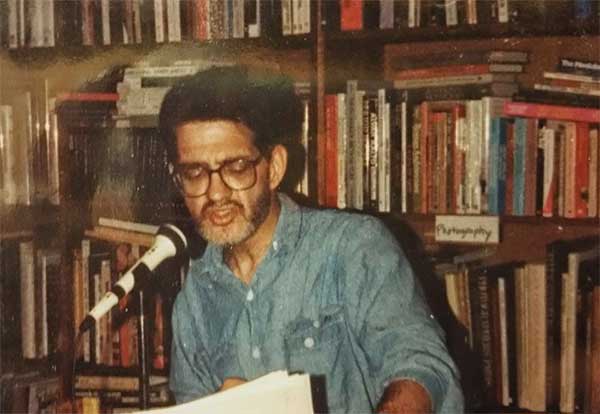

Ted was born in Detroit, Michigan. A city I won’t compete with Ted in describing. Later on, for family reasons Ted moved to San Diego, California – where now retired, he runs a book shop, plays Blues harmonica in Clubs – most notably San Diego’s Troubadour Club – writes loads of poetry and never passes up on an opportunity to take photographs of people and places around him. What I sometimes refer to as Beat photography.

Ted is a multi talented artist who deserves a place along with many other poets in the Parthenon of artists, who bring the City and its people, their (micro and macro) relationships to life.

Writing in their own inimitable way using like Ted a craft they are gently honing to perfection. Writing such memorable lines as:

The day starts

with a bum taking a leak

against a full trash can.

It already smelled bad,

so I guess he’d

thought no one

would notice a little more

stink on the street.

(from The Way This Day Went)

Beauty and Love

talk over lunch

in such a way

that their image

suddenly blurs

in front of your eyes

and the movement to swat

a pestering fly

looks like hands on a ship railings waving

“adieu” and “goodbye.’’

(from Problem of Disguise)

Ted’s poetry is as sharp as a ‘paper cut’ and as socially critical as a Ben Shahn’s painting. After all, it was Ban Shahn, who said “I paint two things: what I love and what I abhor.” With Ted, it’s poetry at its best. Read on.

**********

Burke’s Questions: Ted if this was a live interview, I would probably ask you to play us in with a tune on your harmonica. If you picked a tune, which one would it be and why?

I’d most likely play Cannonball Adderley’s blues tune The Work Song, which I learned from listening continuously , obsessively to the Paul Butterfield Butterfield Blues Band’s second album East West. It was the first song I learned all the way through, and it was the one that me hipped to the idea of chord changes, those items that make a solo listenable. I still have fun playing it. I’d seen the original Butterfield Band in Detroit at the Chessmate, a no age limit folk club in 1966. Tour acts like Chuck and Joni Mitchell, Tom Rush, Phil Ochs , even the Blues Magoos would stop there while on tour. Cramped space, no alcohol, just coffee and soft drinks, and a five dollar admission. The hardest part was saving up five dollars and convincing by parents to let me go . I was sixteen at the time and Detroit was a hard town after the sun went down. Not that it was a day at the beach during the daytime either.

Ted you have many different interests in the field of the Arts:

Poetry, Music, Journalism, Photography and Bookstore.

(If I’ve missed any apologies).

Would you mind if we talked about them in a form of sequence? Is that possible?

Though my feeling is that you don’t compartmentalise your arts and interests in life.

All those listed have perhaps a place in your creative story or journey – more a ‘oneness’, ‘fusion’ – rather than, say, picking an art like a ‘tool’ from a box as required by a separate genre and putting it to work.

Am I right in thinking this?

Yes, I think you’re on to something. I might have already mentioned that I have a forty percent loss of hearing since birth and have always felt that the world was largely hidden from me. Even at ages eight, nine, through the teens and into adulthood, it felt like my experience of the world was incomplete. I was quiet much of the time, observing how people spoke to one another—the expressions on their faces, hand gestures, their postures. I read a lot from the beginning, first when my mother read stories to me and I could hear her words clearly, and then when I was able to read books on my own. It was like visiting a land where I knew exactly what was discussed, what the situation was, what actions meant. As with many who are severely hard of hearing, I had a speech impediment, and while in early grade school I was put in what was called “speech class,” where I was taught how to speak up, enunciate words, and articulate vowels.

I was obsessed with the sounds of words as I heard them in my head; I associated language with music and, in time, equated the selection of words in my poetry and prose with, say, a jazz improviser choosing which notes to play in a complex run of extemporized musical phrases. That sounds terribly pretentious, and I can imagine readers thinking this California fellow is another sun-baked poseur, but this is about as well as I can describe my “creative process.” Absent an oblique aesthetic philosophy to fit myself into, whatever I do as a poet is an attempt to complete the other half of the worldly experience I felt was withheld due to my hearing loss. Back in the day, I tried to fake my way through conversations by acting as if I understood what was said or asked, and often gave answers that baffled, confused, or amused those I was talking to.

There’s an old joke where one hard-of-hearing fellow tells a friend that he has a new hearing aid.

“How’s it working?” asks the friend, to which the other fellow says, “Just great.” The friend then asks, “What kind is it?”

“Four o’clock,” says the man with the new hearing aid.

That’s an old Norm Crosby joke that characterizes how I navigated my younger days—faking my way through encounters, sometimes getting away with it, sometimes responding with non sequiturs when my bluffs failed. Kids will be kids, and many thought I was an idiot. I came to believe it myself. My poems were, in some way, talking back to the world, making use of the verbal miscues I created, and becoming very aware of the sounds of words and phrases and what puns or other odd turns of logic could produce. My project, to use that dreadful word, was to write poems that sounded as if they should be coherent statements but which jumped from one stanza’s idea to another in a shift that would surprise me but sounded “right.” I like to think that my best writing has the logic of finely improvised jazz or blues; there are articulable notions in the work, I believe, but how well they work on the page can’t be separated from how well they work on the ear. The euphony, the rhythm, the sound of the words as they flow is no less important to getting across the nuances. Nuance is a word I dislike, almost as much as I dislike the term “subtext,” but I guess either gets across what’s in the poems that’s not immediately apparent. The poet sometimes does things that are very interesting, even cool, without knowing it. Some poets, I should say. I’m vain enough to think I do that sometimes.

Could you say a bit about how that process works in regard to your life and art?

For example, do you carry a camera around with you at all times?

Yes, but that’s a given since I have my smart phone on me a majority of the time. The pictures might look better, more polished, more defined if I used a quality camera, but the photos are from my phone’s camera and I’ve become used to using it and tweaking the photos to a variety of tweaks with editing applications both on the phone and on my PC.

Pen and paper? (I guess young poets use a smartphone to record ideas for poems now.)

Never. The image of a poet musing, dreamy-eyed under a tree or in a café, scratching their chin with pen in hand as they think of their next brilliant bit of word salad, is the stuff of cringe. I tend to go through whatever needs to be done during the day—pay bills, see friends, go to work, shop, do laundry, all the banal things that make our lives predictable—and wait until it’s time to write, in front of the keyboard and monitor, to reflect, recollect, and collate the mundane routines as they occurred, in odd instances with people, places, things, remarks, various confusions, and misunderstandings from the last few days. This means being open to whatever occurs to me while trying to write stanzas that would logically or tonally seem to follow one another. These ideas might be recent events in the news, a piece of music I remember because it fits thematically into the premise of a poem, or a memory from childhood or more recent times. It’s a fragile approach to writing, I guess, but for me, brandishing a pen and notebook out in the world every time I think of something I’m vain enough to believe is clever or worth remembering misses the mark; it takes me out of the world I’m supposed to be a part of, negotiating the deluge of life that cannot be bracketed. So I write, or compose poems later, maybe days later, attempting to bring the memory together in some kind of order, in an expression that essentially is the practice of not getting it right. Images, similes, metaphors, allegories of any sort can’t contain the reality each poem tries to deal with, but they can, I think, beautifully express a person’s response to a flow of phenomena that will not reveal its reasons for being.

Is your harmonica tucked in your back pocket, ready for the next opportunity to join in a session?

I always have a harmonica, or at least 90 percent of the time. I feel incomplete if I don’t have one on me, ready to be played as an opportunity presents itself.

I’d like to ask you if you could tell our readers a little bit about your life, family, education, career and lifelong involvement in the Arts?

Born in Detroit Michigan, now living in San Diego California?

Can you tell us a bit about that journey?

Born and raised in Detroit, home of Motown, home of the MC5 and The Stooges, automobile capital of the world, lots of factories, lots of working class, lots of very beautiful architecture, lots of very pissed off people. My parents were both interior designers and ran a successful business of their own there, which is where, I guess, I picked up an interest in art and the knack and need to express myself in ways other than tantrums and swear words. Being hard of hearing, already mentioned, I read lots of books and became interested in some way in “the life of the mind”, whatever that happened to be. I got into a lot of fights , but that was ok because I had early exposure to black music of all sorts and even developed an interest in free jazz a la Coltrane and Sun Ra, who played in concert with The MC5 and the Ambouy Dukes on the same bill. Local promoters tended to be more eclectic in how they booked, lots of different styles and musicians booked for the same engagement. My father had a very bad case of asthma and the severe changes of season in Michigan were doing him great harm. My parents were thinking of moving to either California or Arizona for a more stable climate for my Dad. The riots of 1967 , the worst in American history at the time, hastened their decision to relocate the family to the West Coast. Dad nearly accepted a job in Scottsdale Arizona, but my Mom basically made him turn that job down and to have us land in San Diego, California instead.

I would really love to know when and how you got started with your writing?

Back in the mid-sixties, I was just another Catholic kid at a junior high in Detroit, soaking up every scrap of pop, rock, and soul from the AM radio static. When Dylan’s “Like a Rolling Stone” first cut through the noise, that was it for me—I couldn’t shake the feeling that he was onto something honest and raw, with lyrics that twisted like alleyways and an attitude sharp as broken glass. I didn’t know the first thing about poetry, really, but I started scrawling my own odd, adolescent verses in spiral notebooks, trying to catch whatever fire he had in his voice. Sometimes I stumble on those old attempts, and it’s painful—so young, so clueless, but stubborn as hell. I got knocked around on playgrounds and tried to sound wise in front of college kids spouting Frost and Marcuse and Williams. Awkward times for an awkward kid, but I stuck with it.

The best thing that came out of that early Dylan obsession was my curiosity: who was he reading? I cared less about his musical heroes, more about the books stacked around him—Ginsberg, Burroughs, Eliot, Rimbaud. I tracked those writers down, devoured them, and followed the thread from one to another, stuffing my head with biographies and criticism, even the sorts that made my eyes cross. That journey landed me as a literature major at UC San Diego, with a brief detour into grad school at SDSU. While I bounced around as a music reviewer—a fancy name for someone paid to scribble about records—my real writing was always poems, hundreds of them, quick as lightning. I once bragged at a grad party that I was the fastest poet in Southern California, and a faculty member shot back, “Does quality over quantity matter these days?” Tough crowd. Most of my early work was a tangle of words—blame Ashbery and O’Hara—but somewhere in that mess, a real voice started to surface, one that sounded a little more like me and a little less like everyone else.

The English author Geoff Nicholson said in an interview last year:

”the author isn’t always the best judge of his own influences”.

Would you agree?

For a while, I believed my poetry was entirely original—sometimes arrogantly so. After getting sober in 1987, I reflected on my work and realised the influence of poets like T.S. Eliot, Bob Dylan, Marianne Moore, Frank O’Hara, Amiri Baraka, and Ferlinghetti. Their styles shaped my writing from then on.

Do you get comments about your poetry that makes you think: ‘Oh, I didn’t see that in my work. That’s interesting’?

Certainly, and sometimes, those comments land with the soft, surprising weight of a dropped apple in the grass. In the seventies, there was this fellow in San Diego—David Banks—who gathered poets in his bungalow on India Street, his living room gently lit with the gold of late afternoon and the dust of a hundred unrecorded verses. He’d urge each of us to our feet, nudging our words from the page into the fragile air, reminding us that the poem’s true form only flickered into life when it was spoken, and when the listening room—stirring, attentive—joined in the act of creation.

David, already a bit frayed at the edges by the time I met him, believed a poem was not so much finished as released, like a kite cut from its string, left to the interpretations of the breezes. That notion has always pleased me—this idea that the poet is more midwife than parent, and that the poem itself is a kind of fugitive, always escaping the boundaries we thought we’d drawn for it.

There’s a certain electricity, I find, in hearing readers react to my poems, especially when their insights send a current of recognition through me: yes, that’s what was there, all along, even if I hadn’t named it myself. The city-bound poets I admire—those who braid together a snatch of film dialogue, a faded billboard, a philosophical aside, all planted in the cracked sidewalk of daily life—helped me see that poetry’s surface can be as ordinary as a diner window, and its depths as hidden as the stars above a sodium-lit street. So, yes, other people’s readings can be revelations. Sometimes, I look back at a poem through their lens and discover, with something like awe, that their vision was always coiled inside my words, waiting to unwind. I don’t wish to sound rapturous, but those are moments when the act of writing feels, for a brief beat, nearly holy.

There is usually a symbiotic relationship between one’s early reading and the direction of the coming of age writer.

Could you talk a bit about your early reading and how it influenced your own writing?

Early reading? My first forays were into The Waste Land by Eliot, after getting lost in a hefty Bob Dylan songbook loaded with the lyrics of his greatest songs—this was the late Sixties, when Dylan’s mystique loomed large. I was obsessed: I read everything about Dylan I could find, and repeatedly came across his praise for Eliot and Rimbaud as guiding lights for his surrealist style. Curious, I picked up Eliot and swiftly fell under his spell. He taught me that it was perfectly acceptable for a reader to feel a poem “doesn’t make sense,” as long as some emotional truth or poetic intention shone through the confusion. It’s a delicate balance—vague and elusive—but for me, it meant that a poet with an ear for rhythm and euphony could create palpable feelings: despair, spiritual longing, and that sense of loss as the modern age recedes further from the so-called golden eras of human achievement, until those times are merely faded rumours. The shift in how I thought about poetry happened quickly. Not long before discovering Dylan, Eliot, the Beats and other writers, I had been a devoted fan of Rod McKuen. I owned several albums of him reading his poetry—sentimental and stylised, built on the persona of a sensitive soul wandering the city, standing on misty piers, listening to fog horns echoing through the night. It was corny, unabashedly commercial, yet when I was sixteen or seventeen, it spoke to me; it made me yearn for experiences of my own so I could put them into words. Of course, that led to clumsy attempts to imitate McKuen—a naïve boy shadowing a mediocre scribe. Still, I have to credit him as an influence, since his verse was what first got me writing.

Were you influenced by the Beats?

Ginsberg’s work—especially “Howl,” “America,” and those sprawling, incantatory poems—shaped me profoundly. His lines captured the unsettled terror of being an artist in the shadow of the atomic bomb and the paranoia stalking the era: communism, intellectuals, gay artists, straight artists, smart women, civil rights. The biblical rhythms and sweeping imagery—shimmering skyscrapers, cold stretches of despair—taught me that poetry could be an endless revelation, each new sentence unfolding fresh meaning. In my twenties, I wrote several awkward Ginsberg imitations: a handful of promising lines amid a jumble of petulant attempts at wild brilliance. Those drafts followed me from apartment to apartment for years, until one day in the late 1980s I stood by a dumpster and watched the garbage truck haul away boxes of my old poetry and prose. I knew I’d never revisit that material, and from then on, I started composing on a word processor—learning to write in a new way.

Kerouac, on the other hand, never resonated with me. I found his writing more an exercise in reckless improvisation than true genius, as if he were trying to channel the brilliance of Charlie Parker or Coltrane by simply flooding his work with adjectives, verbs, and similes. I read “On the Road” as a kind of generational rite of passage, more to understand its cultural significance than out of admiration. Before I dismissed him in conversation or print, I made sure to read him—so I knew where I stood.

Recently I discussed with Simon Warner how important the ‘crossover’ was between the Beats and the 1960s counterculture.

I think if you are a writer of a certain age, you would have found it hard not to have travelled from one cultural movement to another.

Post Second World War culture couldn’t have developed artistically without the Beats in my opinion. Certainly when it came to writing.

In Europe the Surrealists would be a big influence, as well as the ‘poete maudit‘ Rimbaud – Baudelaire – Mallarmé – Nerval.

(Definitely my influences)

Did you read these poets as a young writer?

Did they influence you?

They influenced me secondarily, after I realized the wonders of Eliot, Wallace Stevens and William Carlos Williams, Dylan and the elite generation of “rock poets” like Joni Mitchell, Paul Simon, Leonard Cohen, Phil Ochs. I read the French Symbolists closely while studying literature at the University of California, San Diego, especially Rimbaud and Verlaine, it would be better to say that I was more influenced by the writers who greatly influenced by the Continental modernists, those American and British writers who were older than I was at the time.

Though Beats were an American phenomenon – it did jump ship in Liverpool and gave us the Mersey Poets – Brian Patten, Adrian Henri and Roger McGough. I had the pleasure of interviewing Brian Patten last year about his part in the Beats transatlantic crossing and the Liverpool scene.

Brian joked about Allen Ginsberg visiting Liverpool and commenting that it was “the centre of human consciousness”.

Brian’s take on that – smiling – was “he probably said that about Milwaukee”

Was San Diego ever “at the present moment, the center of consciousness of the human universe”?

While San Diego is deeply familiar to me—a landscape woven with memories and distinct neighbourhoods—I never saw it as the centre of the universe. It’s true the city boasts an impressive theatre scene and excels in the arts, education, and medical science, all hallmarks of a vibrant metropolis. Yet, for much of its history, San Diego felt more like an expansive suburb of Los Angeles than a cultural capital in its own right. Thankfully, that perception has shifted over time, as the city has cultivated its own unique identity and creative energy.

Ted, would you agree that the Beat Movement had the potential to be not only Transatlantic, but international as well?

It seems to me that the Beat style was inherently transatlantic, drawing inspiration not only from the American landscape but also from Eastern philosophies—most notably Zen Buddhism. The idea of “be here now,” of embracing the present and experiencing each moment without the filter of ego, resonated deeply with a generation of writers in the 1950s, shaped as they were by the aftermath of two world wars. As the American middle class rose and the Eisenhower era ushered in an emphasis on comfort, convenience, and material accumulation, many sensed an encroaching conformity and spiritual stagnation—a threat not only to individual expression, but to creativity itself.

In this climate, Eastern spirituality offered the Beat writers a transformative lens. Yet, as often happens when concepts travel across cultures, those ideas were reinterpreted, reshaped, and fused with the American penchant for rugged individualism. In that way, Beat writing became an international blend—a unique convergence of East and West, tradition and rebellion, spiritual searching and individual assertion.

Especially for novelists and poets?

Though I feel that the Beats could equally inspire a painter, a photographer (The Japanese master Daido Moriyama ‘On the Road’ on photography), and most definitely musicians and poets such as Bob Dylan, Patti Smith and Tom Waits – to name but three.

As I found out last year when I researched the works of Germany’s excellent poets and novelists – Rolf Dieter Brinkmann and Jorg Fauser, there is an international connection.

Both authors were very much influenced by the American Beats.

Sadly they both died tragically young in separate road accidents, but left a lasting legacy of great poetic works and faction memoirs: ‘Raw Material‘ and ‘Snowman’ (Jorg Fauser).

Sadly too few of their works have been translated into English.

Fortunately both authors are lucky to have an excellent translator in the hands of your fellow American, the poet and translator Mark Terrilll, who has done an excellent job of bringing their work to us in English.

Also worth reading is Niall Griffiths excellent English language introduction to Jorg Fauser’s aforementioned novel ‘Raw Material’.

Did you come from a home where you were exposed to the Arts from an early age? Books? Music? Painting?

My parents were both interior designers in Detroit and later in San Diego, so I was brought around things that had aesthetic value. They often brought home expensive statuettes, finely crafted and one of a kind wall hangings, exotic pieces of furniture. My mother was a reader and read to me when I was very young. I was on her lap as she read, something I loved because I was born with a significant hearing loss, which still pesters me to this day. I could hear her read clearly, I took in the sounds of the words and marvelled at how rich and nuanced they sounded, something like music.

In the Libby Larsen article, it’s mentioned in:

‘MY FATHER INTERCEPTS MY TRIP TO ANOTHER PLANET’.

“The 16ths begin to mellow as Burke writes, “back in time for Flintstones…” and soon we return to our unbound existence, as the boy opens his eyes to discover his father carrying him off to bed. Larsen quotes the Cole Porter song, I Love Paris as Burke describes his father singing the song’s words as he drifts off to sleep. The piano cadences on what feels very much like a dominant chord as Larsen re-employs her D pedal tones, while the Cole Porter melody seems to find its tonal center in G major.”

Might that suggest that your father had a musical background?

My father enjoyed singing show tunes, especially after a couple of after-work cocktails. He would belt out “I Love Paris” and really ham it up—usually before dinner and sometimes afterward. But no, I don’t recall him having a musical background. Our house was always filled with books, music, and art as my four siblings and I grew up. I suppose that’s where my creative inclinations came from. I originally aspired to be a visual artist—a comic book artist, in fact—and I even wrote and illustrated my own comic strips for a while. Eventually, my interests shifted to writing after I fell in love with the James Bond novels and, later, with science fiction and fantasy. My brother Owen went on to become a world-class jazz drummer in the Louie Bellson style, as well as a brilliant visual artist and instrument maker.

In general terms (outside of the family) how would you describe music playing around you as you grew up in either Detroit or San Diego?

Music was the most important thing in Detroit when I lived there. Music of all kinds, the city had everything going on musically even though it was on the decline as a major city. There was a rich history of jazz and blues artists from decades before I was born, there was Motown records, which took over the world it seemed, and there were the local rock bands . The MC5, the Stooges, Ambouy Dukes, Bob Seger and the Last Heard, The Rationals, SRC, The Frost, Savage Rose, Wilson Mower Pursuit. Luckily Detroit had a number of no age limit music clubs, or clubs that featured no age limit shows some nights of the week, and it was fairly easy to get rides to shows with friends who could borrow their parents cars. Detroit had the Grande Ballroom run by a hip capitalist named Uncle Russ and he brought Cream, Jethro Tull, Led Zep, Jefferson Airplane, Grateful Dead , Pink Floyd to the city and booked local bands to open for them. Half the time you went to see the local supporting band and gave only half an ear to whoever was headlining.

Were you a MC5s fan by any chance? 1968.

Yes, a huge MC5 fan , and a fan of the Stooges, Bob Seger and the Last Heard, The Rationals, a whole slew of Detroit bands that made Detroit a hot bed of proto-punk rock. I saw the MC5 about five times before I moved to California in 1969. They remain the most exciting band I’ve ever seen in my 73 years of life. And I’ve been to many concerts over many years as a music journalist. The MC5 set a high bar.

“According to Kramer, MC5 of this period was politically influenced by the Marxism of the Black Panther Party and Fred Hampton, and poets of the Beat Generation such as Allen Ginsberg and Ed Sanders, or Modernist poets like Charles Olson. Black Panther Party founder Huey P.Newton prompted John Sinclair to found the White Panthers, a militant leftist organization of white people working to assist the Black Panthers. Shortly after, Sinclair was arrested for possession of marijuana.”

So there was a lot of heavy political interconnectedness.

Had you left Detroit by then?

My family moved from Detroit to San Diego in the summer of 1969, a two week drive across the country.

In the UK we tend to think of California as being almost a separate country within the United States i.e. politically, socially and culturally (or should that be counter-culturally?), especially cities like San Francisco.

Do you feel happier to be in California now?

Well, I suppose so, since it’s the home where , at the age of 73, most of my monumental life’s experiences have happened. I’ve been the happiest in California and the most profoundly depressed and it’s where the lay of the land, the ocean, the mountains that ring the city, the houses and apartments I’ve lived , all inhabit a central part of my nervous system; I have what you might call a physical reaction of a kind when an element of a terrain I’ve known intimately for decades turns up missing, like buildings, shops, street names, entire neighbourhoods cleared out to make way for freeways, ersatz modernist condominium developments, or high rise office buildings that will lay empty for decades, if not forever

Do you think your poetry has changed significantly over the years and in what way?

I suppose my poetry has changed—like the kitchen light flicking on at midnight, illuminating only what’s immediately present. The lines have grown leaner, less draped in brocade, more like a single chair in a quiet room. I’ve learned, over the years, there’s no need to wear a “poet’s voice” like an old borrowed coat. Sometimes, an image is enough: a saltshaker, a window left open in spring, standing there with its small confidence. It’s a relief, really, to let the words arrive as themselves, unburdened by the heavy ornaments of language, and to trust, at last, the simple precision of seeing things as they are—even if the world outside keeps rearranging the furniture when I’m not looking.

You have been prolific over the years. Do you still find there is as much enthusiasm for poetry as there used to be in the world of writing?

It seems that poetry’s popularity ebbs and flows with the tides of fashion. Occasionally, a poet rises to prominence, gathers a substantial following, and brings renewed attention to the art form. Yet, as trends shift, broad enthusiasm for poetry often recedes, leaving a core group of dedicated readers. There is certainly no lack of poets—if anything, there may be more than ever, though not all stand out in a meaningful way. This has always been true. Yesterday, critics praised Billy Collins; today, Rupi Kaur captures the world’s imagination. Who will be read fifty years from now—assuming we have another half-century and that literacy endures—is anyone’s guess.

As a poet like you, I miss the ‘small press’ and the opportunities it gave up and coming poets to get started.

Do you still have in the US an active small local press functioning?

Have you managed to collect most of your poetry into one anthology yet?

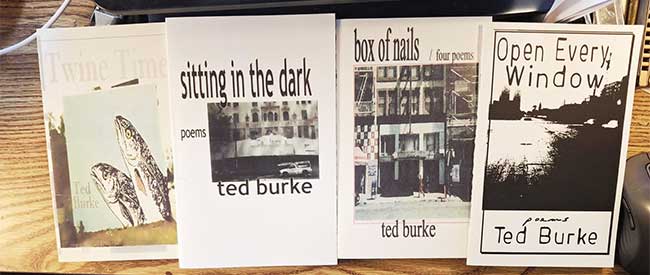

That’s an ongoing project I want to complete soon. Anyone who’s interested can dial up a blog I set up for many of my poems, https://ted-burke-poems.blogspot.com/. Several chapbooks are available for download as FlipHTML5 files, Readers can sign up for a free account and read them on the site or download them for later.

Ted, having read the three chat books you sent me last year – ‘Problems Of Disguise‘, ‘Open Every Window ‘, ‘Sitting In The Dark‘, I would like to perhaps make a few comments, and ask a few questions if you don’t mind.

I find your visions of the cities and towns to be like a collage of images. I would go as far as to suggest ‘cut ups’. I’m thinking here William Burroughs/Brion Gysin!

(A form of poetry known as Cut-out, Remix, or Découpé in French, involves the poet cutting up and rearranging a source text.)

Do we have the scissors in our head?

People sometimes ask me what drugs I took when I wrote particular poems. Alas, I took none. I inhabit my poetic mind as an urban Imagist—sometimes surreal, often cryptic, always relishing the gleefully expressive non sequitur. I believe I follow a logic when I align phrases, choose odd usages, and introduce unexpected turns that don’t seem to “logically” fit together. I treat prose as the photograph and poetry as the x-ray. But I strive to avoid incoherence, unreadability, or didacticism. I constantly think in musical terms, mostly imagining each stanza as part of the spontaneous compositions you hear in Wayne Shorter’s improvisations—another attempt to do my best resolutely in the moment, elaborating on themes from previous stanzas. I relate each stanza to the others as I develop an idea, introduce an unexpected notion inspired by earlier images, and expand or condense a set of expressed ideas over several sections, aiming to resolve everything in an atmosphere, tonality, or feeling you wouldn’t expect to reach.

“For this piece I want to be inspired by our own language, our own rhythms and the way we (our culture) use ordinary, every-person objects (like a cigarette, a radio, a cardboard box you find in your garage…) to transport us into our interior selves where we articulate emotions that are universal.”

Libby Larsen.

Ted, check out the art of the Swiss Artist Dieter Roth sometime.

I think you would find it interesting.

In your poetry – layers of urban life – drenched in smoke and mist – gas fumes – toxicity, charged up with an often unseen energy source resound.

As if there were generators in the alleys and the throbbing of machinery following you as you walked or drove around the metropolis, thoughts like coins jammed in slots escaping reason.

A sort of cross between William Blake’s ‘Satanic Mills‘, the world of Raymond Carver’s ‘Short Cuts’ and the lowlife haunts of Nelson Algren.

With the people stepping out of Edward Hopper paintings. Gershwin’s music. Aaron Copeland ‘Music For A Great City’. People observing – swapping trinkets of conversation, before turning up the collars on their heavy overcoats and heading home in need of warmth and shelter, hoping to be safe.

Is the urban environment so important to your writing?

Are your people overwhelmed by the town/city and the claustrophobia it grips them with? How easy would it be to find love? Negotiate friendship? Think of something higher? Would a transcendence be thinkable, let alone possible?

I have to admit that when I read your urban ‘city poems‘ I was reminded of the poetry of Poland’s greatest poet Zbigniew Herbert, and especially his poem ‘The Monster of Mister Cogito‘.

The Monster Of Mr Cogito

Lucky Saint George

from his knight’s saddle

could exactly evaluate

the strength and movements of the dragon

the first principle of strategy

is to assess the enemy accurately

Mr Cogito

is in a worse position

he sits in the low

saddle of a valley

covered with thick fog

through fog it is impossible to perceive

fiery eyes

greedy claws

jaws

through fog

one sees only

the shimmering of nothingness

the monster of Mr Cogito

has no measurements

it is difficult to describe

escapes definition

it is like an immense depression

spread out over the country

it can’t be pierced

with a pen

with an argument

or spear

were it not for its suffocating weight

and the death it sends down

one would think

it is the hallucination

of a sick imagination

but it exists

for certain it exists

like carbon monoxide it fills

houses temples markets

poisons wells

destroys the structures of the mind

covers bread with mould

the proof of the existence of the monster

is its victims

it is not direct proof

but sufficient

reasonable people say

we can live together

with the monster

we only have to avoid

sudden movements

sudden speech

if there is a threat assume

the form of a rock or a leaf

listen to wise Nature

recommending mimicry

that we breathe shallowly

pretend we aren’t there

Mr Cogito however

does not want a life of make-believe

he would like to fight

with the monster

on firm ground

so he walks out at dawn

into a sleepy suburb

carefully equipped

with a long sharp object

he calls to the monster

on the empty streets

he offends the monster

provokes the monster

like a bold skirmisher

of an army that doesn’t exist

he calls –

come out contemptible coward

through the fog

one sees only

the huge snout of nothingness

Mr Cogito wants to enter

the uneven battle

it ought to happen

possibly soon

before there is

a fall from inertia

an ordinary death without glory

suffocation from formlessness

You would definitely be in good company.

Writing poetry to Zbigniew Herbert was no different to gasping for breath.

Poetry as ‘oxygen’.

In the same way it was for his contemporary Tadeusz Rozewicz.

words (2004)

words have been used up

chewed up like chewing gum

by lovely young mouths

and turned into a white

bubble

weakened by politicians

they serve to whiten

teeth

to cleanse the oral

cavity

when I was a child

a word

could heal wounds

could be given

to a loved one

now weakened

wrapped in newspaper words

still poison still stink

still inflict wounds

hidden in heads

hidden in hearts

hidden under dresses

of young women

hidden in holy books

they explode

and kill

Your poem ‘A Dozen Blackbirds’ is a remarkable poem. One of many I fell in love with, reading through your chat books.

‘Problem of Disguise‘, ‘Stammering Through Paradise’, ‘Rexall’,‘The Way This Day Went‘ (love it).

‘Machine Head’ is such an excellent poem too, Ted – I can see why you/Libby felt it could marry with music as well as it did.

We can talk about the collaboration with Libby Larsen later.

Though I have visited America many times it still feels like such an American scenery. Unfamiliar to a Brit.

A place where life and drama seems to be squeezed out of a tube as if they were a scripted toothpaste snake. I look forward to seeing your poetry in publications I know, which would make you welcome, like International Times.

Music Journalism:

In your years as a music journalist, did you ever feel like switching to any other forms of writing i.e. novels or plays? Your cover biography alludes to a ‘book’?

Did you write one? (You may have done so)

Did you ever feel tempted to switch written genres? Lots of writers – mostly novelists – say that poetry is a step on the first rung of the ladder to become a full-time writer.

(I’m thinking Susan Hill)

With perhaps a short stop off in the pit-stop of the short stories genre. Any thoughts on that one?

It could be argued nobody earns a living as a poet anymore.

Could we ever stop?

As the great Fernando Pessoa wrote:

“The poet is a man who feigns/And feigns so thoroughly, at last/He manages to feign as pain/The pain he really feels,” wrote Pessoa under his own name, “And thus, around its jolting track/There runs, to keep our reason busy,/The circling clockwork train of ours/That men agree to call a heart.”

As Andre Gide also said to a student who said he was considering stopping writing – “you mean you can and you don’t?”

Could you ever envisage giving up writing Ted?

I don’t think of it too often. I sometimes have thoughts of losing my sight , my hearing in full, senses essential to the kind of writing I try to do. But I hope I don’t stop writing for any reason any time soon, since it’s the one process, the one art that allows me to change my mind about things in the world on the basis of new evidence.

Do you love playing the Blues?

The blues is the basis for all good art in the 20th century.

Which are your favourite Blues artists? Playing on the harmonica – or any other instruments.

Too many to name, but there are those who’ve inspired me on the harmonica. Honestly, I’ve been influenced by more guitarists than harp players. BB King, Freddie King, Albert King, Johnny Winter, Harvey Mandel, Little Milton, Magic Sam, Howlin Wolf. But for harmonica players, its Paul Butterfield, Charlie Musselwhite, Little Walter, Charlie McCoy, Sonny Boy Williams, Sonny Terry, Sugar Blue.

Do modern bands use harmonica anymore?

If they use harmonica, it’s used as texture, not as an actual part of the band membership. The J.Geils Band with Magic Dick or War featuring Lee Oskar, real bands that had wide popularity, seem a thing of the past.

Or is it just the diehard Blues and R&B Rock bands that use a harmonica?

I’d rather listen to the Stones in the early years playing harmonica on Blues covers, than the later pure hard rock music albums.

You talk about in one of your poems, I paraphrase “the melancholy sound of the harmonica playing the Blues”.

Would you describe yourself as being a ’melancholic person’? I’m not a doctor, I can’t say people are ‘Depressed’.

I get depressed sometimes and might have a clinical predisposition to feeling low down, which ought not surprise me or anyone else considering that I was in my cups until 1987, the year I sobered up .

Melancholia is common amongst poets.

I would agree, as it seems to be the case that poets in their best years as writers have amazingly acute long-term memories and remember the sensations they felt while dramatic/traumatic events occurred to them in their younger lives. When I do that kind of mental cave diving, it’s not unusual for the old emotions to stir up and for the body to reproduce the physical sensations that attend a sudden death in the family, falling in love , getting fired or beaten up. The good thing about not dying so soon and still having a desire to write, means you can take a longer view and think about past events and one’s changing sense of life’s meaning , if any, in the writing.

Do we self medicate with verses and stanza on the back of envelopes and beer mats?

I appreciate what Harold Bloom said about literature in an interview. He dismissed the claims of other intellectuals that literature improves the human race or provides us with moralities and philosophies that have practical utility. He called those notions nonsense, and argued that the true value and power of literature, especially in the work of strong poets, lies in how it helps us reflect on ourselves. We, as humans, are deeply introspective, prone to self-doubt and rage. Reading poetry provides context and framework—a way to see ourselves not as isolated agents in a vacuum, but as part of the world, with agency, talents, and the ability to create reasons to continue living. Through creative commitment, we can withstand banality, doubt, and ceaseless self-recrimination, and make something that helps us process the astonishing and often daunting fact that we exist for only a brief time, and that our so-called gift of life came without any instructions.

How does the void of a blank sheet of paper make you feel?

One of the great terrors of my life is the tyranny of the blank page. I see a page with no writing, and I am suddenly filled with the dread of having to fill it up with words, sentences, paragraphs that mean something. It’s the fear of failure every time, the fear that one has run out of things to say.

Or do we anaesthetise ourselves with drugs and booze?

“Trip in the wet garage”?

Did you ever travel that road of excess – then turn back?

I went down that road, yeah, and turned back, but just barely. I think I’m incredibly lucky to have found a lot of support in my several efforts to get free of the thing that was killing me. Thinking like Blake’s ”roads of excess leading to paradise“, is romantic and offers a pleasant reassurance to those who are still drinking and using drugs addictively, but they in fact lead only to a black dead end. The road to excess leads to an ugly and early death of the one who sought more sublime kinds of knowledge through drugs and hootch. Drug use and binging on booze as indications that the subject is somehow more attuned with a quality of being that is superior to the rest of the world is one of the greatest lies the generations Post WW2 told themselves and sold to the rest of the world. Jazz guitarist Joe Pass was asked if shooting heroin made him more in the moment, more inspired as an improvisor, and his reply, I recall, was blunt: it only made you think you were playing better. I suspect him listening to solos he recorded while under the sway of smack.

Could you say a bit about your time as a music journalist. Which years were they?

Most active would be between 1973 through the 1980s, for different local arts and music publications, those being The San Diego Reader, San Diego Door, Good Times, The Daily Guardian (UCSD), Revolt in Style. I started a music blog in the late eighties , in the internet’s steampunk days, which turned into a blog where I wrote about anything that got my interest, which was and remains literature, poetry, music, movies, architecture. I aspired to be a cultural critic of a sort; I had lots of opinions and a vocabulary to express them with. I currently write for the San Diego Troubadour, a very fine journal dedicated to the local area music creators . The editor, a sweetheart of a friend named Liz Abbott, gives me license to write about artists, albums and issues I care about.

What type of music did you cover?

A broad range of things, mostly hard rock and experimental rock and pop at the beginning, later shifting my interests to fusion and later concentrating on straight ahead jazz, with an avid interest in avant garde improvisation. Sun Ra, Anthony Braxton, Cecil Taylor, Ornette Coleman.

Did you always get the type of gig you wanted to cover?

Any particular heroes? Lester Bangs? Chistigau? Grail Marcus?

Lester Bangs was a huge influence early on me, I mimicked him, tried to get his tone, humor, sarcasm, and doing all that was important in finding my own way with the words I wanted to deploy on a subject. Christgau was a tad more analytical than Bangs was and was, I think, the best rock critic available when he wrote longer reviews and essays. Few were as sharp and insightful as he could be when I hunkered down for some serious thinking. Marcus is at times a beautiful prose stylist and likely the most knowledgeable of the three (and perhaps smarter than all his peers at the time) , but his writing is often vaguely sketched out, with transitions from subject to subject on matters thinly linked to whatever grand idea he’s trying to get across. He wants the historical overviews he composes to be poetic in effect; he wants to be a combination of James Burke and Ken Burns, putting forth a grand mosaic of items , incidents and issues that surround whoever he’s talking about. It’s a method that’s worked rather well—his book Lipstick Traces is a masterpiece of a kind—but his refusal to present a thesis, a straightforward statement of what he’s going to talk about, is infuriating.

Or were the aforementioned writers in an earlier period?

In the music press during the 60s/70s in the UK – I suspect the USA as well, music journalists lived and worked a ‘Rock and Roll’ lifestyle not dissimilar to some of the musicians and artists they wrote about or interviewed.

Did you witness that, or were in any way part of that?

Did you get to meet any of the musicians you admired, or felt an affinity with?

Do you think Ted that the role of the music press has changed over the years – say from the heyday of the ‘Rolling Stone‘ era? Possibly eroded by the advent of social media and online publishing. Any stories would be interesting.

Record reviews still exist and when I can I read what the views of the critics are in Pitchfork, Rolling Stone, and Spin. But in terms of having any influence on what consumers buy or any power to help a worthy talent earn a living from their art, I think that’s pretty much gone.

Would you consider yourself ‘spiritual‘ in any way?

Spiritual? Perhaps. Art seems largely a search for something lost, something that’s missing, and perhaps it’s a spiritual experience when what you’ve made, whether poem, painting, novel, sculpture results in something the creator didn’t expect, that maybe they’ve gotten closer to that lost and nameless essence, the feeling that they’re on the right path so far. It gets said sometimes that it’s about the journey, not the destination.

I look for it in your poetry, but it feels like it’s something you keep very much to yourself. Do you think I’m being fair?

There’s a story behind the poems, yes, but sometimes I’m not sure what the story is. I almost think that writing poems, the initial composition, is like talking in your sleep. It’s odd combinations of memory,associations, ideas coming out in a flow that at least sound like they make sense even if they don’t literally. I believe that the real art of writing a poem , or at least half the art, comes in the revision, the editing, the rewording. My poetry would be along the lines of Henry James’ idea of novels as “loose, baggy monsters”. Different genre, but the analogy works for poems I read, or at least my poems. I could, when all is done and I set the pen down, break down the stanzas related to one another and give away the significance of the last few lines, but that cheats the reader. I make the maybe arrogant assumption that my writing is clear enough in its phrasing that an interested reader can create their own “meaning”.

Ted, let’s talk photography.

In the Jorg Fauser review I wrote:

“The closest friend the Beat poet has is the ‘street photographer’ Winogrand, Meier and Frank, whose snapshots are like the lines of the Beats poems.

We get the city in a grainy image and the people of the city float by like ghosts, bleached disconnected selves, unwired, the living dead!

Trailing behind them the discarded bunting/ dross of love and what passes for meaning of life in day to day existence.

“If your pictures aren’t good enough, you’re not close enough.” – Robert Capa..

“A photograph is a secret about a secret. The more it tells you, the less you know.” – Diane Arbus

“Photography is painting with light.” – Anonymous

“In street photography, there’s no hiding. You’re out in the middle of the action and have to rely on your own judgement, ability, and courage as a photographer to make a meaningful photograph.” – Alex Webb

Jorg’s photo poem takes a snap of love. But because in the earlier days of photography, you had to have the sun at your back, so it is with love staring down in the lines of Jorg’s poetry. No time for Monet shades or Ansel’s mogadon landscape prints or Dutch masters.

Love naked pegged to a dark room drying line.

Lines/photo negatives from Jorg Fauser.

“When we split up

We stayed in the same place.”

“And soon we lay in each others arms again

and called it love poem”

“But no poem explains to us

the fear of love “.

The Beat poem/photograph?

Ted, do you see a connection between the way you write poems and how you take photographs? Is it about surrendering to the image? Catching an image in flight?

I once wrote as a teen that “all art is guessing”. I still think that’s true.

Is photography a new addition to your arts?

Poetry and photography are about perception, for me. Something I see in the streets, a series of things I see on a walk over time inspires a set of poems, nearly always. I am of the idea that my best shots are of things that are already perfectly arranged, composed, an arrangement of things—trash can, streetlight, woman holding child while window shopping–

Music Collaboration:

Ted, how did your collaboration with Libby Larsen come about?

Libby is very much an established musician and composer, with an extensive background in most forms of music – especially the classics. (Though I see her influences’ range from Witold Lutoslawski to Chuck Berry’.)

Libby came into the bookshop in 2019, I believe. I didn’t know who she was at the time, but when she was checking out I noticed that she was purchasing about hundred dollars in poetry, so I chatted her up a bit, complimented her on her choices. We talked about poetry and inspiration, the muse, all bullet points on the creative process and she asked if I was a poet. I said yes, blushingly I think, and after she purchased the books, I gave her three of my chapbooks which were on hand. It was a wonderful experience I didn’t think much about until she came back a day later with a hand written letter of introduction, telling who she was, an established composer, with a brief of who she’s done commissions for, the organizations she’s a member of, her website, the names of some of the better known pieces she’s composed for orchestras and the like. The letter was a formal request for permission to use four of the poems in a song cycle she’d been commissioned by a world class baritone singer named Will Liverman. I said yes, of course, and through the next couple of years we communicated by email and once by Zoom , mostly to let me know the progress she was making with the three of the four pieces she selected. The long and short of it was that the trilogy of art songs, titled “Machine Head: Ted Burke Poems”, had their world premiere at the 2022 Aspen , Colorado Music Festival. It was a wonderfully moving experience, Mr. Liverman performed my words with the kind of gusto that could wake angels and devils alike. The songs were released in 2024 on a double disc CD called “ Show Me The Way”, in which Mr. Liverman and pianist Jonathan King performed compositions by women composers. It’s a gas knowing I was part of that very fine project.

Thank you Ted.

Hope you enjoyed your questions.

It was a joy researching them.

.

Malcolm Paul

.

Really enjoyed reading this – thanks

A couple of things I’d mention – ‘A Dozen Blackbirds’ could also be a nod to Wallace Stevens (Thirteen Ways of Looking at a Blackbird); street poetry should certainly reference the Objectivists; the global reach of the Beats includes their interest in more Easterly religions

While we tend not to reread novels (you mention On The Road) too often I think we do return to poems (Coney Island of the Mind) much more frequently

Again, thanks

Comment by Steven Taylor on 21 September, 2025 at 9:06 amHi Steven,

Comment by Ted Burke on 21 September, 2025 at 4:07 pmSo glad you enjoyed the read. Yes, “A Dozen Blackbirds” is a nod to Wallace Stevens. Stevens is a hero of mine. You can read my version of the blackbirds at this address: https://www.ted-burke.com/search/label/A%20DOZEN%20BLACKBIRDS