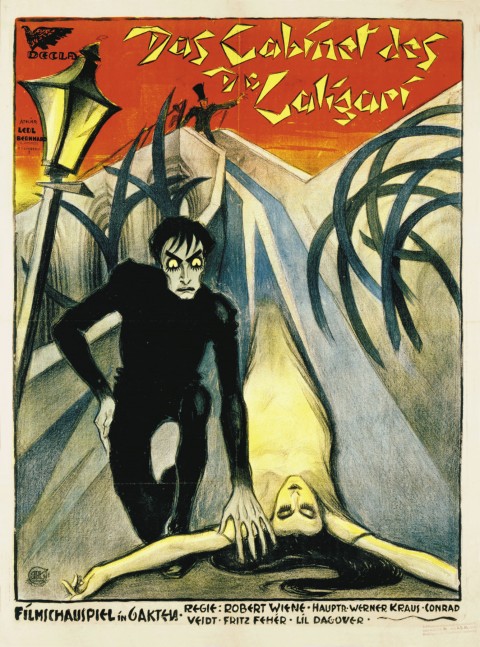

In early 1920, posters began appearing all over Berlin with a hypnotic spiral and the mysterious command Du musst Caligari werden — “You must become Caligari.”

The posters were part of an innovative advertising campaign for an upcoming movie by Robert Wiene called The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari. When the film appeared, audiences were mesmerized by Wiene’s surreal tale of mystery and horror. Almost a century later, The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari is still celebrated for its rare blending of lowbrow entertainment and avant-garde art. It is frequently cited as the quintessential cinematic example of German Expressionism, with its distorted perspectives and pervasive sense of dread.

Like many nightmares, Caligari had its origin in real-life events. Screenwriter Hans Janowitz had been walking late one night through a fair in Hamburg’s red-light district when he heard laughter. Turning, he saw an attractive young woman disappear behind some bushes in a park. A short time later a man emerged from the shadows and walked away. The next morning, Janowitz read in the newspapers that a young woman matching the description of the one he had seen had been murdered overnight at that very location.

Haunted by the incident, Janowitz told the story to fellow writer Carl Mayer. Together they set to work writing a screenplay based on the incident, drawing also on Mayer’s unsettling experience with a psychiatrist. They imagined a strange, bespectacled man named Dr. Caligari who arrives in a small town to demonstrate his powers of hypnotism over Cesare, a sleep walker, at the local fair. A series of mysterious murders follows.

Janowitz and Mayer sold their screenplay to Erich Pommer at Decla-Film. Pommer at first wanted Fritz Lang to direct the film, but Lang was busy with another project, so he gave the job to Wiene. One of the most critical decisions Pommer made was to hire Expressionist art director Hermann Warm to design the production, along with painters Walter Reimann and Walter Röhrig. As R. Barton Palmer writes at Film Reference:

The principle of Warm’s conception is the Expressionist notion of Ballung, that crystallization of the inner reality of objects, concepts, and people through an artistic expression that cuts through and discards a false exterior. Warm’s sets for the film correspondingly evoke the twists and turnings of a small German medieval town, but in a patently unrealistic fashion (e.g., streets cut across one another at impossible angles and paths are impossibly steep). The roofs that Cesare the somnambulist crosses during his nighttime depredations rise at unlikely angles to one another, yet still afford him passage so that he can reach his victims. In other words, the world of Caligari remains “real” in the sense that it is not offered as an alternative one to what actually exists. On the contrary, Warm’s design is meant to evoke the essence of German social life, offering a penetrating critique of semiofficial authority (the psychiatrist) that is softened by the addition of a framing story. As a practicing artist with a deep commitment to the political and intellectual program of Expressionism, Warm was the ideal technician to do the art design for the film, which bears out Warm’s famous manifesto that “the cinema image must become an engraving.”

The screenwriters were disappointed with Wiene’s decision to frame the story as a flashback told by a patient in a psychiatric hospital. Janowitz, in particular, had meant Caligari to be an indictment of the German government that had recently sent millions of men to kill or be killed in the trenches of World War I. “While the original story exposed authority,” writes Siegfried Kracauer in From Caligari to Hitler: A Psychological History of the German Film, “Wiene’s Caligari glorified authority and convicted its antagonist of madness. A revolutionary film was thus turned into a conformist one — following the much-used pattern of declaring some normal but troublesome individual insane and sending him to a lunatic asylum.”

In a purely cinematic sense, of course, The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari remains a revolutionary work. You can watch the complete film above. Or find it listed in our collection, 1,150 Free Movies Online: Great Classics, Indies, Noir, Westerns, etc..

Related content:

Fritz Lang’s M: Watch the Restored Version of the Classic 1931 Film

Metropolis Restored: Watch a New Version of Fritz Lang’s Masterpiece