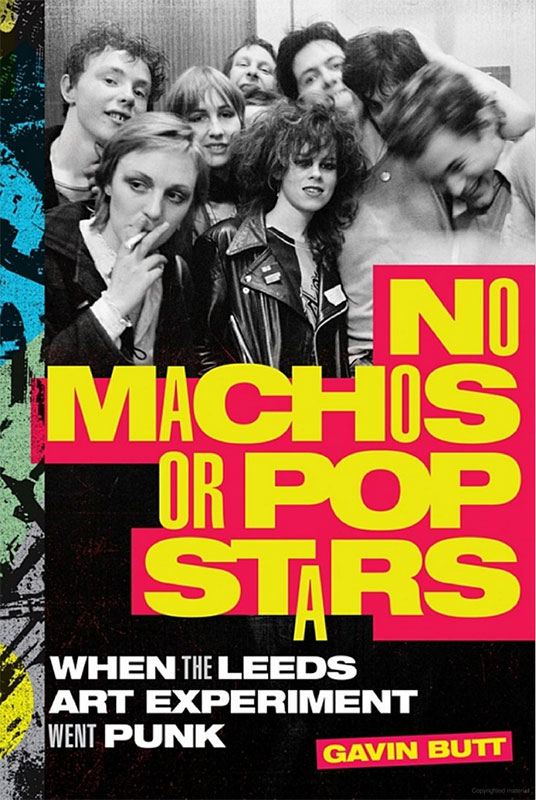

No Machos Or Pop Stars. When the Leeds Art Experiment Went Punk, Gavin Butt

(290pp, Duke University Press)

The few people I am still in touch with from my time in the mid-80s at college in Cheshire, are – like me – all convinced that we had it good. We studied for our degrees on a Combined Arts course where whichever two out of five subjects we were specialising in (or just one in our final year) we took modules alongside students from all those subjects and everyone had access to things like printing facilities and the music studio. In hindsight the college must have been one of the last institutions still offering a multi-disciplined, liberal arts education, with discussion and ideas as important as craft and end result, endless studio time, and generous, interesting staff and technicians.

I say that because, as Gavin Butt makes clear, the government along with younger artists and lecturers, had already moved away from that, the former insisting that curriculum and clear-cut objectives and assessment criteria were put in place, and the latter demanding that theory be as important as art object. This was certainly the kind of thing going on in Leeds in the mid to late 70s, although it is sometimes hard in Gavin Butt’s book to understand if he is suggesting that Leeds bands such as The Mekons, Delta 5 and Gang of Four formed because of avant-garde events, happenings and teaching at the Leeds College of Art and Leeds University, or in opposition to it.

It’s well documented that British art schools produced a lot of musicians and bands. Roxy Music, The Who, and Eno, not to mention a lot of 1950s and 60s jazz musicians, and many others, emerged from art schools around the country, so it feels disingenuous to suggest that bands in Leeds later on were any different, despite changes in teaching methods and expectations, and the loss of institutional independence.

Butt’s book starts by setting the scene at Leeds in the mid-70s, with weird performances executed in front of small, disinterested audiences (or none at all), and students struggling to navigate their own way – without much direction or instruction – through their studies and art-making. Yet, change finally happens, Butt argues, not only because of the arrival of new lecturers who emphasise theory over practice, but also as a specific response to the December 1976 Sex Pistols gig at Leeds Polytechnic. As ever, there are mixed and contradictory reports of who played what and whether the Clash, the Damned or the Pistols were best (the Heartbreakers weren’t anybody’s favourite), whether it was the music or the event that was important, what it changed and how.

Central to the formation of the Leeds bands are two ideas: anyone can form a band (whether or not they can play an instrument), and that music is a good way to take art to the masses. No-one seems interested in painting or sculpture any more, only a few people like Frank Tovey (a.k.a. Fad Gadget) still engages with performance art, and music can be somewhere that theory can be put into practice and audiences challenged and informed.

The last of these always seems, to me, dodgy ground. One ends up with sermons, polemic, diatribes, slogans and persuasion, akin to the sort of dreary things the likes of Art & Language produced as their ‘art’. Thankfully the bands coming out of Leeds wanted to make pop music as much as discuss feminism, capitalism, genre and identity. Ideas and concepts informed the bands formations and songwriting but weren’t always foregrounded, although the early cabaret or burlesque antics of Marc Almond and Soft Cell would contradict that statement, as would the rhetoric, construction and visual packaging of Gang of Four’s songs and music.

And yet, Gang of Four’s awkward and scratchy deconstructed politicised funk could still be danced to, just like Delta 5’s less aggressive music, along with the songs created and performed by the shambolic and inclusive Mekons. Scritti Politti might stick with the theory in interviews and press releases but it didn’t take long before Green Gartside’s lyrical consideration of Gramsci and ‘bourgeois hegenomy’ was put aside in favour of pop stardom and higher production values on the back of signing with a major label. Bands would soon realise they would be better placed for stardom elsewhere and left Leeds for London or other cities.

No Machos… is a fascinating, informed and highly readable account of a specific geographical example and a specific period of time, but I feel similar events, personal and social upheavals and changes were happening everywhere (if sometimes a few years before or after). In my own case the original big-band incarnation of the Thompson Twins left college as I arrived in 1982, the singer of Half-Man Half-Biscuit was in the year below me, two guitarists in my year were already established session musicians, and there were any number of bands forming, breaking up, practicing, performing and recording. Since these bands included drama, dance, crafts, art and writing students, all sorts of influences and approaches resulted.

Outside my college was of course another world, the 1980s world of zines and DIY cassette releases, and an amazing local record shop; a world of local punk bands, and tape experiments, with outings to Stoke-On-Trent, Liverpool, Manchester and Keele University to see live music. Local gigs could see a hardcore punk band, followed by an event where a wall of flickering detuned televisions was accompanied by noise loops and improvised guitar, with a synthesizer trio to end the evening. I remember one band even broke up live on stage supporting Martyn Bates from Eyeless in Gaza! The main influences (which was a shock to this London boy) seemed to be anarcho-punk, Hawkwind, Chrome and Cabaret Voltaire.

Politics and art theory may have been different then, but they have always changed and evolved to refocus on current issues and debates, as well as adapting to deal with new technologies, art forms and ideas. The university where I teach now is trying to re-introduce more collaboration through cross-curricular modules and inter-disciplinary activities, and there are still debates, questions and discussions, still those who want to be popstars or make new experimental music. And thankfully, there are still some who want to change the world, just like those in Leeds did back in the day.

Rupert Loydell

Hello Rupert,

Interesting piece and perspective, glad to hear creativity is alive and challenging. Why do you think it’s doing so less often in the mainstream or am I rose tinted…?

Comment by George on 25 October, 2022 at 11:23 amHi George, thanks for the comment and question. My own ‘take’ would be that the mainstream is smaller than ever, because the web etc has meant it’s easier to make music and access writing/music, which means there is a lot more stuff for smaller and/or specialist audiences. If you’re into the sound of road drills then you can find someone else who is too… you don’t need any major record label , or even an indie one, to release it. There also seems to be a certain apathy about music in general – young people seem to prefer games and online films – and an acceptance of mainstream culture that wasn’t there 30 or 40 years ago; also a sense of stuff being disposable and temporary rather than life-changing or life-affirming. But I’m old enough to be out of the loop!

Comment by Rupert on 25 October, 2022 at 8:59 pm