The Repressed, Deviously, in Masquerade

YL: Kafka wrote many poems, but he did not call them poems. There is no need for you to leave the house. Stay at your table and listen. Don’t even listen, just wait. Don’t even wait, be completely quiet and alone. The world will offer itself to you to be unmasked; it can’t do otherwise; in raptures it will writhe before you. This is an aphorism constructed of mystic stations. One might call it a prose fragment or bit of wandering mage come to roost. I myself have no objection to calling it a poem. But specifically it is an aphorism constructed of mystic stations. Like stations of the cross. When I read There is no need for you to leave the house. Stay at your table and listen, I think of Pascal’s precept, that all our difficulties arise our inability to sit quietly in a room, alone. That if one could be still enough, if one could endure one’s own company, if one could remain present. If only one could. If only. Kafka is addressing our tendency to flinch. We flinch, for self-preservation, when we are with ourselves too long, because it quickly becomes too much. The boredom, the suffering, the restlessness. Don’t even listen, just wait, he says. Then, immediately: Don’t even wait, be completely quiet and alone. He is a reluctant Messiah, our Franz. Distrustful of his own authority. He must immediately make qualifications, equivocate. He bids us ‘wait’. Then, backpedaling hurriedly, insists: Don’t even wait, be completely quiet and alone. Because even the most modest expectation might scare it (the ‘there-world’) away.

We sometimes strain for feeling as though sitting outside a foxhole with our guns, waiting for a fox. The fox never leaves. It will never leave. Because it knows it is being hunted. Watched-for. Expected.

Those lines, ‘The world will offer itself to you to be unmasked; it can’t do otherwise; in raptures it will writhe before you…’ bring me goose bumps and, yes, tears and, yes, I do think a sublimated eroticism is partly accountable for the charge, the zap. I think of Nietzsche, especially in Zarathustra, ‘the waves are heaving breasts,’ etc. That from a man who may have seen all of one pair throughout his adult life. In a letter to Milena, Kafka will write: To try and catch in one night, by black magic, hastily, heavily breathing, helpless, obsessed, to try and obtain by black magic what every day offers to open eyes!

Alas, poor Milena! Imagine being the recipient of such a letter, imagine being a young woman learning about her young man, and receiving such a letter. How could it not sting? And imagine being the one who had sent such a letter. Imagine being the young man. How can such a letter ever be lived down? It is too big to regret. It is Van Gogh’s ear. It is too much to take back. It is yesterday’s moon. Sometimes a voice out from the chaos of spirits cries and one finds oneself having written. Can one say that? Or perhaps it is only poetry. The young man, in fear of the young woman, writing of sack-cloth and ash, wishing his body would be burnt away. Nothing more to it. Whatever is dammed must find another outlet. Whoever is damned must find another heaven.

The Ecstatics from my tradition, the Persian tradition, could be wildly erotic, but because they were addressing themselves to God they felt safe. For Kafka, the mystic ritual he called ‘writing’ was his safe zone. Where he could let it all out and breathe light like a spirit fish swimming between stars. Mysticism is desire, like everything else is, and the desire of mysticism is a flaming arrow launched toward union. That union of the mystic, fire reaching to fire, no less than any carnal union, is an erotic experience. An ecstasy in the specifically Greek sense of ekstasis, meaning ‘outside oneself.’

Part of what we read in Kafka is too personal. Tedious neurasthenic considerations. Documents for the doctors at the Sanitarium of Hypochondria. The repressed, finding its way, surfacing, deviously, in masquerade. And part of what we read in Kafka is a universalized, lived, sensuality. Shy experience of the self as other. Veiled encounters with the beloved. Butt-naked tusslings. And why not? To get there means ‘union’, long longed-for (or, it may be, ‘reunion,’ long hoped for) and it induces bliss. The ‘impotent’ who eroticizes the world, for me, he is the prophet. And I’m not the only one who thinks this. Lawrence Durrell, in his novel Justine, writes, “the sick men, the solitaries, the prophets [!]…all who have been deeply wounded in their sex.” The statement lacks proportion, but there is truth in it. To be wounded in that way is to dam a furious river that begins, as Rilke tells us, ‘in the sky.’ ‘Making music is another way of making babies,’ writes Nietzsche. And yes that is sublimation and yes it does color thought, but doesn’t it color thought in wonderfully feverish flesh tones and isn’t all that fleshly frailty and failing a living part of Kafka’s meaning for us—a necessary aspect of its divinity? Isn’t all that partly its sacrament? And isn’t the chaos and aren’t the death-thralls just autumn leaves in their season?

As for your last question: Where does one draw the line in turning to these literary figures for answers or sustenance, or for that matter tips on elegant living? Where does Kafka end and literature begin? Would I read Kafka’s unpublished journals? Yes. Would I read Kafka’s laundry list? Yes. Where does one draw the line? At what he agreed not to burn? I am with Max Brod. Everything Kafka wrote (or for that matter said or did) is interesting because whatever he does, he is still doing the work. And the work is just self-work, but so, too, could be said of anything any of us do, in any capacity, fence-mending, love-making, book-binding, that it is just self-work. With Kafka we are given the opportunity to witness a self-work master-technician seeking, with elegant precision, his own hinterlands, focused in a state of such contained urgency, that it is almost a trance of clairvoyance . Kafka is us, without the lying.

Shouldn’t that change the way I read him? It should. And it does. It ups the volume on everything. Even if he only clears his throat, it rings like thunder. Because the fact of the matter is he has something thunderous in him to say, and the fact of the matter is we know that he does. That is the point. Some of this stuff, sure, it can be more navel gazing, more convolutions, but what we cannot fail to recognize in Kafka is that this is a guy who is wrestling with his angel, and that commands our attention. What he is up against, so are we up against.

In the two slender notebooks, those two blue octavo notebooks, meant for school-children, we get his private conversations. And in private conversations all of us tend to think more childishly, more innocently, more directly, about hope and suffering, good and evil. If Kafka were to have translated those private conversations into public fictions or such-like, something that could have been folded twice and shot skyward under cloak of literature, his style would have to have been necessarily more self-conscious, more ambiguous. But, because these were entirely private conversations, and because they were left so, they became perfect mirrors. Looking glasses. Beyond the fairy tale of the bardic. Verging on the estate of the vatic.

Listen, now: Aphorism #16: A cage went in search of a bird. That’s all of it. That’s all there is. No root. No soil. Bloomed in thin air. Sometimes from Kafka, we get a truth that just is. A white, as it were, flower lapel that is not worn in irony.

That cautionary reprobate Charles Baudelaire once wrote, “The greatest wile of the devil is to convince us that he does not exist.” This echoes many of Kafka’s octavo notebook aphorisms about the idea of evil. It’s almost the cleric or the choir boy in Kafka writing at such times. At another level, though, it is as if he is some august theologian, transmitting a soul-map in code.

*******************************************

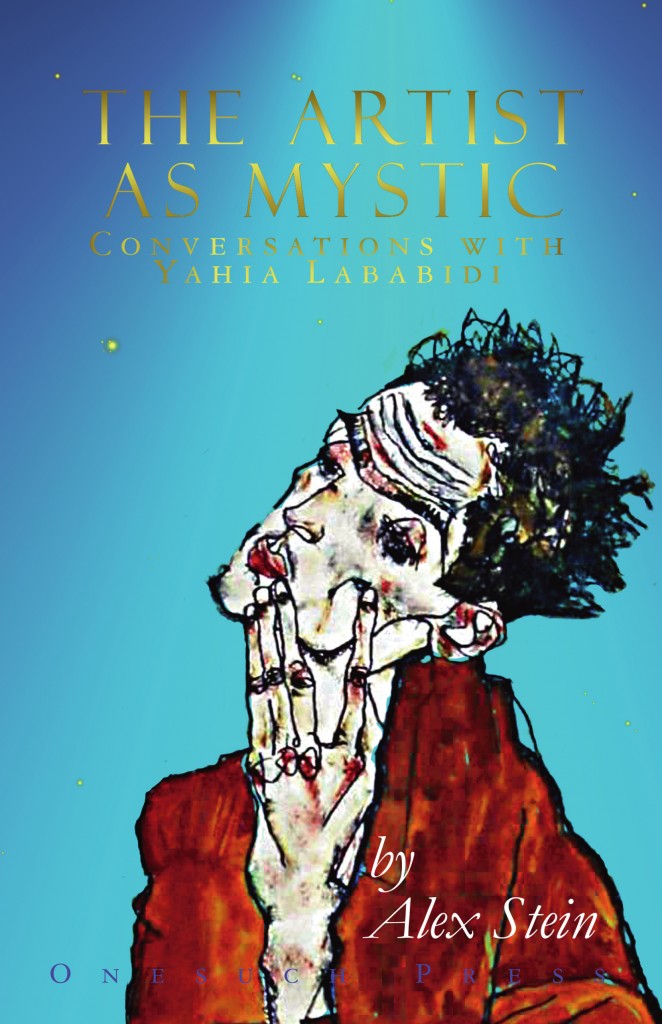

The Artist as Mystic is a set of lyric conversations between aphorists Yahia Lababidi and Alex Stein. These conversations constitute what Australians call a ‘Songline’—a set of sacred songs that allow the reader/listener to navigate through an unknown terrain, in this case, populated by tortured and ecstatic souls: Kafka, Baudelaire, Nietzsche, Rilke, Kierkegaard and Ekelund.

These visionaries are masterfully evoked in this very fine work of biography and criticism.

But these writings are more than the sum of notes on a page, they are song. The Artist as Mystic passes the test of all great writing, not only to delight, but to leave us knowing something of the subject, and ourselves, that we hadn’t considered before.

Praise for The Artist as Mystic

“Few writers pay such passionate due to their literary forebears as Yahia Lababidi, and in these conversations he summons up the great seers—among them Kafka, Nietzsche, Baudelaire—with an immediacy and a vividness thatmake them seem his, and our, contemporaries.”

John Banville—winner of the Man Booker Prize 2005 and the Franz Kafka Prize 2011

“I have never encountered a book like The Artist as Mystic and I’m still not convinced that any modern person could be as reflective and erudite as Yahia Lababidi. But whether Lababidi is real or fictitious, the pleasures of this book are undeniable. It provides intimate insights into writers such as Nietzsche, Kafka, Kierkegaard and Rilke and offers the

deepest intellectual rewards of its own.”

David Bezmozgis—author of The Free World

“Yahia Lababidi has no patience for easy bows and judicious curtseys. He gives intimate brotherly address to the writers who have made him and, doing so, recovers the sense of mattering—the passion—hat has always fired the deepest reading, and the writing that lasts. Much heart here, but also a shrewd experienced acuity and an irresistible grace of expression.”

Sven Birkerts—author of The Other Walk: Essays and The Gutenberg Elegies

do ya need another ‘religion-junkie’..??

Comment by JoHnny de-Lux on 7 September, 2012 at 6:52 pm