1

The insanity of Economists[i] and the destructive lunacy of Capitalism and Neoliberalism weigh heavily on the minds of those with any sense. The danger of such poisonous human constructs crystallised still further for me when I lodged above a wholefood shop in 1978 for a couple of weeks[ii]. I was 15, my school days were over and several of the shop’s hopeful worker-owners were passionate members of Friends of the Earth. Hard to believe as it may be now, in the light of the impending death knell for Britain of Android Führerin Thatcher, there was still, at least at grass roots level, a great deal of optimism then – the last aerial tendrils trying to brush-off a global insecticide . . .

True, our attempts in 1977 to get the National Union of School Students[iii] off the ground at our school had collapsed. True, the WSL[iv] had failed to make any inroads into Southcourt council estate despite all our door to door efforts at selling Socialist Press . . . several times we got chased down the street as “Fucking commies!” – probably by citizens soon misguidedly to help elect their own long-term nemesis (though at least a few must have got a cheap council house to flog, out of their Satanic bargain).

But, away from the town, out in the country where before long I lived, abandoning art college to decamp to the rural community of Redfields[v] in North Bucks, optimism would continue to seethe or contentedly go to seed. In our minds we could paper over the cracks. In a way, at so many levels – social and political, personal and psychological – this is what we must all maintain the ability to do. Until we come to a crack too wide.

The probability that we have only 12 years left in which to restrict the rate at which we destroy our planet[vi] does not surprise me, nor that the world is now completely off track. Scientists say that this window of opportunity just about remains open[vii], others that 12 years is absurdly optimistic – 3 is nearer the truth. But are enough of us listening?

Since the distant days of North Bucks, I’ve lived in sixteen areas of Britain and though I’ve visited just about every major city, have only ever lived long-term in one. My viewpoint is therefore predominantly rural. Every time I go into a city, my journey is always from isolation. Accustomed to emptiness, the crowded currents of towns and cities – viewed almost with the eye of an extra-terrestrial observer – can interest me intensely. Regardless that they often reek of terminal despair, an experiment gone disastrously wrong, their novelty is such that they can appear to me in a quasi-visionary way: for moments I breathe their idealism – or the idealism of a few people resisting the general current.

2

Leeds was the first city I was fortunate to visit in 2019. A visit I’d been wanting to repeat ever since my fleeting ramble of 2017[viii].

From the platforms of Ribblehead, just south of the famous viaduct, shortly after New Year’s Day, a surprisingly crowded train drew us away. But for the odd grit bin and a few modern signs, it could have been a grey day in January 1919 rather than 2019. Restored and beautifully maintained, the station, has convincingly retreated in time. Down from the high spine of Blea Moor – whose bleakness has always been a fullness to me – we dropped towards the dales of Settle and Hellifield.

Winning the race with traffic on the parallel roads beyond Skipton, our children, eating raw carrots, perked up as station signs appeared from grey fogs less freezing than at Ribblehead . . . marginally.

Canals and lock gates were their other obsession and they were well rewarded through the fascinating post-industrialisation of Keighley, Bingley and Shipley.

Finally, the scale of urbanisation was escalated and multiplied by Leeds. Vast towers whose lights and heating no-doubt burn all night – the last reckless torches of human folly – flank the north side of the tracks converging on Leeds City Station, reputedly the busiest in the north of England. Partly built on arches over the river Aire, combining two previous stations, it was completely rebuilt in 1967 and revamped again between 1999 and 2002.

With a family railcard our fare was less than the cost of road fuel. Perhaps that’s why trains are often over-crowded? If railways should be replacing road and certainly air travel, new coaching stock needs to be built now. There’s little hope of cutting transport carbon emissions otherwise.

Signing a pledge not to fly back in 1993, neither my wife nor I have ever been tempted by the absurd under-pricing of air travel – another of those delusions of economics. The idea of expanding airports in a time of climate emergency, is a hideous anachronism[ix]. Just for starters, I would discontinue all domestic flights tomorrow: which would be no more than a minor starting point to accepting that if we want to survive at all, living standards must fall – something the unemployed and disadvantaged majorities, even in this country, have been on the sharp end of for years. Something which after the foot-stamping, self-destructive, pique of Brexit, we may have to become accustomed to.

Perhaps the imaginative counter to closing airports would be to nostalgically return to the trash TV and spy films of the past, which worshipped the ‘freedom’ of air travel we now so thoughtlessly take for granted. If you watch enough of these, it’s easy to believe that you’ve flown all over Europe – at such a low level that you can almost touch the Colosseum or the Eiffel Tower, the domes of Red Square or the Statue of Liberty, the Brandenburg Gate, the Pyramids, or Rio’s Christ the Redeemer. We need to use our imagination rather than our credit cards – or in my case, that old chipped piggy-bank – to paper over the cracks.

3

At the inaugural meeting of our local Extinction Rebellion group (or XR[x] – a rapidly growing national organisation preparing for increasing actions of non-violent civil disobedience) in Kendal last month, several contributors drew on the example of the Second World War, suggesting that the situation now is of equal seriousness. The inspirational (if sometimes vague and single-minded[xi]) document sent to members, also makes crystal clear the need for drastic, immediate action by our government. This is our last chance. This is an emergency. But who would trust our current band of self-serving retards with emergency powers? Hence XR’s perhaps optimistic demand for “A national Citizen’s Assembly to oversee the changes, as part of creating a democracy fit for the purpose.”

Looking back to the Second World War and the albeit Conservative-led, coalition government of the time, it was later revealed that some of their extreme measures were maintained merely as propaganda: many of those sawn-off railings for example, were never processed, but dumped out of sight.[xii] Yet ideas like the Squander Bug[xiii] (who in our so-called reality has been feasting himself stupid since the late 1950’s) or Is Your Journey Really Necessary[xiv] remain pertinent. As with at least half the people in any car or on any plane, train or boat, our journey to Leeds wasn’t really necessary. So many things we assume our right in life will have to go.

As my parents and grandparents lived through the Second World War and the following austerity years, they all took a dim view of any kind of waste. They were never happy with the consumerism which later took over. Fortunately, I inherited their principles. A blackbird couldn’t survive on the food we waste each week. Nothing is thrown away. A habit which needs to be replicated throughout the West – whose wastage of food is unacceptable, as is our wastage of energy, of setting thermostats way too high, of driving to the shops at the slightest excuse. In winter we should be wearing jumpers indoors – in most of our houses, we needed a coat and hat! That was once the point of the seasons – to notice the difference. Now, it seems we’ve cracked the global mechanism.

Without wishing to seem preachy or nagging, we need to use less power; and as with airports, the answer regarding congested roads is to control car use, not build more roads. It would be better to have regular, universal, power cuts, than to end up with no power infrastructure at all. That all new-build houses should be built with solar panels is obvious, and there are many such ideas to consider once their flaws and loop-holes are ironed out. The flaws with nuclear power were clear to me at 13 back in the 1970’s – at which time, presumably, all its diehard devotees switched their brains off? Even barring accidents, the insidious toxic legacy of nuclear energy should have made the idea a non-starter. No matter how thirsty you were, would you drink sea-water? If there’s a vast shortfall in the energy we can produce using proper renewables, we just have to manage without it. That is the fact which must be grasped!

Since I was a teenager I’ve been deeply attached to the principles of anarchism: anarchism of the thoughtful, democratic variety. But this does rely heavily on selflessness and generosity, gentleness and self-discipline. Extinction Rebellion clearly appreciates such principles – and that self-sacrifice begins at home. I wonder how many of the things we have which aren’t really necessary, we can give up while we still have a choice?

“We are lemmings pouring towards the drop, so obsessed with seizing the moment that we’re stuck in it, careless of past or future.”

“Unless we can suddenly grow up.”

“You think the human race has stalled at the rash impressionable teenager phase?”[xv]

“Could be – and it’s unlikely to get a chance to age . . .”

4

Turning left out of Leeds station, the children were thrilled to see one of the “biggest Christmas trees in the world” in the City Square. We headed north up Park Row towards the Library and Art Gallery in Victoria Square. These two institutions are cheerfully intermingled without borders or checkpoints and have a wonderfully non-corporate atmosphere, as if we had stumbled into some long-lost workers co-op, or anarcho-socialist Utopia, staffed by bohemians and individualists – all of them helpful, inclusive and friendly. There was also an extraordinary cafe in a tiled hall – but at this stage, as I still had a flask and not much ready cash, I knew a visit was not really necessary.

Depressingly, despite being a painter myself, I rarely find much of the art in galleries memorable. I came across a nice Gertler, an interesting Sutherland and a couple of minor paintings by Jack B Yeats. Strangely enough, given all my assaults on ‘Gimmick Art’ over the years, the first work that caught my attention was Mark Wallinger’s almost accidentally significant installation: Threshold to the Kingdom.[xvi] This covertly shot film shows international passengers arriving at London’s City Airport. Yet even if 70% of Threshold to the Kingdom’s haunting gravitas derives from Gregorio Allegri’s, Miserere mei, Deus[xvii] and another 25% from the process of slowed motion, it does, inadvertently, produce a whole that is greater than the sum of its parts. To quote the background information: “the video appears to have a double meaning: arrival at the United Kingdom, but also at the kingdom of heaven, with a border guard playing the role of St. Peter.”

Perhaps like a great deal of cut-and-paste reflexive ‘art’ common in so many fields today and proliferating like healthy bombsite flowers on the post-modernist ruin of the internet, Wallinger’s could-have-been-jotted-on-the-back-of-an-envelope concept, is extremely fortunate to find in its combination of borrowed power, something so comparatively worthwhile. I even sat through it twice.

Such inspiring serendipities are not something one can connect to many Turner Prize winners – infamous for the detritus of their often industrial-scale aspirations, their knack of producing less than the sum of their concepts: a kind of eternal negative equity!

From the putrefaction encouraged since the Greed is Good faith of the 1980’s, the mould spores giving rise to much Gimmick Art as well as the Turner Prize, arguably puffs up from the cynical manipulations of rich, private collectors: experts at the ‘art’ of the self-fulfilling investment. Others less arrogant are quickly infected. Anxious to be in the swim, public art-buying bodies too, have aped the dismal perceptions of these shallow trend-setters – unfortunately, there are several obvious examples at Leeds . . . but in active counterbalance to such mistakes, in a corridor of the library upstairs, hang the Leeds Tapestries.[xviii]

Taking the meaninglessness of ‘market value’ as an indicator of quality, has no doubt helped us down the road of self-satisfied relativism – on which blind eyes only flick open in response to noisy controversy. Capable of being as destructively consumptive as the sick capitalist society which gave it birth, Gimmick Art blares like a bent trombone – an ultimate exemplar of consumerism (and one which can make its perpetrators rich beyond the right of anyone to be). Not always though. Occasionally, it effectively serves some socially observant, ecological or political purpose. In which case I’m prepared to remove the Gimmick epithet.

5

Whether the perception is quite fair (and despite the authenticity of the artist from whom it spins its name), the Turner Prize has largely come to be seen as a catalogue of joke artists whose inconsequentiality and arbitrariness has – and there’s no doubt about this part – seriously helped derail the always-threatened heart and soul of art. This spirit or at least its creative root – largely resistant to hypocrisy, to decorative and material values, fashion, style or hype – may be happy in the home, or in the internal satisfaction of the outsider, the hobbyist, or the amateur art lover, but as a quality worth bandying about, it’s been on the verge of extinction for decades.

If we do succeed in wiping ourselves out more generally, how many of Anthony Gormley’s sculptures might be left behind to “materialise the place at the other side of appearance where we all live”? Or to amend Gormley’s statement: used to live.

With many laudable aims, Gormley is far from being the most pointless of Turner Prize-winning pretenders and jokers. In fact, it’s a shame given the Angel of the North’s industrial scale and pretensions that it wasn’t built about a central axis. Then it could at least have been wired up to the national grid. Its spinnings would have been impressive, practical and hilarious too – an idea so obvious and striking, that I feel sure I must have seen a cartoon or video depicting this? Although his clunky birdman is so much less graceful and inspiring than the average wind turbine, imagine a whole hillside of them twirling like dervishes!

It does seem that humanity – on the one hand like a selfish, thoughtless teenager – on the other, cannot respond to obvious, impersonal threat with more than the speed of a tortoise. Perhaps this creeping paralysis is the result of a long-inbred complacency; of taking economics rather than common-sense as the basis of our way of thinking; of becoming inured to waste and hedonism – all those things multiplied by the 1980’s.

6

It saddens me that in the urgency of Climate Emergency and rants against the Gimmick, I have no space to explore the fascinating case of Francis Butterfield[xix] (1905 – 1968) – my other worthwhile discovery at the Leeds City Art Gallery.

Beyond a recess, on the wall of which lounged a life-sized photo of Butterfield himself, wasn’t the entrance to the toilets as my wife assumed, but a room full of his work and thoughts.

Arguably Butterfields pleasing (if mostly derivative) works are as arbitrary and decorative as many another modernist – but the best of them have a calming centre that draws you in – at the very least they are therapeutic . . . and perhaps a great deal more.

The trouble with living mostly in the country is that apart from when Conservative billboards sprout all over the fields of landowners, you can live with the illusion that things could change for the better. Recycling, for example, however inadequate (we should be reusing more and re-manufacturing less) appears well-organized, and by main road junctions the evidence of car-share is apparent. By contrast, in cities and towns, the inevitable impression is more negative, the rushing heedlessness of modern existence so prominent that it’s impossible to imagine how things could change in a hundred years, yet alone twelve or three.

Moving through poorer areas (such as we encountered on the forty-minute walk to our ‘airbnb’[xx] on an ex-council estate), you quickly realise how disenfranchised so many people are. My son lived in the Scotswood/Denton Burn area of Newcastle for several years where there was no faith in recycling and often no way of moving old furniture – which filled many of the front yards in his street.[xxi] Once residents knew who you were, most were friendly and would help you to their last penny. Such areas are almost ghettos and their inhabitants understandably defensive. How were they to know that my background was the same, merely earlier in time? My modified London accent sounds posh to them.

7

The vast shanty town that once sprawled under Ribblehead viaduct[xxii], named Sebastapol (after the 11-month Crimean siege of 1854-55) with grim humour by the navvies subsisting there, could be seen as isolated forbear or distant cousin to the slums and ghettos which enclose many of our cities. In some form or other such areas have persisted since industrialization began. After the Second World War, it seemed that in Britain and other relatively wealthy nations, there was a genuine attempt to combat this – all of which efforts were bound to finally collapse in the 1980’s ethos of selfishness. The “stuff everyone else” mentality Thatcher and her ilk encouraged, which thrives to this day particularly under Tory ‘governments’, is now so engrained in society, that many of the younger generation have little choice but to think nihilistically, hedonistically – many of them too “frit” even to sign petitions. They sense the world is toxic but suspect it’s too far gone to change. Perhaps they are right?

At some level, almost everyone but a self-seeking elite has been disenfranchised, and everything that ever stood, even partly, against this – Trade Unions for example – woefully diminished. After being victimised for so long, it’s hardly surprising that even if we can’t mount any proper opposition, at least the Earth is fighting back. To paraphrase Bomber Harris: “we sowed the wind and now we will reap the whirlwind”– not to mention fire, flood and freeze. We have exacerbated all of these – as no-doubt we are responsible for the increase in cancer due to the cocktail of chemicals we encounter or consume every day, in air, water, food, detergents, cosmetics . . . the list could go on indefinitely.

8

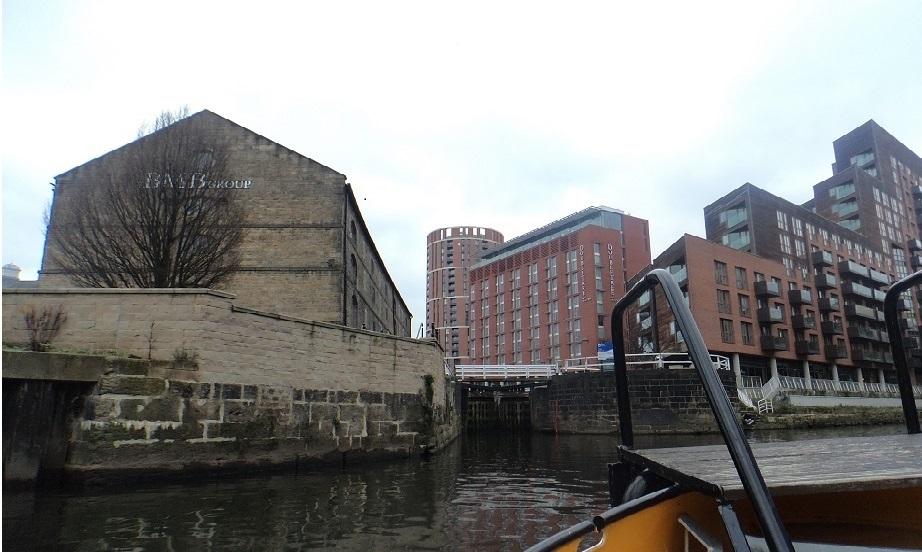

We could spend our free time trawling books or paintings or films, absorbing music from the stately certainty of Bach to the raw anger of King Crimson’s 21st Century Schzoid Man (“Nothing he’s got, he really needs”) but rarely find much that rivals the inclusive beauty of nature. Under frosted avenues or in sun at the land’s edge, the world around that we take for granted, that we are rapidly destroying, is so much greater. Which is why so often I tire of art and culture, or at least of the mediocrity that fills our screens, our libraries, our galleries . . . Instead of art that’s angry, metaphysically yearning or socially accurate, we waste too much time on the trite, the inconsequential and the merely entertaining. Even the grottier side-streets of Leeds hold more interest for me. As for the old canals, seen from one of the free water taxis . . . Leeds may never make it as the Venice of the North, but the intensity present outside, even in a grey January twilight is all too rare in art. As for landscape in less industrially blasted places, the way it gracefully forgives what we, in good or bad faith, have done to it: the railway viaducts and cuttings, the lock gates, the quarries – all appear calm in the face of human pride, destruction and vanity.

“I’d like to live long enough to be around when the nil-witted human race wipes itself out, one way or another. I’d just like to see the look on their stupid faces!”

“They might just all be dancing instead. Perhaps subconsciously we all know our own bad blood; our own self-destructive folly?”[xxiii]

Lawrence Freiesleben, Cumbria, February 2nd 2019

Extinction Rebellion Facebook page: @ExtinctionRebellion

Twitter handle: @ExtinctionR

Illustrations:

1) The Leeds to Liverpool canal passes under the railway near Leeds City Station. 5th January 2019

2) Ribblehead Station, looking roughly north. 4th January 2019

3) Extinction Rebellion image.

4) ‘Above Nenthead’ Gouache & Oil Pastel 57.2 x 76.5 cm

5) ‘Fugitive Threshhold’ Gouache & Oil Pastel 56.3 x 76.2 cm

6) Walking to the airbnb, 4th January 2019

7) Ribblehead Viaduct, looking north west, 4th January 2019

8) Aboard the water taxi approaching Holbeck canal wharf, 5th January 2019

NOTES AND LINKS:

[i] “Anyone who believes in indefinite growth in anything physical, on a physically finite planet, is either mad or an economist.” Kenneth E. Boulding’s (1910-1993)

[ii] Painting a mural for a friend: (the tiger being a bit of a rip-off of Douanier Rousseau’s big cats)

[iii] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/National_Union_of_School_Students

[iv] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Workers%27_Socialist_League

[v] Redfield community – home of community pioneers, dreamers and misfits.

[vii] https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/science-environment-45775309#

[viii] See: A Lost Generation Digression; http://internationaltimes.it/a-lost-generation-digression/

[ix] www.theguardian.com/travel/2019/jan/26/why-i-only-take-one-holiday-flight-a-year-climate-change

[x] The Plan of the Extinction Rebellion (a sub group pf Rising Up) “is to build a large network of groups over the next two to three years to carry out a series of escalating rebellions against a criminal regime – the UK government – which as we all know is taking us down the road to extinction due to its refusal to take emergency action on climate breakdown, extreme inequality, and ecological collapse. This mobilisation is part of an international movement which are taking similar action in other countries.”

Further links: Extinction Rebellion Facebook page: @ExtinctionRebellion and Twitter handle: @ExtinctionR

[xi] www.redpepper.org.uk/confronting-extinction

[xii] www.londongardenstrust.org/features/railings3.htm

[xiii] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Squander_Bug

[xiv] www.scienceandsociety.co.uk/results.asp?image=10175047

[xv] According to http://www.see-a-voice.org/marketing-ad/effective-communication/readability/ the average reading age of the U.K. public is 9. The required reading age for The Sun is 8, whereas for the Guardian it’s 14. I’d be interested to know if these averages are going down – my axe to grind being that our various devices and the predominance of social media generally, are shortening attention spans and increasing our tendency to be stuck in the moment. As the article referenced here is about effective communication, quite reasonably it is concerned with simplicity. While I would not encourage the kind of hollow academic jargon that encourages exclusivity, to what degree does simplicity encourage stupidity? By the criteria of the article referenced, what reading age would be required to arrive here? Is anyone reading this digression from a digression, professor material? If you can get to the end without stopping, perhaps you’re a genius!

[xvi] Threshold to the Kingdom, 2000, on show for the first time in 10 years. www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/wallinger-threshold-to-the-kingdom-t12811

[xvii] A setting of Psalm 51 by Italian composer Gregorio Allegri, presumed to have been composed in the 1630’s during the reign of Pope Urban VIII, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=36Y_ztEW1NE . The scenes and the dissolves between sections of Threshold to the Kingdom appear to have been carefully timed to fit the pattern of this devotional music.

[xviii] https://secretlibraryleeds.net/2014/10/10/the-leeds-tapestry/

[xix] http://www.notjusthockney.info/butterfield-david-francis/

[xx] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Airbnb

[xxi] Despite the run-down nature of the housing, occasionally parked outside and jealously guarded, would crouch a flashy turbo-charged car. I’ve seen the same phenomena in Plymouth, Halifax, Cardiff, Glasgow, Leeds, Liverpool, Bradford, Edinburgh and Blackpool, as well as every compass point of London and many smaller cities and towns. Menacing mobile assets by curtained and declining hovels. Where the money comes from is not clear, though in some cases I’d take a wild guess it’s not legal. Norman Tebbit’s supposed phrase: “Get on your bike” may have been a misquotation, but intentionally or not, the travesty of Thatcherism tacitly endorsed crime and profiteering, from street-corner drug-dealing to insider trading. Anything, to get ahead.

[xxii] oldfieldslimestone.blogspot.com/2013/05/the-shanty-towns-of-ribblehead-after-my.html

[xxiii] From an unfinished story: In the Night My Mind Blossoms You . . .

While air and road travel are indeed heavyweight polluters of our atmosphere, particularly concentrated in our cities, I rarely see any mention of shipping’s role in our self annihilation. Images of vessels floating peaceably far from land, gently transporting the vast majority of our trade across the billowing seas and oceans, mask a far bulkier catalogue of toxic emissions and dirty water, that would quite simply never be allowed on land or near people. Shipping is as dirty, if not more so, than air and motor transport combined, and we are blinded to its virulent impact by nostalgic visions from the age of sail.

Comment by Paul Davidson on 27 February, 2019 at 8:35 amVery good point Paul – my son has pointed out this blind spot to me before. When I was a kid my uncle took us on one of those tourist launches around Southampton docks and the pollution pouring from the bilge pumps (?) of the huge oil tankers was appalling – should have made that a point too – but like a lot of the Digressions, it’s difficult to know where to stop! Perhaps we need to seriously think about bringing back large scale sailing ships? Though not sure how well they would cope with increasingly stormy seas?

Comment by Lawrence Freiesleben on 7 March, 2019 at 8:06 pm[…] [xviii] http://www.redfieldcommunity.org.uk/ Redfield community – home of community pioneers, dreamers and misfits. See: http://internationaltimes.it/the-angst-of-extinction-a-leeds-influenced-digression/ […]

Pingback by The Italian Digression – Part 7 | IT on 2 May, 2020 at 7:01 am