“Life is a sexually transmitted disease,

and the mortality rate is one hundred percent.”

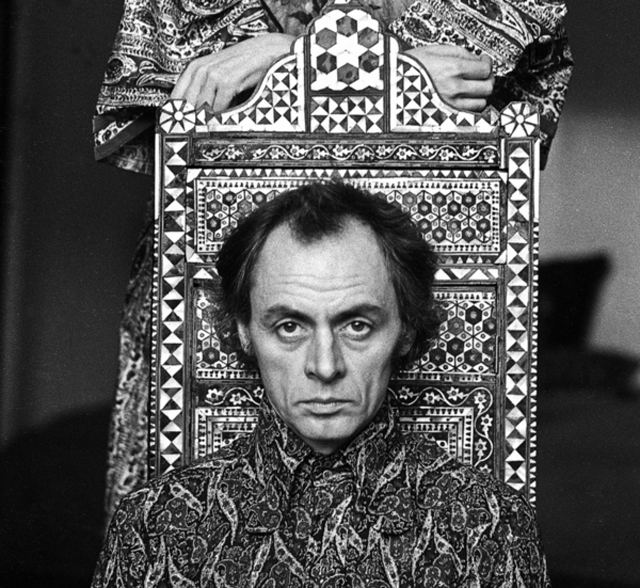

R.D.Laing

On Alitalia Airlines, on my way from Rome to London, I read that Foucault had died in Paris. On the twenty-fifth of June of 1984 the world had lost one of its prestigious philosophers.

When I got to the Laing’s house where I would be staying for a week, Ronnie opened the door and said, “Ah, here comes the cabaret.” It was what he called me at times. The Cabaret.

Relieving me of my guitar he said, “Come in, come in. Jutta’s not here just now. I don’t know where she is. I’ll take you to Adam’s room. He’s away so that’s where you’re sleeping.”

I loved his Glasgow accent.

As we climbed the carpeted stairs to the top of the house I told him of Foucault’s death. I knew they were friends who mutually admired each other and that this would be disturbing news.

All the pain of the world echoed in Ronnie’s sigh.

We went downstairs to the kitchen and he offered me a cup of coffee.

“How beautiful your garden looks,” I said as my eyes feasted on the bushes of roses and many other flowers that framed the green lawn. Jutta and I had taken tea and cake there on many occasions.

“Yes, Jutta has made a lovely job of it,” he said and added, “I don’t know when she’ll be coming back, so why don’t I take you to some of the best-known pubs in London.”

I didn’t tell him I hated pubs. They reminded me of all the bad times I’d had in them when I was married.

“Lovely, thank you.” I knew he was being gallant and offering me good times.

At the Spaniard’s Inn in Hampstead I told him, “Our dear friend, Julian Beck, has been diagnosed with incurable cancer.”

Ronnie sighed that profound sigh of his again.

We carried on from pub to pub where Ronnie, true to his reputation, drank with gusto, as I sipped at the red house-wine.

It was a lovely day so we sat outdoors at the Flask in Highgate and had scotch eggs.

Then Ronnie said, “Let’s go to a friend’s house.”

He bought a couple of bottles of champagne and hailed a taxi.

The friend’s house was gloomy. Messy, with a general air of uncleanliness. There was another young man there who rolled a stream of joints.

Suddenly Ronnie began to insult me. “You should learn to play the guitar properly,” he accused.

I couldn’t disagree with him about that.

“Your performance is pathetic,” he continued.

Although he had never been aggressive towards me he had a reputation for attacking people, and I didn’t let his words faze me.

The two friends looked at me, at him, at each other and I thought they were going to jump out of their skins. But I knew how to shield myself from Ronnie’s slings. I simply let the arrows fly past me never allowing them to wound me.

“And as for your song Dirty Lover. It’s rubbish.”

“Maybe I should write one for you Ronnie,” I said laughing.

It eventually became a contest between us and I thought to myself, I know how to get the better of you Dr Laing, your words can’t touch me and it pisses you off. He wanted a challenge and I wasn’t going to get drawn into it. I reminded myself of Ronnie’s aphorism, ‘Don’t take it serious, it’s just an experience.’

I felt sorry for the friends who were more and more embarrassed. The atmosphere in the house was that of doom.

Then Ronnie stood up from the dilapidated, brown uneasy-chair from where he had been facing me. Drink in hand, he said, “I want to toast Michel Foucault, who died today.”

I got up too. “To Foucault,” I said, extending my flute of warm champagne towards Ronnie.

Unashamed tears tumbled down his mobile face that now resembled the crumpled, distorted, wet mask of tragedy.

“And I also want to make a toast to Julian Beck,” he sobbed.

Now I was weeping also. Weeping for my beloved Julian, whom I would never see again.

“To Julian Beck,” I echoed.

Then it was over. We sat down and for a while no one spoke.

It was getting late, the boys went to bed and Ronnie lay down on the dirty brown rug that covered the floor.

“Come and lie down next to me,” he said.

“No way. Ronnie, please take me home.”

He made his offer several more times, and on my final, ‘please take me home’, he sighed, heaved himself up off the floor and said. “I wouldn’t do this for anyone but for you Hanja.”

Walking home through empty streets at dawn, hearing the twitter of waking birds and looking forward to my comfortable bed, I felt exhausted and completely at peace. Ronnie’s dramatic farewell to our friends had been a catharsis. It had been a cleansing ritual, such as shamans perform.

“What is the illness of our age, Ronnie?” I asked.

“A lack of folly,” replied the Master Shaman.

***

In the late morning Jutta, hearing me come down the stairs, called from the kitchen, “Go into the sitting room, I’ll bring the coffee up.”

I lounged on the comfortable couch in the spacious room elegantly fashioned by Jutta in barley tones and Asian rugs.

Books and papers everywhere: dropped and scattered here and there in spite of Jutta’s efforts to keep things in their place.

“He won’t allow me to touch anything,” she often lamented.

On the marble mantel above the fireplace a small jade Buddha smiled amongst other precious objects and photographs that please the eye and touch the imagination.

The solid, pine table in front of the window was cluttered with his diaries, Chinese note-books, newspaper cuttings, elegant writing tools, a Victorian ink-well, a large copper ashtray, an empty wine glass.

Music sheets and albums were piled on top of the black Steinway whose ivory keys played such an integral part of Ronnie’s being. The piano was Ronnie’s medicine – he was forever drawn to it. At parties he would play all night. Boogies and classics; blues and Liszt; Irving, Cole and Noel Coward. The accompanist of every singer’s dream, he knew them all: Schubert’s lieder for Jutta’s nightingale voice; My Foolish Heart, for sentimental me; Blue Moon for Judith Melina; Spring Can Really Hang You Up The Most, for Fran Landesman. He too would sing with deep, guttural, melancholic timbre.

Jutta came in with the coffee pot and mugs and asked, “So what did you do last night?”

As I began recounting, Ronnie joined us. He looked like a shy, guilty kid. His hung-over, Charles Boyer eyes, gazed out through the bay window, across the flower-patched front lawn, onto the Japanese birch whose ripe-plum tinted leaves curtained off the Eton Road.

“I don’t remember last night at all. Did I do anything out of place?” He asked.

“No, it was very nice. I was just telling Jutta about our pub crawl.”

“Ah, yes, yes,” he muttered as he poured himself a mug of coffee.

The three of us sat in silence for a while.

Then Ronnie got up, sighed and said, “Well, I’ll be seeing you.” And left.

Beautiful Jutta sighed.

Sadly, that week I stayed with them was my last visit to the exhilarating Laing household.

I’d had many quality times there amongst cultured, talented, fine-looking people. We were bathed by a bewitching light, gifted, besotted with our Muses, having fun, feeling free. We smoked green Thai sticks joints, drank good wine, loved to sing and laugh but at the same time we were serious players with a good dose of spirituality, in quest of understanding: working on our awareness, ethics and inner-growth. There was Yoga, meditation, travels to India, rebirthing, having babies naturally, and of course there was Ronnie, bigger than life itself.

But I would never be attending one of those heyday parties again. It was the end of an era. Jutta and Ronnie’s marriage was over.

Hanja Kochansky

http://gizmofilms.com/home-2-2/features/

https://www.amazon.com/Mad-Normal-Conversations-R-Laing/dp/1911383078