By Heathcote Williams

Colin Wilson read this extraordinary book at a single sitting. He can’t have been an exception. Malcolm McNeill’s ‘Observed While Falling: Bill Burroughs, Ah Pook and Me’ sweeps you up into a multi-layered adventure that presses almost every button: it’s philosophy; it’s science fiction and it’s science fact. It plays astonishing tricks with reality. It’s a wild phantasmagoria but, more specifically, it’s an account of the creation of that legendary graphic novel, ‘Ah Pook Is Here’, the great ‘lost book’ of the last century. It’s a literary case history that belongs on every counter-cultural bookshelf.

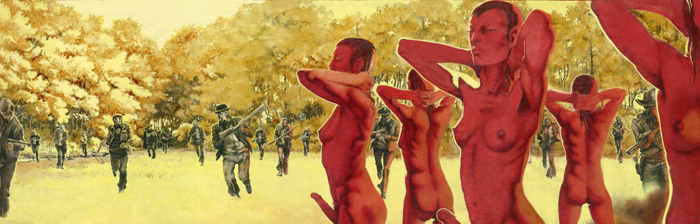

‘Ah Pook Is Here’ was a legend for a number of reasons: McNeill’s cinematic realism marked a leap from comic book to mythical graphic novel. He created a style to match the intensity of the material. It was the seminal prototype for what is a now familiar genre.

It’s legendary too because, like Jodorowsky’s film ‘El Topo’ that was smuggled across the Mexican border foot by foot, Ah Pook would tantalizingly appear and disappear from public view. Was such and such a version of Ah Pook the complete one? was this the definitive edition? Why was one edition of it printed with no graphics, just a text only version?

Like ‘The Quest for Baron Corvo’ there has been a continuing quest for the authentic and ever elusive ‘Ah Pook is Here’.

McNeill’s ‘Observed While Falling’ is a roller coaster of a read, recounting the struggles which the authors had to get it published as they’d intended, often with obstacles being placed in their path by the very people who one would have assumed to be sympathetic. Although, given the ambiguities of the book’s subject matter – namely the antics of the deadly Mayan Corn God – perhaps such things were inevitable. Dark forces and unsettling synchronicities would come into play. Their project was dealing, after all, with the Mayan codices’ books of the dead and they are, in McNeill’s words, “the battered legacy of millions of souls long gone.”

The graphic novel’s co-creator was the visionary English artist and writer, Malcolm McNeill. His collaborator was the “écrivain maudit” William S. Burroughs. McNeill would say of Burroughs in an interview with Big Bridge magazine:

“One of the sincerest, most considerate, normal guys I’d ever met—and of course the smartest. I knew I was in the deep end the moment I met him, but of what and how deep I had no idea. It didn’t take long to realize I even had that wrong. Deep under normal conditions implies a bottom. Bill’s time /space orientation precluded such a thing.”

McNeill used his pencil, as he puts it, for “a kind of archaeological digging that reveals ‘new configurations of thought.” And miraculously he’d find that “Like a dowser’s rod, it seems to know where and when to dig in order to access currents of ideas relevant to the digger.” As a result, McNeill’s work has been said to “provide key insights into the mind of the writer” (although controversially, and unforgivably, it would prove too much for the obstructive gatekeepers of the Burroughs Estate – hence the novel’s checkered career. They were so disobliging, in fact, that McNeill was at one point sorely tempted to bid goodbye to the entire artwork of Ah Pook by torching it. Mercifully, however, this did not happen.)

McNeill and Burroughs began their collaboration in London in 1970 and it would continue up until Burroughs’ death in the US in 1997. “Art,” Burroughs said, “makes us aware of what we know and what we don’t know that we know.” In Malcolm McNeill Burroughs was to find his ideal collaborator in a joint exploration of the unknown; in their both venturing where both angels, and indeed devils, might fear to tread.

“The purpose of writing is to make it happen” Burroughs would write during their collaboration and, in order to research ‘Ah Pook is Here’, McNeill and Burroughs spent a day together poring over the Dresden Codex in the British Museum.

The Codex is the key to the ancient Mayan mindset, to that priestly government’s methods of controlling its population and their thoughts, and to the unholy powers ascribed to its death cults; to the removal of beating hearts – the hearts that measure time – from the Mayans’ sacrificial victims. After a lengthy immersion in this alien but telling culture, McNeill and Burroughs would end up making “dead fingers talk.”

In other words they’d bring the dead back to life. Neither ‘Ah Pook is Here’ nor McNeill’s book are for the faint hearted.

In the first two sentences of their collaboration, ‘Ah Pook is Here’, Burroughs was to write: “The Mayan codices are undoubtedly books of the dead; that is to say, instructions for time travel. If you see reincarnation as a fact then the question arises: how does one orient oneself with regard to future lives?”

The Mayan codices have long been regarded as something more than anthropological curiosities. Had they not predicted the precise year when Hernán Cortés would arrive in the Americas? Their appeal to Burroughs was obvious:

“As a writer”, McNeill notes, “Burroughs was in fact prescient. He had the ability to ‘write ahead’. I experienced that phenomenon first hand many times while working on ‘Ah Pook is Here.’ Fictional events in the text would materialize in real life. Very specific correspondences, not just similarities. Such events might suggest that things are already in place and that with the right combination of words they can be made to reveal themselves ahead of time.”

McNeill explains, “That’s what Bill’s ‘Cut ups’ were about: “Cut the word lines and the future leaks out.” as he put it. Unlike other forms of augury — cards, coins, animal guts etc. Cut-ups literally cut to the chase.”

And McNeill and Burroughs would find that such phenomena, such coincidences, such synchronicities would get weirder and weirder as their graphic novel took shape. The more they studied the Mayan codices with their emphasis on how to “access future time” the more nature would imitate art. The more the things that they imagined happening, the more similar the things that would actually happen as if they were conjuring up an apocalypse with Burroughs’ ball-point pen and McNeill’s pencil. As with Flann O’Brien’s ‘At Swim Two Birds’ and ‘The Third Policeman; Ah Pook’s characters would interact with their creators.

Very early on they’d map out their dramatis personae and the projected book’s ingredients: “By the end of the year, “McNeill writes, “the text included the FBI, hijacked airliners, Mexican bandits, and Virus B23.” The latter was designed to be handy for the reintroduction of extinct animals – and it was also to be dropped on the cities of the world whereby, as Burroughs proclaimed, “Any sex act can now create life. The biologic bank is open.” As a result new species would spring up designed to replace redundant humans.

There was to be an old Gombeen woman and Cumhu, the Lizard boy

(the Lizard Boy was to have sex with shrews). There were to be boys on hang-gliders “powered by nitrous farts” and there’d be ejaculating bats; there’d be a Mexican bar on the moon called ‘Los Alamos; there’d also be stoned priests; Xolotl the Salamander; Ouah the cat; the Painless One; ‘Philde’ the time-traveling drug, and a “Mr Hart the Ugly American who would live forever.” Frozen and lonely and with “no one to thaw him out.”

Time-traveling mutants were to be skinned alive by lobster-clawed Mayan priests and then baked inside giant metal centipedes; Mayan priests would shape-shift by dressing up in the skin of their victims; Piccadilly Circus billboards were to owe more to Wilhelm Reich than to ad agencies by their showing full-on sex scenes (this being more honest than the titillations currently sponsored by cosmetic companies – all promise and no delivery). Ah Pook would reign.

Hieronymus Bosch’s Garden of Earthly Delights would be the setting for the final scenes in which the protagonists board the Marie Celeste and sail off into the sunset. “On the walls of the ruins of Hearst Castle, the graffiti read, ‘Ah Pook was Here.’”

It was all to be realized in stunning detail by McNeill. The creation of their apocalyptic graphic novel would turn out to be quite a trip. In 1970 LSD was very much in the air. Counter-intuitively however, Burroughs, who’d had a couple of bad experiences with it, denounced it as, “horrible stuff. I just don’t want to know about acid.” Famously he’d insist (when clean) that, “anything that can be done chemically can be done by other means.”

Yet, as McNeill points out, “LSD ironically provided the inroad to his worldview. It clearly demonstrated the dichotomy of absurdity and terror that characterized his writing… The drug exposed the tenuous nature of agreed-upon reality. How the minutest quantity of chemical substance – something no bigger than the head of a proverbial pin – could change one’s perception entirely. It confirmed in the most dramatic way, that everything was subject to question.”

However, although he had forsworn LSD, Burroughs did derive inspiration from another alien source, namely the Orgone Accumulator Box that he had in his London flat. McNeill describes the Burroughs’ ritual: “He got in shape every day with a spell in his Orgone Box, an incongruous, Tardis-like structure in his bedroom, oddly reminiscent of an outhouse. It was a homemade affair comprised of alternating layers of organic and inorganic materials – wood and metal, basically, with some rabbit fur thrown on top for good measure – with a door and a seat inside like a privy.”

Thus did Burroughs engage with the quintessential energies of the universe before joining forces with McNeill to do graphic battle with the authoritarian demons of chaos whom he saw as having been in control since Mayan times, and who sorely needed to be dislodged. “No organism in the history of the planet ever did anything unless it absolutely fucking had to.” Burroughs said. Burroughs and McNeill would force them to, through their art.

“Coming to terms with his [Burroughs’s] unique methodology,” McNeill said, “while simultaneously trying to produce images that were commensurate created a learning curve like I’d never known. These were the most intense, far-flung ideas I would likely ever encounter.”

Burroughs would declare, “I am a map maker charting unexplored areas of the psyche” and, thanks to McNeill’s collaboration, Burroughs’ own psyche becomes a remarkable visual reality in ‘Ah Pook is Here.’ But it wasn’t an easy ride: there was the awkwardness of Burroughs being gay and McNeill not.

“You’d have a great career as a homosexual,” Burroughs would say when hitting on his youthful collaborator only to be politely rejected. McNeill also makes clear that “Making images wasn’t a matter of turning on a faucet every day and having it happen. It was subject to a kind of internal weather as unpredictable and unalterable as real weather.”

The pair were given the brush-off by obtuse publishers belittling their work as a “comic book.” Their agent Peter Matson would say at one point despondently and forbiddingly, “this project is too far out and/or expensive for the more conventional publishing houses.” (his discouraging verdict was delivered after they’d both been working on the project for seven years).

There was also Burroughs’ alarming penchant for interrupting proceedings to place elaborate curses on those who offended him, such as the hapless New York Times critic, Anatole Broyard (whose name derived from the French word for fog, “brouillard”.) Burroughs subjected him to “the Curse of the Blinding Worm.”

Work would cease while Burroughs would intone his diabolical imprecations with the aim of fogging Broyard’s vision quite fearless of the repercussive risks attendant on such curses, i.e. their bounce back (Burroughs had notoriously put a London coffee shop out of business by such dastardly means).

And then there was Burroughs’ culinary skills or rather the lack of them: a typically bleak meal in Burroughs’ Duke Street flat might be broad beans followed by a second course of baked beans. (McNeill magnanimously describes such meals as “memorable”. Burroughs would also have a junkie relapse when a shipment of Iranian heroin turned up in New York.

Ah Pook’s gestation was precarious but thanks to McNeill’s determination and courage this voyage of discovery was made manifest, and thanks to Burroughs himself ‘Ah Pook is Here’ has claims to be one of the most vivid manifestations in the Burroughs canon – the work that most accords with his view that “there are no rules, no procedures, no correct words, for reliably dealing with this life, let alone the next.”

Those who come at the world and turn it upside down with their artistic guns blazing as McNeill and Burroughs have done, and, as in the case of Malcolm McNeill still do, are pearls beyond price. For all the comedy (and, being wittily written, there is much in ‘Observed While Falling’ to savour) it is a serious book. It is also lavishly illustrated. Be prepared for serious ripples in your psyche.

Heathcote Williams

Malcolm McNeill, ‘Observed While Falling: Bill Burroughs, Ah Pook and Me’, Seattle WA.: Fantagraphics Books Inc., 2012

I believe, and, sincerely hope, that I have ALL of Mr. McNeill’s art and writings, starting with his collaboration with Mr. William Burroughs, ‘AH POOK IS HERE’. Try as I might to encourage others to enjoy self-enlightenment through both Burroughs & McNeill’s art and words, alas, these ‘others’ seem to be uber distracted by the next ‘blip’ on their screens. But, then again, when one considers the powerful reach of today’s visual techno-trickery, why, oh why, hasn’t ‘AH POOK IS HERE’ been made into a film!? Art directed, of course, by Mr. Malcolm McNeill!

Comment by BRIAN FRANK CARTER on 14 January, 2015 at 4:02 pmI am actually grateful to the owner of this website who has shared this enormous post at at this time.

Comment by Ryse Son of Rome final release download on 20 January, 2015 at 8:16 am